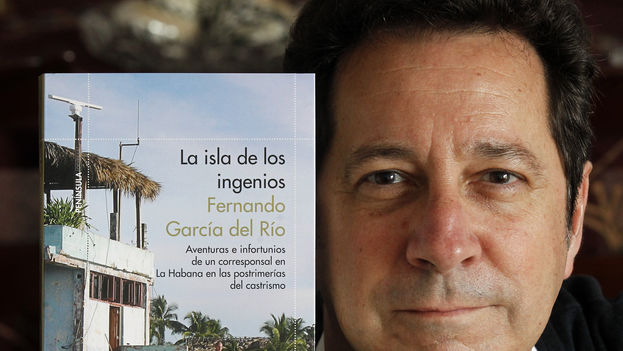

14ymedio, Yoani Sanchez, 6 April 2015 — Fernando Garcia del Rio was a correspondent in Cuba for the Spanish newspaper La Vanguardia (Barcelona), from 2007 until his expulsion from Cuba in 2011. He has just published a book,“The Island of the Mills,” where he relates the “adventures and misfortunes of a correspondent in Havana in the final years of the Castro regime.” From Madrid, where he still works for La Vanguardia, the author has responded by email to questions from 14ymedio.

Question. Why did they expel you?

Response. It is obvious that my work did not please the authorities. They did not specify the reasons in detail. One day in March 2011, when I was about to complete four years as a correspondent, an official from the International Press Center (CPI) called me to a meeting the following Saturday morning. For more than a year that organization had let me waiting for the renewal of my accreditation, an essential document to be able to work on the island. I’d also spent some months without receiving any calls or communication from the CPI. And this, as a member of that body explained to me with obvious cynicism, meant that I was in a phase that implied, among other things, “the silence of the mails.” continue reading

The fact is, that at the final meeting at the Center’s site on the Rampa, the official in charge of communicating to me the outcome of the process sat across from me and limited himself to reading what he had brought written on a piece of paper. It was Article 46 of the CPI rules, according to which the entity can withdraw a correspondent’s accreditation when it considers that there has been a lack of ethics or objectivity, or actions “inappropriate” to the mission. I asked how and in what reports had I incurred these suspicions. The official, instead of answering me, unfolded the paper again and repeated to me the contents of the article in question. He did answer my question regarding if there was a timeframe for me to leave, “As soon as possible, as soon as you organize the move and sell your car,” he said.

“I’ve often wondered which article or articles could have bothered them so much. The one I devoted to the significant drop in the rates of Communist Party memberships?”

In the book I tell the story in detail, but not without noting that the CPI expelled a ton of journalists in similar circumstances. So the event was nothing extraordinary, although telling the story is still illustrative. I’ve often wondered which article or articles could have bothered them so much. The one I devoted to the significant drop in the rates of Communist Party memberships, and how much this fall worried its leadership. Or maybe it was the report about the terribly poor sugar harvests of 2010 and 2011, titled, “Cuba’s bitter sugar”?

Question: It has been four years since your expulsion. Does Cuba remain in your dreams and nightmares?

Answer: Of course it continues in my thoughts and in my memory. Predominantly fond memories. Cuba is a unique and unforgettable country. For starters, coming from outside can feel like a time machine. Or like being in a period film – back to the fifties – where contemporary elements seem like mistakes in the props. That feeds the reverie. Beyond this imaginary sensation there is maybe something superficial, I see Cuba as a country with people hungry for the future who improvise the present minute-by-minute within a system anchored by the past. A broken country, in a material and figurative sense, as so many of its buildings and its streets are broken, but also its economy, communication with the exterior, and the families who remain separated by a stretch of ocean. But Cubans masterfully use an infallible weapon against the breakdown of hope, which is resourcefulness.

The [Spanish] Real Academia dictionary gives this term three principal meanings, as well as one relative to sugar factories. Ingenuity is the “ability of man to devise or invent quickly and easily”; it is also “industry, cunning and artifice of someone to get what they want,” and at the same time, “the spark or talent to rapidly see and display the funny side of things.” I believe that it is thanks to ingenuity, in its different forms, that most Cubans continue to get ahead. With ingenuity to fix the broken and fill the vacuum; to stop and confuse the adversary with humor and constructive spirit. Hence the title of the book, clearly.

Question: How difficult was it to practice journalism onThe Island of the Ingenuous?

