![]() 14ymedio, Reinaldo Poleo, Caracas, 11 November 2015 — Alex is one of those characters who leaves a mark on your life. He is a bright guy, a diligent scientist, methodical, focused. He has been this way since the day I met him, back in the eighties, when we were studying together at the La Salle Foundation on Isla Margarita.

14ymedio, Reinaldo Poleo, Caracas, 11 November 2015 — Alex is one of those characters who leaves a mark on your life. He is a bright guy, a diligent scientist, methodical, focused. He has been this way since the day I met him, back in the eighties, when we were studying together at the La Salle Foundation on Isla Margarita.

He is an avid reader, whose personality seems to come from a Franz Kafka work, with Herman Hesse for a father and Mafalda for a mother.

His patience dictated early on what he wanted to do: this man was definitely born to be a fish farmer.

He’s the kind you say was born in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Since we left manual labor, Alex has focused on fish production, which he has mastered to an extraordinary extent. He is a guy who should be developing this activity in a country that needs it as a way to produce proteins.

Alex has never doubted, he has fallen and he has risen. He is a worthy Venezuelan who has believed, does believe and holds fast to the dream; he is in the here and now suffering like every Venezuelan, he has no plans to flee, he has stayed to “try”…

For days we have been exchanging notes, talking about the things that are happening and what we think will happen or should happen. So here I am, sitting in a corner at the clinic, waiting for the doctor, when his whatsapp arrives. It is a message from a tired man. Sometimes tilting against windmills is tiring.

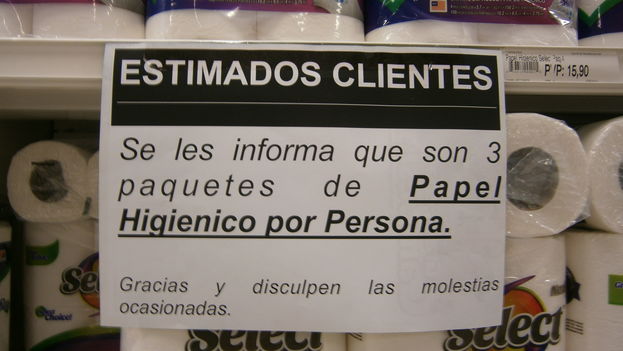

“Good friend, I have to climb Junquito in the morning and continue with the fish, but first I have to complete a ritual that belongs to my caste: go to the PDVAL [Venezuelan Producer and Distributor of Food].

“The ritual starts today, going to bed before eight in the evening to get a good night’s sleep, because, in addition to standing in line, if you want to buy anything, you have to get there before dawn.

“Usually I go at four in the morning, confident that the thugs, like nocturnal guácharos, are going to return to their dens and so it is possible that today will not be the last day I stand in line in this life.

“I get to the PDVAL and, like always, the ritual of my caste has started from the early hours of the day before. Those in the line tell me that they sleep on cardboard. I take my place at the end of those who are not of the so-called “third age,” those who make up the line.

“Not everything is that bad during the hours prior to the opening of the PDVAL. It is an interesting place to chat with other members of the clan and when the day dawns, they also begin to take the shapes of their silhouettes. And what silhouettes!

“At six, an Afro-descendent – I still don’t understand why it is bad to call them morenos and/or negritos – come by checking our ID’s and informing us in which batch it will be our turn to enter. There is still time to continue chatting and enjoying the silhouettes, which reminds me of a beautiful phrase from a friend of mine: ‘Superlative forms, almost insolent, of beauty.’

“At half past seven they open and the first batches begin to enter. Those pioneers, via cellphones, advise as to what is available and also begin to horde for their friends in the basic products lines. Thus, in entering, it’s common to see a man or a woman with a stroller with twelve chickens, for example, when you only get two per person.

“At nine it is my batch’s turn to enter. On hearing your name they take your ID and you enter. Something that always happens is that, on crossing the threshold, the people, literally, run to the shelves. I haven’t reached that level, but I do start walking faster.

“I turn first to where there is milk, rice, sugar, coffee and oil; only with luck will they have all of them. Then I go to the refrigerators looking for chicken at 70 bolos [bolivars] for a kilo and meat at 250. With great great luck, they will have both. Once having grabbed these products, you relax a little and look for some extras that you fancy. The final phase is the line to pay, as slow and cumbersome as the one to enter. By 11:00 I am out of PDVAL. I have completed the ritual.”

After such a story, I wonder if Lycra is the mandatory uniform, if some baby must be carried, and if there are large size ladies saving places for 10 housewives at the top of the line, to which he responds:

“Well, there are urban legends that say that in the PDVALs in the 23 y Enero parish, those in El Valle and La Vega, are only for the use of the clan called ‘that of the Colectivos.’

“Also there is the Clan of the Women, who come carrying their babies, and with another inside them, or another line with the blind and lame and people in wheelchairs; all that is missing to complete the picture is the spiritual master.”

He explains that the “urban legends” come from other historians in line, survivors of the above lines.

