In the TV program “Round Table” on Thursday, October 18, Teresa Amarelle Boué, a History and Social Science graduate and Secretary General of the Federation of Cuban Women,more or less said that, thanks to the 1959 revolution, Cuban women had gained the right to vote. Since then she has been interviewed on various occasions about this claim, which gave rise to my decision to compile the following notes.

Since the 19th century, various Cuban intellectuals have constructed models for women’s rights. The Countess of Merlín reflected in her literary work her feminine feelings, her national roots and her points of view. Gertrudis Gómez de Avellaneda edited Álbum cubano de lo bueno y de lo bello, a woman’s magazine in which she challenged male domination and urged other women to do the same.

Marta Abreu, sublime personification of charity and patriotism, extended charity to the long-suffering people of the country when José Martí put the Cuban people on a war footing.Referring to her,Máximo Gómez said, “If you thought about what rank such a generous woman should occupy in the Liberation Army, I dare say it would not be difficult to see her on the same level as me.”

During the wars of independence Ana Betancourt de Mora defended female emancipation in the Constitutional Assembly of Guáimaro.

In 1895 María Hidalgo Santana joined the insurgent army and participated in the Battle of Jicarita upon the death of the standard bearer. She took up the battle flag, charged forward, received seven gunshot wounds and was promoted to captain. Edelmira Guerra de Dauval, founder and president of the organization Esperanza del Valle, helped to formulate the revolutionary manifesto of 1897, which stated in Article 4, “It is our wish that women be able to exercise their natural rights by allowing women who are single, widows over twenty-five years of age, or divorced for just cause, to vote.”

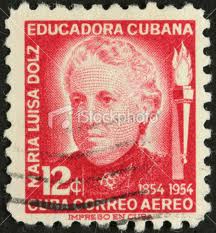

In 1897 María Luisa Dolz, a professor at Isabel la Católica girls’ school, linked educational reform to nationalism and feminism. For this she is considered to be Cuba’s first modern feminist.

In 1897 María Luisa Dolz, a professor at Isabel la Católica girls’ school, linked educational reform to nationalism and feminism. For this she is considered to be Cuba’s first modern feminist.

In the early days of the Republic a group of women founded associations and press outlets to defend women’s interests. Among them were Revista de la Asociación Femenina de Camagey, the first feminist publication on the island, Comité de Sufragio Femenino, Club Femenino de Cuba, Alianza Nacional Feminista,Lyceum, a predominantly cultural organization, which considered change to be impossible without access to education and culture, and Unión Laborista de Mujeres, a radical organization which gave priority to workers’ issues over women’s suffrage.

In 1912, after the crime against the members of the Partido Independiente de Color, a group of black women began a campaign seeking approval for a law granting amnesty to those who had been incarcerated. At their meetings and conferences they expressed support for women’s rights, such as the right to vote and divorce. In 1923, when the Asociación de Veteranos y Patriotas was formed, among its founding members were ten directors of Club Femenino de Cuba.

Among the notable women during the era of the Republic it is worth mentioning Mari Blanca Sabas Alomá, Ofelia Rodríguez Acosta, Ofelia Domínguez Navarro and María Collado, who played important roles in the struggle for women’s rights. They and other feminist leaders held conferences, submitted petitions to politicians, established coalitions among diverse groups, held street demonstrations, informed the public through print and broadcast media, built obstetric clinics, set up night schools and health programs for women, and established contacts with feminist groups in other countries.

Although the constitution of 1901 recognized the equality of all Cubans before the law, the Spanish Civil Code, still in-force at the time, held that women were inferior, which hindered their advancement and closed the door to women’s suffrage. Thanks to the civic movement of 1914, however, debates on divorce began to take place. On July 18, 1917 women were granted parental authority over their children and the the power to control their assets, and in July of 1918 the Divorce Law was adopted.

By 1919 Cuban women had achieved the same level of literacy as men, and in the 1920s Cuba was graduating proportionally as many women as American universities. These developments weakened those opposed to the female vote. In this context the battle for women’s suffrage gained strength.

In 1923 thirty-one organizations attended the First National Women’s Conference, and in 1925 seventy-one organizations attended the Second National Women’s Conference. As Pilar Morlón said, this was “a congress of women, conceived by them, organized by them, brought to fruition by them, without any official help whatsoever!” and, I would add, without any men presiding over the event.

This congress had such an impact that Cuban President Gerardo Machado promised to grant women the right to vote. When he named a constituent assembly to legalize his reelection, women’s suffrage was included among his proposals. Due to his failure to fulfill this promise, however, feminist groups allied themselves with other political groups after 1931, and when rebellion broke out, the issue of votes for women became a symbol of Machado’s abandonment of democracy.

On August 13, 1933, after Machado was deposed and Carlos M. de Céspedes (son and namesake of Cuba’s founding father) assumed the presidency, the Alianza Nacional Feminista sent an appeal to the new president, demanding the right to vote. Subsequently, the government of Ramón Grau San Martín promulgated Decree no. 13, which called for a constitutional convention, which in turn recognized a woman’s right to vote and be elected. Six women from the provinces of Havana, Las Villas, Camaguey and Oriente were elected as delegates.

In February 1934, during the presidency of Colonel Carlos Mendieta, a provisional constitution was approved. Article 38 of this document formally extended the vote to women. In February of 1939, prior to the Constituent Assembly, which drafted the 1940 constitution, the Third National Women’s Conference was held during which various resolutions were approved, one being the demand for “a constitutional guarantee of equal rights for women.” The feminists Alicia Hernández de la Barca from Santa Clara and Esperanza Sánchez Mastrapa from Oriente took part in this appeal, which was discussed in the Constitutional Assembly.

The struggle that began in the 1920s ended with the adoption of Article 97 of the constitution of 1940, which states that “universal, equal and secret suffrage is established as a right, duty and function for all Cuban citizens.” As a result, Cuban women were able to exercise their right to vote – including in the elections of 1940, 1944, 1948, 1954 and 1958 – until revolutionaries took power in 1959.

Dimas Castellanos

Published 13th November in Diario de Cuba.

November 16 2012