Since 1980, Cubans have celebrated 20 October as National Culture Day, in evocation of a local date of warrior exaltation, the triumphal entry of the small Bayamo Liberation Army, centered around the planter Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, who on 10 October 1868 gave freedom to the slaves of his sugar mill and proclaimed the beginning of the struggle for the independence of Cuba.

Since 1980, Cubans have celebrated 20 October as National Culture Day, in evocation of a local date of warrior exaltation, the triumphal entry of the small Bayamo Liberation Army, centered around the planter Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, who on 10 October 1868 gave freedom to the slaves of his sugar mill and proclaimed the beginning of the struggle for the independence of Cuba.

As the colonial regiment commanded by Julian Udaeta surrendered before the cheering citizens, supporters of independence, Céspedes and his followers celebrated the victory in the Plaza of the Parish Church with a ceremony and a festive conga for the people.

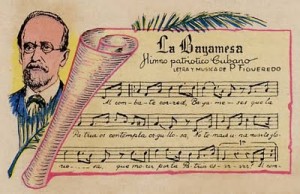

At that time, Pedro Figueredo Cisneros distributed the verses of The Bayamesa, whose music and lyrics he had composed in the previous year with the help of his wife, the poet Isabel Vazquez, upon request of the illustrious Francisco Maceo Osorio, who later was the assistant Carlos Manuel de Cespedes along with Figueredo.

It has been said that amid the euphoria, the creator and Bayamese patriot improvised lyrics about his horse to sing in chorus for the first time, but the testimonies of his contemporaries reveal that music and the verses were known by many conspirators who had kept silent for their own safety. Perucho, they called Peter Figueredo, played the score at home to dozens of trusted friends and entrusted the orchestration of the piece to the maestro Manuel Muñoz Cedeño, who first performed it publicly in the main parish on the occasion of Corpus Christi, in the presence of the priest Diego José Baptista and the aforementioned Julian Udaeta, military governor of Bayamo, which faulted the instrumentalists for the subversive nature of the march.

The Bayamo Anthem, played on 20 October 1868 and published on 22 and 27 of that month and year in The Free Cuban, embedded itself in the minds of the independence fighters, who often sang it in combat or to start sessions of the House of Representatives, a sort of parliament in the jungle.

Although José Martí praised what happened on that October 20, 1868 and reproduced in Patria the stanzas of the Bayamo Anthem, in June 1892, and on January 21 and October 4, 1893, it was the Constituent Assembly in November 1900 which declared it a national symbol.

In October we commemorate other historic ephemera, such as the discovery of America – 12 October 1492 – and the arrival of Christopher Columbus on our shores days later, an event of great significance for the encounters of peoples and cultures, and international mobility that erupted between Europe and the so-called West Indies.

More than a fact of cultural consequence, the evocations of October 10 and 20, 1868, signals the warrior affinity of those who rule the island like those Captain Generals appointed by the Spanish overlords until 1898.

The story gallops in the memory of the people, but does not model the culture, it complements it. We will have to rewrite the story of war, unilateral and simplistic, that creates myths and masks the oppression. Today, as in 1868, the stanzas of the Bayamo Anthem, turned into the National Anthem, represent a dilemma of our reality, but no one calls to combat nor thinks about guns. Is it that we fear a “glorious death” or that we have gotten used to “living with shame and ignominy”?

Translator’s Addition:

October 13, 2010