Finally the doctor shows up. I notice she is visibly upset: the insurance company wants to significantly lower her fees, she has to operate on a fractured tibia and fibula, displaced and open, of a member of the Clan of the Motorized. She asks 70,000 bolivars. As a fee, the company only pays 30,000. Immediately she tells me about the price of the dollar, her studies, the risks…

An operation like that for $87 dollars is absurd, and more absurd is trying to get her to do it for $37 dollars. She explains herself, she knows she isn’t paid in dollars, but in a country where everything is imported, it seems that we pay for things in dollars. Particularly, when a doctor can’t spend a day standing in line at a PDVAL, because the fallen “Motorized” can’t wait. Perhaps she will join the exodus of professional who have successful practices abroad. In Venezuela, we train excellent medical professionals, among others.

Our doctors have graduated in the daily practice of battlefield medicine, as they have seen the need to work in the worst sanitary conditions, with limited equipment and medicines, risking their lives when criminals kidnap them to save the life of a gangster, on pain of losing it if they fail.

The story of don Rey came to me in a similar way, a monthly pilgrim to the Social Security High Cost Medicines Department, who belongs to the Clan of those who fight against a Cancer. Once a month he meets with his Clan, from the early hours of the morning, waiting for the medicines he needs to confront such a terrible illness. Once again, he has missed a morning’s work, however, he couldn’t find the medicine; he waited for them to open to hear the news: There isn’t any.

A lady who comes from far away, with her head covered with a scarf, tries with difficulty to hide her lack of hair and dares to ask when they will have her medicine. The cold response from the official is the same for everyone: “I have no idea, there is no date.”

The next day, don Rey and the lady are there at the same time and he overhears the official denying her the medicine because “today, there isn’t any for you.” Crestfallen, the lady left, returning to her home more than three hours from the office intended to provide service to “the people.” Nobody says anything, everyone turns away, no one dares, if they deny you medicine it is a death sentence. The bald lady walks away in silence bowed by the weight of the death sentence on her shoulders.

Don Rey follows her with his eyes, a lump in his throat chokes him as he thinks about his own mortality. Don Rey loves life and endures humiliation because he wants to live.

His gaze pauses at the graffiti painted on the front wall, the sketch of a man with his hand raised and the legend that asks: “Free Leopoldo.” That boy and his family belong to the Clan of Political Prisoners, who also have their sentence.

In this precise instant, in the line at Locatel in Los Palos Grandes, Yuiriluz confronts Yuletzaida. Both are women of great size. The first is saving a place for her six friends, two of whom are pregnant and with babes in arm; the second said she had been there from early holding a place for another three. They are “resellers.” A push from Yuletzaida manages to make Yuiriluz fall headlong; a wad of notes and a cellphone falls out of her bra. The women in the line are trying to get away without losing their places, some men approach just to watch and, laughing, even place bets.

Yubiriluz rises with unusual agility while one of her friends collects her belongings from the ground, at the same time extracting a knife wrapped in lycra panties. The men step away, some shout. Before the astonished gazes of the rest of the line, she prepares to lunge at her attacker.

A couple of policemen from Chacao appear on their motorbikes, people shout after them, but they continue on their way without even blinking under their sunglasses.

However, something has changed, the armed woman moves away. Just this once Yuletzaida has been saved, surely tomorrow there will be another line for food, surely tomorrow she won’t have the same luck.

And so the days pass in our Venezuelan village: some loot to survive, while the most powerful build their empires with the dark elixer flowing from the ground

The dark troops fear the Clan of the North, it seems there are winds of war between the clans.

The Clan of the South looks after its regional tyrannies, disguised as democracy and people, while strengthening the defenses at the cost of hunger for the people.

And people live separated from each other, engaged in the struggles between their impoverished clans, bearing up under and dealing with their individual miseries.

The heroes falter under the gaze of a disunited people, critical from fear and waiting for help from the Messiahs from the North, they don’t know how to emerge from their own cowardice.

Some leave, others stay. But that is not important; what matters is that here or there they are finding their way to poverty, the mental poverty that kills dreams and numbs feelings.

Don’t think that we are all dead, every day I build my clan, with my family and friends. Every day that passes I speak about the Venezuela I dream of, and I have the pleasure of knowing more people who are waking up and beginning to dream, better still, they are starting to move in accord with their dreams.

My clan is increasing. In my clan we don’t loot, we work, we do not make war, but we are willing to give it.

In my clan we do not forge armies but ideas. In my clan we do not destroy, rather we strive to build.

In my clan, Alex will be the fish farmer we need, don Rey will live longer to enjoy the life his 74 years has given him. The lady with the headscarf will once again comb her hair, and the children of Yuletzaida and Yubiriluz, as well as those of their friends, will have the same opportunities that I had. Opportunities are not free, but a good government should create guarantees so that everyone can pay for them.

Because my clan does not belong to Generation Boba that waits for things to come from the sky or for a government that makes a gift to them of what they loot from the effort of others. It is time to make way for the builders, the critical and productive people, for true democracy and the defense of freedoms.