Four days before Oswaldo Payá was killed, I drove past the exact spot where his rented blue Hyundai slammed into a tree.

I didn’t find out about the crash until I was en route to Florida on July 22. I had known Payá for many years and was saddened to hear of his death.

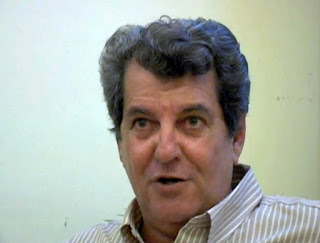

Quiet and determined, Payá was unlike most Cuban dissidents I have met. Most lose their government jobs soon after they declare opposition to the socialist state. Payá kept his as a medical equipment specialist.

Another thing that distinguished Payá is that he tried to change the Cuban government from within rather than tear it apart and start over. He recognized that the Cuban constitution allowed citizens to propose changes as long as they collected 10,000 signatures. So in 1998 he launched the Varela Project, a petition drive aimed at bringing about democratic reforms.

“We reject all violence, offensive language, intolerance, terrorism…” Payá said.

Payá was a spiritual man, a devout Catholic. That much was clear when I met him at his home in Havana in 1998. A portrait of Jesus hung on the wall. Pope John Paul II was scheduled to arrive in the country days later.

Payá, then 45, was president of Christian Liberation Movement, a 300-member civic group. He said all Cubans – including those in the U.S. – should forget their differences and work toward rebuilding Cuba.

“No more hate among Cubans,” he said. “No more blood.”

Some hardline Cuban exiles in Miami opposed Payá’s efforts. They said working within the socialist system was useless, and only a more aggressive approach would dislodge Fidel Castro.

Payá also faced criticism – and persecution – in Cuba. He said state security agents ransacked his home in 1991 and scrawled slogans on his walls: “Payá – an agent of the CIA” and “Long live Fidel!” And security agents visited his workplace so often “they almost seem like family.”

“We don’t lead a normal life,” he told me in 1998. “I sometimes live in fear. But God gives me the strength to go on.”

During our interview, Payá complained bitterly about the lack of basic freedom in Cuba.

“Right now, the system controls everything: buying, selling, having, expressing yourself. It’s a form of modern slavery.”

He also expressed optimism.

“Cuba has started to change in a fundamental way, in peoples’ hearts.”

After the pope’s visit, some of that optimism seemed to fade.

“Change in Cuba will happen only if Cubans want to make it happen,” Payá told me after John Paul II left. “The mere presence of the pope wasn’t enough.”

The years went by and Payá continued plugging away on the Varela Project.

By May 2002, he and his followers had collected more than 11,000 signatures and turned them over to Cuba’s National Assembly.

Word of the Varela Project spread. Then-President George W. Bush endorsed the initiative, named for Felix Varela, a Roman Catholic priest and Cuban independence hero. And when former President Jimmy Carter visited Cuba, he met with Payá and mentioned his project in a nationally televised address, marking the first time many Cubans had heard of it.

Shortly afterward, Payá spoke to reporters outside the Hotel Santa Isabel. Payá called Carter “a man of dialogue and a man who builds bridges.”

Cuban officials, meantime, hadn’t put any of Payá’s proposals before the National Assembly, despite the signatures.

Instead, they answered with a campaign of their own in June 2002. They held, by their count, 845 marches and 2,330 rallies aimed at showing support for the Cuban government and opposition to U.S. policy.

They said 9 million of the country’s 11 million people took part, including Fidel Castro, then 75, who wore tennis shoes as he marched past the U.S. Interests Section.

“If government leaders have so much support,” Payá said in response, “why not do a referendum on the Varela Project? What are they afraid of?”

Castro supporters weren’t done. They also organized a petition drive to change the constitution, making socialism “untouchable.”

One diplomat I spoke to called it “overkill.”

Payá said, “It’s a technical coup d’état.”

I saw the dissident leader again in February 2003. Then 50, he told reporters that the Varela Project had thousands of supporters.

“It’s a campaign and it’s going to continue,” he said. “Millions of Cubans are demanding their rights. Support that has never been seen before has been awakened.”

He acknowledged that he could be jailed at any time.

“For any dissident, the possibility of prison is always there, every day and every hour,” he said.

By then, Fidel Castro had finally commented on the Varela Project, calling it “foolishness.” But Cuban authorities evidently took it seriously because in March 2003 they arrested 75 dissidents, including more than 40 who worked on the project.

Payá wasn’t arrested. His international acclaim, it seems, saved him. And he continued collecting signatures.

“Hope is reborn,” he said in October 2003, reading from a statement. “Hope is reborn because we have the determination to continue this campaign for the rights of all Cubans… And we know victory will be that of the people.”

In reality, the Varela Project didn’t achieve the changes that Payá had sought. But he never gave up trying to bring about peaceful change in Cuba.

I caught up with Payá again in July 2010 while working on an investigative project that I have been doing with support of the Washington, D.C.-based Pulitzer Center.

Payá and his wife, Ofelia Acevedo, lived in the same house in Havana’s El Cerro neighborhood. I asked Payá how things were going. He complained that state security agents followed him when he traveled. Just a few days earlier, he said they had tried to convince a driver to drop him off in the middle of nowhere while taking him back to Havana from the town of Cienfuegos.

“The driver refused to drop me off,” Payá said.

He didn’t expect the harassment to end anytime soon.

“State security restricts, persecutes, expels many dissidents from work, their family members, too,” he said. “And then many people are scandalized because some in the U.S. and around the world want to send aid to dissidents.”

I asked him about U.S. government financial support for Cuban dissidents.

“That’s not going to dictate change,” Payá said, “but nor should it be an excuse for failing to recognize the essence of the problem. And the essence of the problem is that the Cuban government does not recognize the rights of Cuban citizens in Cuba. And that’s called tyranny, that is oppression and that causes many Cubans to suffer.”

Unfortunately, Payá said, most Cubans are poor, they have few options and “do not have a vision of their future in Cuba.”

“Therefore they want to leave the country. So the problem is in Cuba, and the solution is in Cuba and among Cubans,” he said.

Two years after our interview, I was in Cuba again. This time around, I went to Santiago de Cuba and met with dissidents, among many others.

The next day, while driving toward Havana, I passed the spot where Payá’s car would crash four days later.

The highway at that point quickly deteriorates into a gravel road. I expected Cuba’s main east-west thoroughfare to be bigger and wider, but it’s a narrow, two-lane country road carrying everything from farm equipment and old Russian trucks to semi-trailer tractors and rental cars.

Everyone moves along at dramatically different speeds. I saw decades-old American cars weave around horse carts that were passing bicyclists, filling both lanes of traffic. I even spotted a woman pushing a baby carriage on the highway.

Payá and another activist, Harold Cepero, met their fate along the same stretch of road. May they rest in peace.

Note: This article was written in Spanish and English by Tracey Eaton who blogs at Along the Malecon. It is the first of the articles from Voices Magazine No. 16, published in Havana on Friday, September 7, as a tribute to Oswaldo Paya. Translating Cuba will attempt to bring our readers the entire issue in English.