It’s just been born and in a few hours they will register the baby with its brand new name. A few days will pass before the parents get the birth certificate and then the so-called “minor card.” Without an identification card you can’t receive products from the ration market, enroll in school, get a job, travel on an inter-provincial bus, or put your belongings in a bag-check at a shop. Every day of your life you need this document, which at the top carries a unique combination of eleven digits. On the little piece of cardboard your temporal and geographic data is registered… and also certain physical details.

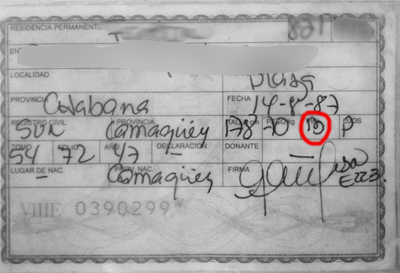

It looks just like a letter on the back of the identity card, but it is an initial that describes the color of our skin. This consonant classifies us as one race or another, divides us into one group or another. Amid repeated institutional calls to end discrimination, the Cuban Civil Registry still maintains a racial category for every citizen. Along with the date of our birth, and our address, it specifies if we are white, mixed or black. The assignment of a “B,” “M” or “N,” (Blanco-white, Mestizo-mixed, Negro-black), in a nation with so much race mixing, is often the result of a functionary’s subjective judgement.

Amid so many priorities, so many rights to demand and injustices to end, it might seem trivial to demand the withdrawal of a letter on our identify card. However, its small presence doesn’t diminish its gravity. Especially when the document itself already has a photo of its holder, where you can see his or her physical features.

No citizen should be evaluated by the color of their skin, nor placed in a category according to the amount of pigment they carry in their epidermis. Such bureaucratic backwardness speaks more to prison files than civil registries. It’s not a question of melanin, but of principles.

17 February 2014