![]() 14ymedio, Reinaldo Escober, Havana, 15 May 2017 — On 11 May a new law went into effect in Cuba that imposes a determined price on the buying and selling of housing. The simple announcement, a month earlier, set off a frenzy in the notary offices to complete the paperwork for pending sales before the new rules went into effect. Some classified ads even included the date as the deadline to close the deal.

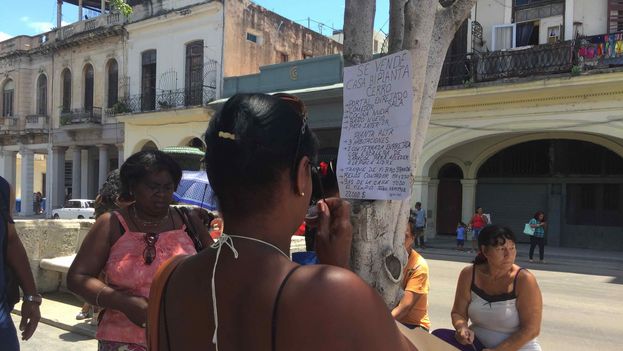

14ymedio, Reinaldo Escober, Havana, 15 May 2017 — On 11 May a new law went into effect in Cuba that imposes a determined price on the buying and selling of housing. The simple announcement, a month earlier, set off a frenzy in the notary offices to complete the paperwork for pending sales before the new rules went into effect. Some classified ads even included the date as the deadline to close the deal.

Since November 2011, when Raul Castro’s government allowed citizens the right to buy and sell their homes, an obligation was imposed on both buyers and sellers to pay the state a tax of 4% on the transaction.

In most cases, this levy was not calculated on the amount of money actually paid for the property, but on the basis of the price that the state had assigned to the home, which is recorded in the property document.

The Fiction

The Housing Act of July 1985 converted all tenants who were renting into owners. The value of the properties they took possession of was calculated by multiplying one month’s rent by 240, the number of months in 20 years.

Those who acquired a house as of from July 1 of that year, without making any up front payment, paid the bank, within 20 years, the price of their new house, which was calculated taking into account the square meters of living space.

It does not occur to anyone to sell for 10,000 CUP a house for which they can ask 30,000 CUC (that is 75 times more money), much less to refer to the real price when they can take advantage of the price shown on the initial title when paying the taxes.

In the cases of those who had paid rent before 1 July 1985, it is very difficult to find a home whose price as stated in the property title exceeds 10,000 Cuban pesos (about $400 US), because as a rule the monthly rent did not exceed 10% of the renter’s salary, and at that time almost no one earned more than 400 Cuban pesos (CUP) a month. And the values, calculated based on square meters, almost never reached 20,000 CUP.

That law, which boasted that it converted leasers into owners, did not allow the newly created owners to sell the property, so the prices inscribed on the title were evidence of the “character of fairness of the Revolution,” in giving the most humble workers the opportunity to legally posses a home. To put it in the language of the time, this was a “political matter.”

The Reality

At the time the right to buy and sell houses was granted, the consequences of the country’s system of two currencies – Cuban convertible pesos and Cuban pesos – were already in place. The most notable feature of this system is that workers are paid in the “national currency” – Cuban pesos – but almost everything that has real value must be bought in “hard currency” – Cuban convertible pesos, each of which is worth 25 times a Cuban peso. Housing did not escape this rule.

That evidence of fairness, reflected with a symbolic number in the property titles, could not be brutally reversed by the Revolution. But when citizens become cunning, the state cannot play the fool.

It does not occur to anyone to sell for 10,000 CUP a house for which they can ask 30,000 CUC (that is 75 times more money), much less to refer to the real price when they can take advantage of the price shown on the initial title when paying the taxes. That evidence of fairness, reflected with a symbolic number in the property titles, could not be brutally reversed by the Revolution. But when citizens become cunning, the state cannot play the fool.

This is how the new “reference prices” came about.

The new methodology does not take into consideration how many years of salary a worker must invest to pay the new prices and also does not indicate the square meters of living space. Now the value of a housing unit is calculated by a set of factors. Among these is the number of rooms and whether it has parking, patios or gardens. The construction characteristics of the homes are identified depending on whether they have masonry walls, heavy or light roofs, or if they have been constructed with other materials.

And the most significant factor is where the property is located. There are five groups and each corresponds to a “location coefficient,” where the word coefficient has the meaning given by mathematicians to a multiplicative factor. Therefore, once the housing value is established, the resulting number is multiplied by 7, 6, 5, 4, or 1.5 depending on where the home is located.

This onerous multiplication is not accompanied by revolutionary slogans or theoretical considerations about social justice.

Obviously, the state does not care what anyone spends to buy a house, but it does care how much it can raise through that 4% tax on the reference value.

Paternalism is over. That time when a local assembly (a political entity) assigned a home to worker based on his or her “social virtue” and “labor merits” is a thing of the past. The state no longer gives, it only takes away. Consequently, the citizen no longer feels that he must surrender, but rather he must defend himself. That seems to be the signal of the new times.