Then someone suggested: “On Friday March 28th (I’m going back to March 28, 2008) there’s going to be the closing ceremonies for the First International Festival of Young Storytellers of Havana, at 1:00 pm at Casa de las Americas, why don’t you prepare something?” And they added: “In the morning Blessed are those who mourn is going to be presented, the book that won Ángel Santiesteban the Casa de las Americas prize in 2006,” which at that point was still missing from the bookstores in Havana.

I arrived in the afternoon. No sign of any writers (young or old), and no indication of any festival, meeting, conference, colloquium…which I knew had been planned. However, behind the little counter where editions of the Fondo Editorial Casa were exhibited, a girl smiled.

“It’s a book that is controversial,” she said, without going into detail. “There are no copies left in the warehouse. They are printed abroad, and we hope that they will arrive any moment now…. “ continue reading

I forgot about the “festival of storytellers,” but curiosity about the fate of the volume, which was awarded a prize two years ago, prodded me with renewed spirit. A couple of days later, I sent an email to its author, who I didn’t know personally. His response confirmed the saying, “It would seem the boat that brings the books went astray,” he wrote. I thought I perceived in his tone a respectable dose of irony. He promised to get it for me, and then I didn’t hear from him.

One afternoon, visiting the Manero Workshop, located in the capital district of La Ceiba — and where not just painters but also writers and artists of all stripes hang out — Ernesto Pérez Castillo had the kindness to give me an unusual anthology:The Ones Who Count, published by Editorial Cajachina del Centro de Formación Literaria Onelio Jorge Cardoso. Among the short stories was one from Ángel:”The Round Night,” which, by the recurring theme of the presidio, I suppose was taken from the phantom book.

The following link in the chain was to search on the Internet for the story entitled “Hunger”. I accidentally discovered it on some blog, I don’t remember which one. It was a short story, without excessive stylistic pretensions, an “easy” read.

In effect, “Hunger” is an anecdote that impacts by its simplicity. A convict complains when they turn off the lights. He is hungry. “I’m not a trouble-maker or anything,” he alleges. Or something in that style. “Can someone find me a yam, a few scraps? That would be enough for me,” he continues, while the guards insist on making him shut up. The argument gets louder, and the convict ends up gagged in a punishment cell. The rest of the night passes in silence. Until dawn, when they find him and take him back to the cell block.

It’s amazing that such a simple story flows with a level of suggestion that doesn’t detract from its spontaneity and power. The hunger of “Hunger” starts stifling the reader as he continues to read. The protagonist feels an atrocious appetite that impels him to defy the rules, no matter how rigid. He is just a prisoner, a common man deprived of liberty, whose hunger they cannot silence. Nothing more.

More exactly, it has a leisurely prose that appears to distance itself from the tormented stories in South: Latitude 13 (UNEAC short story prize 1995) and The Children Nobody Wanted (Alejo Carpentier Short Story Prize 2001). And there is no spiritual calm in “Hunger”; nor is there in the rest of the stories that complete the tome (which I finally obtained – autographed by the author – during its “official” launch in the Palacio del Segundo Cabo, the former seat of the Cuban Institute of the Book).

I say “leisurely prose” thinking about the gulf between narrator and historian. In “Hunger” the writer doesn’t express the drama with the intensity of South.There isn’t the same experiential load; the story isn’t painful. The chance of being estranged (that I cannot explain) admonishes us to perceive the emotions from a passive angle. Even with humor. And with a certain cunning.

Before “Hunger” I had read Santiesteban with some apprehension. Not for his lack of gifts as a narrator, but precisely because of the stories he preferred to tell. Were they excessively stitched from the Cuban reality? I’m not sure. But we are so saturated after a decade of balseros (rafters), prostitutes and predators of high rank. In these years there was nothing that was different. The now-young writers — I wouldn’t know what adjective to foist on them after having worn out the term “newest” — declined categorically to maintain the rhythm. The new narrative, no less iconoclast, doesn’t go to war now, nor does it abandon the country in a rustic boat. The generation of the 90s, with its “the last will be the first,” remains on the margins.

