The mambises forces couldn’t recover from the uprising at Santa Rita. Insubordination and desertions were frequent. Dissatisfaction and fatigue had taken over the troops. The territories held by the Cubans were wastelands. General Martínez Campos took advantage of these circumstances and launched a successful offensive against the central territory. There were nonetheless numerous officers and soldiers who rejected the uprising, but the policy of Martínez Campos of reinserting those who presented themselves contributed to the undermining of unit morale, this together with the military harassment of the rebels.

The designation of Vicente García as President of the rebel republic caused widespread disgust. Máximo Gómez’ resignation as Secretary of War was accepted. It was December of 1877, a year that Gómez would call the most ill-fated for the Cuban revolution. Gómez proposed a cessation of hostilities under the pretext of consulting the people, using the opportunity to reorganize. Under these circumstances the negotiations began that would culminate in the Pact of Zanjón. In compliance with the naming of Vicente García as President, he formed up his unit for consultation; those who were in favor of peace should stay in their places, those in favor of war should drop out of the formation. Nobody moved. Only two among the leaders and officers voted differently than the troops. The chamber dissolved itself and named seven commissioners to adjust the peace terms that would be worked out on February 10, 1878.

These few lines cannot contain the contradictory feelings of those men who through so many years fighting for independence, at the end, didn’t get it. I wouldn’t dare to use the term zanjoneros as a synonym for traitors as has been done in recent political propaganda.

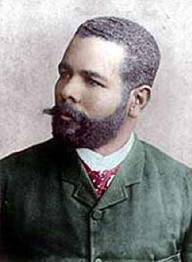

Antonio Maceo had achieved important victories against Spanish convoys in the eastern region during the month of January, and in that same month the Chamber of Camagüey promoted him to Major General. His unit having nothing to do with the uprising of Santa Rita, and with high morale, the Pact of Zanjón, ending the war, surprised him. Máximo Gómez visited him on February 18th to say goodbye and left him with the situation in Camagüey and the Center. On the 21st, Maceo asked Martínez Campos for a suspension of hostilities for four months to consult his leaders and to let the Spanish general understand the benefits of a peace without independence, and they agreed to meet on March 15th.

The Protest of Baraguá is one of the best known episodes of the Ten Years’ War, all Cuban children can repeat the verse of the corojo roto; but not many know what happened after the historic protest. That very same night in the rebel encampment, the continuation of hostilities was declared, with Vicente García as General-in-Chief and Maceo in command of Oriente. The attitude of the Spanish troops, who responded to rebel fire with cheers, sowed confusion in the unit. Meanwhile, Martínez Campos was preparing a formidable force with which to pounce on Oriente. The attitude of the Spanish troops was of absolute respect and chivalry. Isolated and bloody fighting broke out, but Maceo didn’t return to fight. The representatives who emigrated had surrendered, no help materialized from abroad, and the situation threatened to strangle the independentistas with the Spanish offensive on one side and the lack of resources on the other. It was necessary to salvage what was possible, and Maceo obeyed the decision of the Government to flee to Jamaica. It was his plan to reorganize the fight, but after his experience in Jamaica, he wrote from New York to the Government begging it to avoid useless sacrifices. The war officially ended barely two months following Baraguá.

Differently from Gómez and from Maceo, Vicente García demanded a quantity of gold from the Spanish authorities for his surrender and payment in the same manner for his ranch with 150 heads of horses. The decision to endow each province with its patriot turned him into the hero of Las Tunas. In real history, his worst indiscretions are treated with delicacy, being as he is one of the principals responsible for the regionalism and caudillismo that lost the war.

Other less-well known mambises, like Limbano Sánchez and Ramón Leocadio Bonachea didn’t accept the end of the war and continued fighting until later incorporating themselves into the Little War.

March 16 2011