We observe a man who always speaks of patriotism and he is never patriotic, or only with regards to those of a certain class or certain party. We should fear him, because no one shows more faithfulness nor speaks more strongly against robbery than the thieves themselves.

Felix Varela (in El Habanero, 1824)

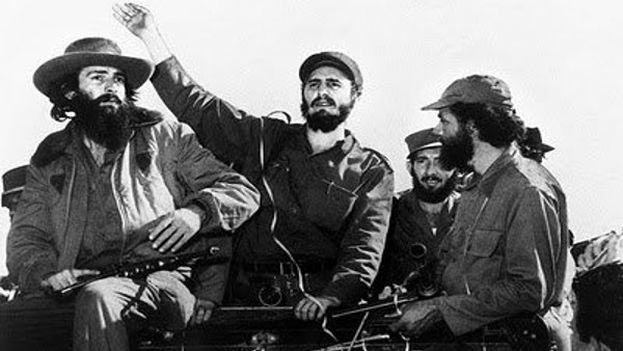

![]() 14ymedio, Regina Coyula, Havana, 19 May 2016 – Observing the tranquil surface of Cuban society offers a misleading impression. The stagnation is localized only in the government and in the party; and even there it is not very reliable. There is no doubt that many party members participated in and observed the 7th Congress of Cuban Communist Party (PCC) hoping for changes and, watching the direction of the presidential table, dutifully (and resignedly, why not) voted one more time unanimously.

14ymedio, Regina Coyula, Havana, 19 May 2016 – Observing the tranquil surface of Cuban society offers a misleading impression. The stagnation is localized only in the government and in the party; and even there it is not very reliable. There is no doubt that many party members participated in and observed the 7th Congress of Cuban Communist Party (PCC) hoping for changes and, watching the direction of the presidential table, dutifully (and resignedly, why not) voted one more time unanimously.

Outside this context, where one thing is said but what is thought may be something else, there is right now a very interesting debate in which all parties believe themselves to be right. The most commonly used concepts to defend opposing theses can be covered in the perceptions of revolution and democracy, which each person conceptualizes according to his or her own line of thinking.

There are generalities that are inherent in the concept itself. In the case of the concept of revolution, it involves a drastic change within a historic concept to break with a state of things that is generally unjust. Although it is a collective project, revolutions don’t always enjoy massive support; it is not until it is resolved that the great majority of citizens are included.

That said, from the official positions of the Cuban government they are still talking about the Revolution that overthrew the Batista tyranny and initiated profound changes in Cuba as a continuing event. This group believes itself still within the revolutionary morass, but can a country live permanently in a revolution?

One immediate consequence of a social revolution is chaos; everything is changing, and after a nation experiences a revolutionary process it needs stability to return to the path of progress, a natural aspiration of society and of the individual.

The 1959 Revolution became a government many years ago and its young leaders are, today, old men who in their long time in power ensured mechanisms for the control of the country. It could be nostalgia for not having been there or it could be comfort with the idea of having made mistakes and implemented bad policies, all justified as an appropriate effect of the revolutionary moment.

It is here that democracy intervenes. Whatever kind it is, it must characterize itself because popular decisions are effective; directly or through the leaders elected through voting. And also through debate. One can’t insist on continuing to wear children’s clothes when one is an adult. Norberto Bobbio’s concept is always widely accepted: without recognized and protected human rights there cannot be a real democracy, and when we are citizens of the world, and not of one state, we are closer to peace.

We do not live in a democratic country, however much they want to minimize the lack of freedoms and blame it on the “blockade,” the “imperialist threat” and novelties such as “opinion surveys” or “media wars.” Because democracy is an umbrella that should also protect minorities of every kind.

We can see vestiges of Marxism-Leninism in this stumbling march toward capitalism without democracy, we see in the free state version of the idea enclosed in this disturbing paragraph of a letter from Engels to August Bebel, regarding power and those who oppose it: “So long as the proletariat still makes use of the state, it makes use of it, not for the purpose of freedom, but of keeping down its enemies and, as soon as there can be any question of freedom, the state as such ceases to exist.”

Where are the rights of minorities? How do we know if they are real minorities? So far, certainly, the public support for the government has been a matter of trust, but the suspicion showed by the government when asked for transparency is striking.

From the polemics that are shared among websites and from closed-door meetings to emails and the chorus of the interested, and from there to the classic rumor on the street, it is clear that there is an imperative to widen the debate. Patriotism is not a state monopoly nor is it reflected only in talking about history and honoring symbols, much less in the cult of personality, which by the way, this year promises North Korean dimensions.

One of the ideas that is addressed in this debate is the danger posed by “non-revolutionary transitions in the name of democracy,” but we know that this is a concern of the hardline defenders of that model that they stubbornly insist on calling socialist; ‘they’ being those who consider themselves anti-imperialists, those who “won’t budge an inch,” and who sleep peacefully without looking for other culprits for the collapse that surrounds them on all sides.

My concern as a citizen is not having democracy in the name of the Revolution.