Answer: What can I tell you about that?! Of course, the difficulties aren’t the same for a foreign correspondent in Havana – at the end of the day, a kind of passage through the country with someone having your back – than for a Cuban journalist who puts it all on the line. So, I send my respect and sincere admiration to my colleagues on the Island who, against all odds, try to do real journalism inside the country. That said, in my case as a correspondent, the main and most obvious difficulty was maintaining an acceptable balance between a commitment to the readers for the truth and the desire to keep one’s position; that is, to relate events without hiding the essential data but without getting the country’s authorities all stirred up.

“As a correspondent, the main and most obvious difficulty was maintaining an acceptable balance between a commitment to the readers for the truth and the desire to keep one’s position”

On the other hand, in Cuba informative material is peculiar. More than news, what you find are propaganda and rumors. But beyond what circulates in the media and is put at your disposal, the field is enormous. Regardless of the political decisions, the relevant announcements and the more or less substantial official discourse, Cuba seemed to me from the beginning a country that deserves to be told. Because, given that everyone has to invent a life for themselves every morning, things are constantly happening to all Cubans.

So the stories are endless, and almost always interesting because they speak of the daily bread. It’s not about “objective conditions,” figures on the “blockade” or other aspects of the everlasting conflict with the enemy; it’s about raw reality, which is what should come first to us journalists. Reality with a face and eyes, although at times you have to hide identities to avoid problems with the staff. And if, in addition to this reality, you tell it gracefully… Finally, sometimes the system serves you gems, involuntarily, real jewels for the daily chronicle. I’m referring to the reports that Granma or Juventud Rebelde publish from time to time, intending to counter something or meant as a warning, but that for the foreign media are like diamonds in the rough.

I remember discovering an “urbanization” of 350 houses made with railroad rails and sleepers in a coastal neighborhood called La Panchita. The residents, beset by the severe housing shortage suffered by the entire Island, pulled up 15 miles of railroad track to get the construction materials they needed to build their homes. The government published this finding with great scandal and indignation and with the announcement of disciplinary measures. They had to show that in Cuba people are made to pay for their crimes. Meanwhile, what this gave me was excellent raw material for an article on the housing shortage, and the theft of materials as a recourse to alleviate basic needs.

Question: Ingenuity, creativity, “resolve”, “under the table”, “invent” … many different ways of calling the juggling of survival we have to perform every day. Did some of them have a lasting impact on you?

Answer: In my book I dedicate a chapter to the “resurrection of scrap.” Here I report my discovery of what Cubans think is a total classic. I’m referring to the use of the Russian Aurika 70 washing machine for purposes that have nothing to do with the original. I discovered it in a casa particular [private B&B] in Viñales. The owner – his wife told us – couldn’t come out to greet us because he was enjoying a “hydromassage session.”

We went through to look at the courtyard of the house and the guy had his hand in the washing machine. He explained how this had been prescribed by his doctor: he should put his hand in there for 20 minutes a day, I think on the prewash setting, for his injured wrist. Then the man showed us the fan he’d hooked up with the motor from the drier. Later I learned that this was a more or less usual practice, with this and other appliances distributed by the State, and that, being so widespread, it had even set off a national debate about the supposed energy waste.

“The architects of Old Havana say the ruined or semi-ruined buildings still standing in defiance of the laws of physics are ‘in miraculous static.’ The image is useful to describe the lives of most Cubans”

They told me that the Aurika was also a stupendous tomato crusher. I learned of the electric teakettle converted into a shower heater, the rikimbili (a bicycle converted into a motorcycle), and I don’t know how many more inventions. But it not only made me admire the ability of Cubans when it comes to making utensils from almost any object; as much or more I admired your infinite capacity to fabricate metaphors. It sticks with me, the expression created by the architects of Old Havana to classify ruined or semi-ruined buildings that are still standing, year after year, in apparent defiance of the laws of physics: they are building, they say, “in miraculous static.” In addition to being a poetic and humorous definition, the image is useful to describe the lives of most Cubans. In any event, it’s great.

Question: Last December 17th the restoration of relations between Cuba and the United States was announced. Was this something predictable in the years you lived in Havana?

Answer: No, I didn’t imagine it. Some American officials and academics with good connections to the White House pointed out, then, that Obama could take important steps to approach Havana in his second term, that is, now. But neither I nor the European journalists and diplomats whom I know thought there would be such a warm agreement after 54 years of rupture. I suppose that the process towards full normalization will be slow and not free of surprises. Hopefully, those interested in stopping it will fail this time.