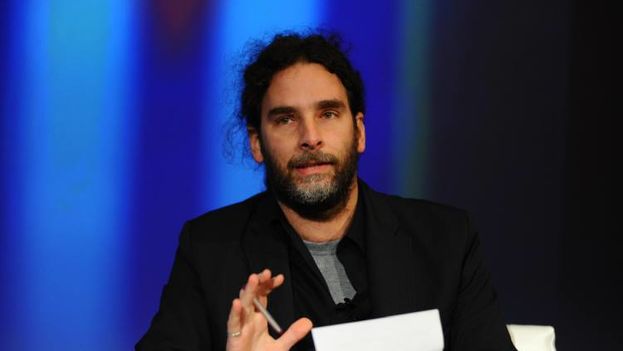

![]() 14ymedio, Luz Escobar, 10 January 2016 – A Cuban jaded in the cynicism of the present travels back in time to the year 1960 searching for the lost epic. The story of someone who wants to regain the enthusiasm around a social project that turned into something very different from the dream, will move and amuse those who see the latest short film directed by Eduardo del Llano.

14ymedio, Luz Escobar, 10 January 2016 – A Cuban jaded in the cynicism of the present travels back in time to the year 1960 searching for the lost epic. The story of someone who wants to regain the enthusiasm around a social project that turned into something very different from the dream, will move and amuse those who see the latest short film directed by Eduardo del Llano.

Epic is a touching portrait of some people’s disappointment and others’ Utopia, blending the absurd, science fiction and drama. Its director, scriptwriter and principal architect talks with 14ymedio about his latest film “creature” and other demons of filmmaking.

Escobar. With your latest short film Epic are you returning to science fiction?

Del Llano. In Epic science fiction is like an anomalous element that allows me to make contact between a Cuban of today and another from the sixties. This latter is also a Cuban who is real and very important in Cuban culture, a Cuban who existed just at that moment when everything was epic, when everyone believed in the Utopia, and it seemed like everything would turn out well. The expectations generated in contrasting the Utopia with the actual result, obviously would have been impossible in a strictly realistic narrative. continue reading

The idea was to be able to present, with a more or less logical premise – one that allows the viewer to suspend disbelief – a Cuban of the present and another from the past, both situated on the two extremes of the chain, not the food chain but the utopian ideological chain.

Escobar. Epic was presented at the last Havana Film Festival. Will it go into regular screenings in the coming months?

Del Llano. I don’t know if will be scheduled, but I don’t much care. For me, it was very important that it was shown in the last Festival, although they gave me the worst possible times. At the Chaplin Theater, on a Sunday at ten in the morning, and, even worse than that, at the Infanta multiplex on Saturday at half an hour past midnight. Even I didn’t go there…

Escobar. How did the audience react?

Del Llano. People had a kind of catharsis. When it ended they clapped and even shouted “Bravo!”

Escobar. Surely this short will circulate in the weekly packet. How do you deal with piracy?

Del Llano. It has been a problem. I think I know pretty well how to make a movie up to the moment it ends, but I don’t have the slightest idea what to do with it then. Internally, I have no problems with the packet, I think it’s the Cuban equivalent of any broadcaster in the world. Where there is everything from the most ridiculous like Case Closed, to the highest quality Scandinavia cinema.

Escobar. Sex Machine Productions is a pioneer among independent producers. How has it managed to survive despite having no legal recognition?

Del Llano. Sex Machine Productions was a gentleman’s agreement between Frank Delgado, Luis Alberto Garcia and Nestor Jimenez. We agreed that we would do things like this as a cooperative, where I pay what I can and if at some point we hit it big and earn a lot of money, it will be distributed based on determined percentages that we adjust at that time, but it is not a producer in and of itself.

Sex Machine Productions is me. There are shorts where the character of Nicanor* does not appear, nor is there Frank’s music, nor do Luis Alberto or Nestor act in it, but it comes out under the same logo.

Escobar. You have feature films and many shorts. In what format do you feel more comfortable?

Del Llano. At one time I said that would only make shorts, not out of conviction, but because I felt comfortable with the shorts. Even my two feature films are not very long, one is 61 minutes and the other 73 minutes.

Escobar. What genre do you prefer?

Del Llano. I always thought – and I’m paying for it firsthand – that in Cuban cinema we should have science fiction, terror, erotica. I took the risk and now I’m coming up against the idea that, “and now this movie doesn’t seem Cuban because there are no prostitutes and no salsa music.”

Escobar. Are you a part of the group of filmmakers that is promoting a new Film Law, the so-called G-20 group?

Del Llano. There are a lot of misconceptions about what the G-20 is. We are a gathering of filmmakers where there are no directors, no art directors, no photography directors, and we meet as if as we are going to put fifty or sixty people to the task of writing a text, we choose a kind a “central committee” so there is an executive arm.

If at a meeting there is an agreement to draft a document, they are responsible for writing it. This is the G-20, but it is not “20 filmmakers fighting for a Film Law in Cuba,” because we are much more than that. Nor are we always the same people, although there are faces that remain, out of respect and visibility, which is the case with Fernando Perez.

Escobar. What have you achieved with your demands?

Del Llano. From the beginning we have tried to work with what is established, because it is about a law, not about a revolt. We have tried to fit it into the legislation that already exists, but also to start expanding it. At the first meetings there were representatives from the Ministry of Culture, I don’t know if there was also anyone from the Cuban Writers and Artists Union (UNEAC), but they don’t come anymore. I feel like they are waiting for us to get tired.

The October meeting last year ended with the adoption of a draft Film Law. The ball is now in their court.

Escobar. And so what’s missing?

Del Llano. What’s missing is someone who comes along and says, “this isn’t the way to do this and this”… to see it through the eyes of the censor, of the other side. In this sense we are a little stagnant, which doesn’t mean we are going to give up. We are not going to stop insisting, but we see no response.

Escobar. The last meeting was fraught with tension…

Del Llano. Hopefully not, but I suspect that the last meeting where the incident occurred with Eliecer Avila, they are going to use that to say, “See what happens when you meet,” and then throw some more shit on is. I Am not aware that it is going to be like this, but I suspect it.

The same attitude of ejecting someone from a gathering because they are considered “counterrevolutionary” is as if they were some Saint Benedict that you can’t get rid of, as if they were synonymous with a provocateur. Eliecer was sitting behind me and remained silent the whole time. Even when the issue came up of throwing him out.

Then, indeed, ICACI and UNEAC appeared saying, “we are revolutionary filmmakers.” So they did respond to this. What worries me is that the ICAIC, which the whole time has said it is on our side, reacted with this level of intolerance against someone who thinks differently.

Escobar. What projects are you working on?

Del Llano. What I have in hand are fake documentaries. I really like this format that few in Cuba have done. I did The Truth About G2 [Cuba’s State intelligence service], and the things that I have in mind come from that. For example, I published a novel last year and when Luis Alberto Garcia read it he said to me, “We have to make this novel into a movie.” For now it would be hard to do that because it requires an enormous budget.

It is titled Bonsai and is about a town in Pinar del Rio which is isolated from the rest of Cuba and there they build communism, but by chance. Even the things they do they don’t do well, but it comes out fine, thanks to chance. They construct a viable communism, with freedom, with democracy, with positive economic results, like it should have been, where everyone in the world does well.

I would love to film that story.

*Translator’s note: Nicanor O’Donnell, played by Luis Alberto Garcia, is the “anti-hero” character in several of Del Llano’s films. Read more here. The films are on YouTube, in Spanish