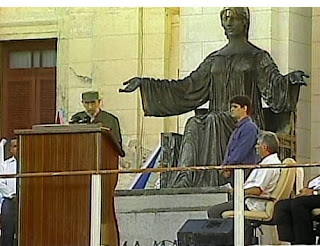

Photo: Penultimos Dias

I’ve made quite an effort not to write about Fidel Castro. First, because I’m not capable of saying anything serious about his persona (sometimes I would like to take him less lightly); second, because reading his “Reflections” has the same affect on me as do some science fiction fanzines (I like the genre), and third, because the Commander-in-Chief is today, despite himself, a ghost from the past of Cuban politics.

But he won’t stop talking! He publishes books, predicts the future of the human race, speaks about himself, confuses José Martí with Lenin, changes the past, annuls the future, and has a temper tantrum in the present because he is running out of time. He continues to appear over and over in scenes more like the theater of the absurd than the desperate politics of a system in ruins. Whether at the aquarium, or at a special session of the National Assembly, the costumes are worn at the seams, but the piece is played as if elegantly staged. Always surrounded by bodyguards (we call them “avatars” for their physical appearance), the old man doesn’t fall down but slips through the recesses of his mind, destroyed by power. After so many years enjoying the life of a Messiah, it is impossible for Fidel Castro to now assume that his death will not change the course of history, that the Year Zero will not be repeated, that Cuba will continue on its path and that his brother will or will not make some changes when he no longer exists (before himself being absorbed by the Change once he’s left alone). He has written his apocalyptic script like a prelude to departure. He will not take us with him because he can’t, but until the last instant of his earthly existence he will assign roles, cut off heads, vilify his enemies and announce — through some kind of amazing theory — the end of the world. He will die, but not before trying to make us believe that all of humanity is going with him into the grave.

Isolated from everything, his reality has become a mirror of a future where his image is not included. It no longer matters that the history of the Cold War is a rotting corpse that will never be revived. His only option is to construct a scene where he is not the premonition of his own illness, but rather the illness of the rest of us: nuclear war as a palliative of the mortality of a single human being. Whether well constructed or not, fear and opportunism will do the dirty work. Each one of the actors in his staged scenes follows his script exactly, from asking the entire Cuban art world to reproduce the Cuban Five, to requesting, tearfully, to be allowed to kiss the Commander.

In the government they’re pulling their hair out trying to prevent the economy from a near-term collapse, the power is rearranging itself, and corruption is becoming the new face of island totalitarianism. Meanwhile, at the University of Havana Fidel Castro, looking for his own eternity on the earth that is going to swallow him, reminds us that “…the hard work of warning humanity of the real danger that it faces falls on Cuba, and in this effort we must not lose heart.” But the stage machinery of his act dissolves on the faces of this audience of bored twenty-somethings; they do not feel beholden, they long to leave the country by any door, and their memory of nuclear confrontation comes down to the movie “Lisanka.” Comrade Fidel faces a public that cares not a whit about his misunderstood mortality and his prediction of nuclear catastrophe, because the only bottomless thing about the University of Havana student body is their twenty years.

September 5, 2010