Naturally, a book like South: Latitude 13 saves itself under any circumstance. For many reasons, beyond literary quality. The craft of story-telling and intuition abound in these desolate texts, profoundly human, insomuch as the subject of war and the bellicose Cuban campaigns in Africa function in two ways: as a pretext for settling any moral doubt accumulated during 30 years and as a comprehensive view, a global look, at a living tragedy. No other story-teller of his quality managed to scale that height. Not even the mutilated version of Dream of a Summer Day (Ediciones UNION, 1998) can undermine the profound anti-epic quality that breathes there.

In The Children Nobody Wanted, he presents us with the question of prison, the other grand obsession of the artist. The characters are caricatures, disoriented, sometimes ridiculous. Always torn apart. Santiesteban chooses a subject little visited before by Cuban literature (except perhaps for the narrations of Eladio Bertot and Carlos Montenegro). The condemned (the children?) of The Children… serve their time in inexact latitudes, in imprecise times. Scarce reference points are given to situate the plot: King Kong, the Morro lighthouse, a song of Julio Iglesias….The writer evades descriptions, by profession. Perhaps he judges them unnecessary. By definition, aren’t they?

Blessed are Those Who Mourn would then come to constitute a lucky saga of those first stories about jail. Speaking of that “hard and excellent” book, I am not going to repeat myself: At that moment I conceived of a review (“Writing with the voice of crying”), published in Isliada.com.

In the same way that “Hunger,” with its apparent argumentative laziness — although full of vivid insinuations, realistic as its own title — I received the news of the prison sentence. The Cuban narrator,one of those who attained national and international recognition during the last two decades, has merited, not a prize, but the sanction of five years of privation of liberty, as an author, not from a literary text, but from the crimes of house-breaking and assault.

In a recent post (of the few I’ve had the chance of reading), the writer declares himself innocent and attributes the persecution to his political activism. The sentence, handed down by the Peoples’ Provincial Criminal Court, was first given to him on December 6, 2012, and as authorized under the law, his defense attorney filed an appeal before the Supreme Court.

In summary, if our highest jurisdictional organ doesn’t overturn the decision, Angel Santiesteban’s days of freedom are numbered. I’m amazed that such a complex story has gone on with a level of suggestion that borders on apathy and muteness.

In fact, information comes to my in-basket (courtesy of some of my contacts) and tells a strikingly crude tale. A writer complains, not when they turn out the lights, not because he is hungry. Estrangement fades and rallies us to perceive emotions from an active angle. Without any humor. “I’m not a trouble-maker or anything,” perhaps the accused character alleges. I don’t know. I can’t make him responsible for the infractions that they say he has committed. I can’t absolve him. I can’t swear to anything: Nothing has been said in the press (of course not — some smart-ass will surely make fun of him — nor did they say anything about the trial of Augustin Bejarano in Miami).

I can only say that I knew Angel Santiesteban, not with the necessary depth to call him a friend; that the bonds of brotherhood brought us close, without bothering to mention now that my Masonic affections don’t show sign of any recuperation. I can also say that I’ve read his work and that, since then, I’ve been a better human being, much more open and sensitive to someone else’s pain. Lastly, I can say that an artist of his stature does not deserve — although crushed by the worst misfortune — that the rest of the night pass in silence, until at dawn (as with the protagonist in “Hunger”) they look for him to reintegrate him into the cell-block.

Throwing a writer in jail is the lowest form of tragedy.

And tragedies never have a happy ending.

Published in: VerCuba

Translated by Regina Anavy

Translator’s note: Between the original writing of this text and its translation the Supreme Court upheld Angel’s sentence.

January 19 2013

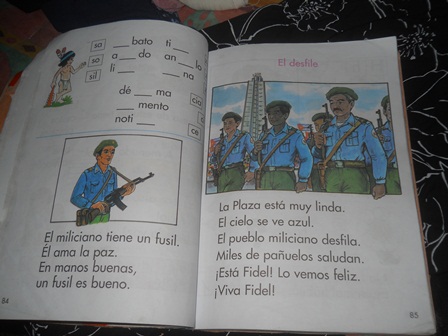

Text in schoolbook: The soldier has a gun. He loves peace. In good hands, a gun is good. The Plaza is very pretty. The sky is blue. The people’s militia parades. Thousands of handkerchiefs salute. It is Fidel! We see him happy. Long live Fidel!

Text in schoolbook: The soldier has a gun. He loves peace. In good hands, a gun is good. The Plaza is very pretty. The sky is blue. The people’s militia parades. Thousands of handkerchiefs salute. It is Fidel! We see him happy. Long live Fidel!