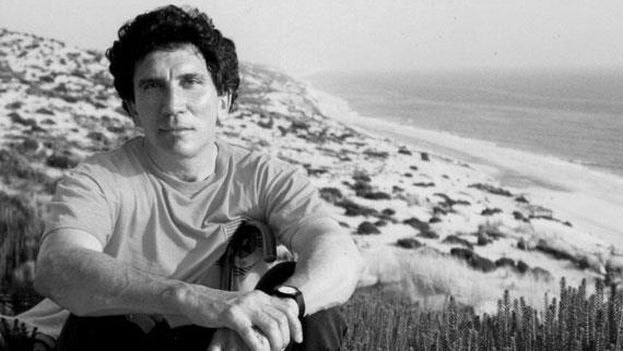

![]() 14ymedio, Xavier Carbonell, Salamanca, 15 March 2023 – In the film The Lives of Others, the writer Georg Dreyman encapsulates his break with the regime in a report about suicides in communist countries. He writes it in red ink on a secret typewriter and under the vigilance of secret agent Wiesler, alias HGW XX/7. When I had just finished reading The Secret Island, by Abraham Jiménez Enoa (born in Havana in 1988), it seemed to me to be the reverse kind of book — almost tropical, although no less dramatic or oppressive.

14ymedio, Xavier Carbonell, Salamanca, 15 March 2023 – In the film The Lives of Others, the writer Georg Dreyman encapsulates his break with the regime in a report about suicides in communist countries. He writes it in red ink on a secret typewriter and under the vigilance of secret agent Wiesler, alias HGW XX/7. When I had just finished reading The Secret Island, by Abraham Jiménez Enoa (born in Havana in 1988), it seemed to me to be the reverse kind of book — almost tropical, although no less dramatic or oppressive.

The book doesn’t hide its scars. It talks of a nervous people, hungry, people who want to escape or kill themselves. Every page was written as the polar opposite of the official tourist guide to Cuba. It is important that a book like this is published in Europe, where some newspapers are still promoting the Island as a paradise of communist nostalgia, with cheap hotels, cigars and mulatas.

Jiménez Enoa goes further even, than just describing the “real and the incredible” poverty of Havana, ‘invention of foreign correspondents’. His interviewees, who come from a wide variety of provinces and dangerous neighbourhoods, live for la bolita — a lottery-type betting game prohibited by Castro — and they cure their illnesses using only water; they have two religions (“yoruba culture and football [soccer]”); they build portable houses out of cardboard and go out chasing French or Italian women, “the uglier and fatter the better, because those are the ones who need affection the most”. continue reading

Up until half way through the book the stories are pretty harmless. He goes out in search of the unusual but stops short of crossing the line into risky political areas. This is the natural condition of the independent journalists in Cuba — they are the marginalised, stuck in their tribe. But from this point on, things begin to change in the book, the voices move forward, and the language — earlier, varied and ambiguous — becomes a machete blow. Whereas before he used the word ’government’, now it becomes ’dictatorship’; where before he spoke of anonymous swindlers, later he alludes to the imprisoned artist Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara or to the dissident Ariel Ruiz Urquiola. He directly questions the president and the generals, describes his “walks” around Villa Marista, the general headquarters of the State Security secret police. Now he has nothing more to lose.

Jiménez Enoa’s works have a strange predilection for the law. With some well calculated pauses between paragraphs he points out which article of the Penal Code his interviewee is violating, and how to use this fact to challenge the police. He has read between the lines of the constitution, of Castro’s speeches, and even of the threats made by the torturers. Everything has a legislative or authoritative value, everything practiced in Cuba is criminal and if there’s a cover-up it is there once again in the language: to resolve, means to steal.

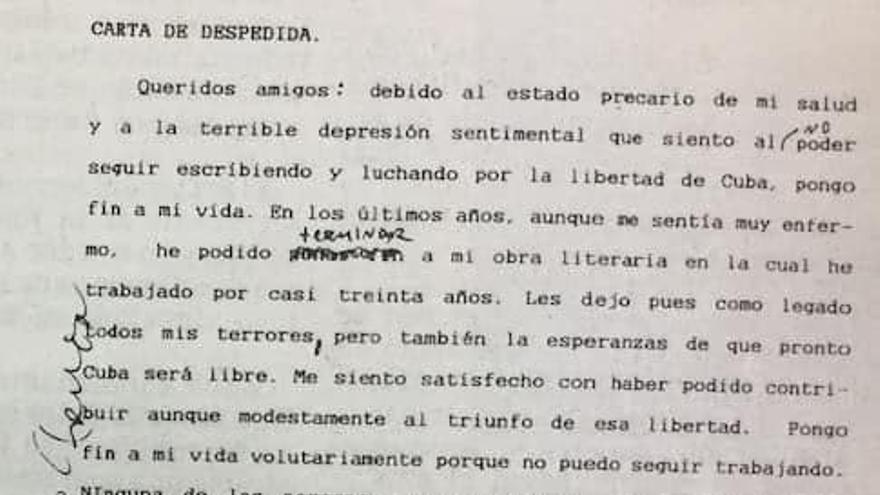

Money is another obsession in the book. How does one manage to eat or to live in a country where wages are not enough to cover the basics. A gigolo gives him the key: in real life “there are no tariffs, only cushy jobs”. He fights against everyone and against history like those people who built their ramshackle huts on the edge of Che Guevara’s mortuary square in Santa Clara, visited by tourists and government leaders. It’s the tension between the desire to live and the ghost of Castro and his guerillas. But if you can’t escape from the country, there’s always a metaphysical escape: suicide.

Whilst reading The Secret Island, another force becomes apparent, one which doesn’t often show its face and which couldn’t be more decisive: the battalion of spies, confidantes, patrol cars, informers and sympathisers of the regime. One can fight against them up to a certain point but their skill lies in their persistence and in their talent for destroying lives. In a final self-portrait, Jiménez Enoa offers up the creed of an escapologist from time and space: “Escaping from Cuba is not the same thing as escaping from any other country for the first time. To escape from Cuba is to fall into the world, to realize that Cuba is an island that has been hijacked by a political system which ensures that the country remains locked inside the twentieth century”.

I suppose that Jiménez Enoa will ask himself the same question as all of the other artists and intellectuals who have become exiled from Cuba in recent months: After his book-exorcism, his testament-report, his page-frontier, what next? Hopefully not too many years will pass before he’ll be able to dedicate a ’Sonata for a good man’ to those who watched over him, like the one that Dreyman wrote for HGW XX/7.

Exile, as the only way out

As a result of his publication, Jiménez Enoa was arrested, interrogated, tortured, and finally regulado [regulated], a method used by the Castristas by which a citizen is prevented from leaving the country freely. After he did finally escape however, and was living in a place as peaceful as Amsterdam, one of the regime’s agents actually turned up at one of his conferences and aggressively shouted out at him like a maniac that everything he was saying was a lie.

____________

Publisher’s note: This article was first published by the Spanish daily El Mundo, in their cultural magazine La Lectura.

Translated by Ricardo Recluso

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.