The Best Site in Pinar del Rio / Henry Constantin

What makes a city is its people. The Capitol is not the most important thing in Havana, nor are the abundance of churches and alleys what is most striking of Camagüey, nor is the Moncada Barracks the greatest thing in Santiago, nor are their seawall walks the most pleasant parts of Caibarién, Cienfuegos, Gibara and Puerto Padre. It is the people who live or have lived there, their work, their faith, their worth or their dreams, who give meaning to those places.

What makes a city is its people. The Capitol is not the most important thing in Havana, nor are the abundance of churches and alleys what is most striking of Camagüey, nor is the Moncada Barracks the greatest thing in Santiago, nor are their seawall walks the most pleasant parts of Caibarién, Cienfuegos, Gibara and Puerto Padre. It is the people who live or have lived there, their work, their faith, their worth or their dreams, who give meaning to those places.

And Pinar del Rio is a city that — forgive me for all the other valuable things that don’t appear in this blog — makes more sense because in many of its houses, ever stronger, grows the magazine Coexistence.

Occasionally Dagoberto Valdés, friend and editor of the magazine Coexistence, sends me a text message, a text that is not like the others, although it is also news: there is an Editorial Board. And I must be, and the finicky editor of texts that he lets loose in his alert counsels, and I’m glad because I cam going to see a ton of friends and good people, “good for me and good for this island bathes in waves of despair,” all at once.

So once more I pack my backpack, and correct the commas in an article I’m sure I haven’t sent them yet, and get a ticket or hang around the waiting lists at the bus stations. And begin the trip to Pinar del Río.

I’ve traveled a lot to the city that seemed a remote land before: since that first trip of curious journalist, when with my beard and covered in road dust I arrived at the home of Dagoberto Valdés, a few months from the end of the magazine Vitral, to help put out the first issue of White Rose. And instead of people consumed by sadness or resentment against the deserters, and the every-man-for-himself in which so many Cubans sail today, I found a team focused on their work, optimistic and affable, wonderfully resilient.

(That was my first trip to Pinar del Rio and the Magazine, in a very journalistic and traveling summer, when I still hadn’t been out of the University of Santa Clara did two months later, which I was two months later, by chance. And I joined the Editorial Board in February 2011, my own birthday present, four months before I was kicked out of the ISA. Obviously, my relationship with the magazine had a strong impact on me).

The red signs announces the closing of the workshop (also a museum) after 13 years, and the blue sign says “Strictly Forbidden to Stop Dreaming”*

Coexistence brought me to the home-based museum of Pedro Pablo Oliva*, and The Great Blackout epic my Cuban favorite. Coexistence gave me the chance to film, which I still owe them for, when a phenomenal jury gave Henry Constantin its audiovisual prize. Coexistence, that had managed to weave together a ton of friends in Pinar del Rio and outside the city, which they shared with me.

And Coexistence included me in its Editorial Board, and that night of the first meeting my modesty about being an upstart, for being the last to arrive and from the farthest away, they treated me almost equal to the founders, freely and without hesitation, with the right to edit and critique every new issue of the magazine.

Usually the traveler goes to see Soroa and Las Terrazas, climbs the hills of Vinales or goes down in the caves of Santo Tomas, spends an afternoon at Guyabita or breathig in the best tobacco brangs, bathing in Maria La Gorda, taking the waters of Los Portales and looking how it flows to the Gulf of Mexico from Cano de San Antonio or enjoying the clouds from Pan do Guajaibon.

All that is good, if one wants to know only the superficial. But if you want to know something of the best of humanity reborn in Pinar, and you left without a greeting to the people of Coexistence, without the magazine, a photo or a conversation, the traveler, possibly, would have missed everything.

Henry Constantín

*Translator’s note: Pedro Pablo Oliva is a painter in Pinar del Rio who fell on the wrong side of the government. The associated events are detailed here by: Yoani Sanchez, Dagoberto Valdes, Miriam Celaya and Orlando Luis Pardo Lazo.

20 March 2013

If They’re Serious About Saving / Fernando Damaso

The country’s leading authorities continually talk about the need to save resources and use the limited ones that are available for important issues, to support development and help in solving the many existing problems and overcoming the shortages. Undoubtedly, it is a fair demand, but it would be even more so, if they looked within themselves, and decided to save on those government activities that represent large expenditures and provide no wealth.

I am referring to the high subsidies enjoyed by the so-called mass organizations (CDR, FMC, CTC, ANAP, FEU, FEEM and others)*, institutions that present themselves as NGOs, but are, in fact, far from it; they are organized, directed and primarily funded by the State and solidarity groups abroad and while visiting Cuba; in addition there are some political campaigns, including that for “The Five**” (with the current adaptation of a mansion in El Vedado*** for its headquarters), payment of attorneys and multiple trips around the world for their families.

If they reduced the inflated payrolls of professional staff of these organizations, groups and campaigns, we would see a substantial savings in salaries, travel and maintenance, along with the great amount of free transport, housing and locales (usually the best), in municipalities as well as and in the provinces, helping to increase the housing stock to the public.

These measures don’t need commissions nor long studies and experiments for their implementation, as the sad reality already one of general control. If these savings also include major political organizations and some super-ministries, which enjoy carte blanche to own vehicles of all types, buildings, homes and locales (often underutilized), the results would be even greater and would be approved by the majority of citizens.

That is, if you really want to save, there is enough fabric available to cut within the State, without trying to apply them only to ordinary Cubans, demanding greater sacrifices.

Translator’s notes:

*All of these organizations are arms of the government: CDR =Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (the block watch groups); FMC = Federation of Cuban Women; CTC = Cuban Workers Union; ANAP = National Association of Small Farmers ; FEU = Federation of University Students; FEEM = Federation of High School Students.

**”The Five” refers to five Cubans found guilty of spying in the United States. Four of the five remain in prison. The Cuban government presents them as national heroes unjustly convicted.

***El Vedado is one of the nicer neighborhoods in Havana.

30 March 2013

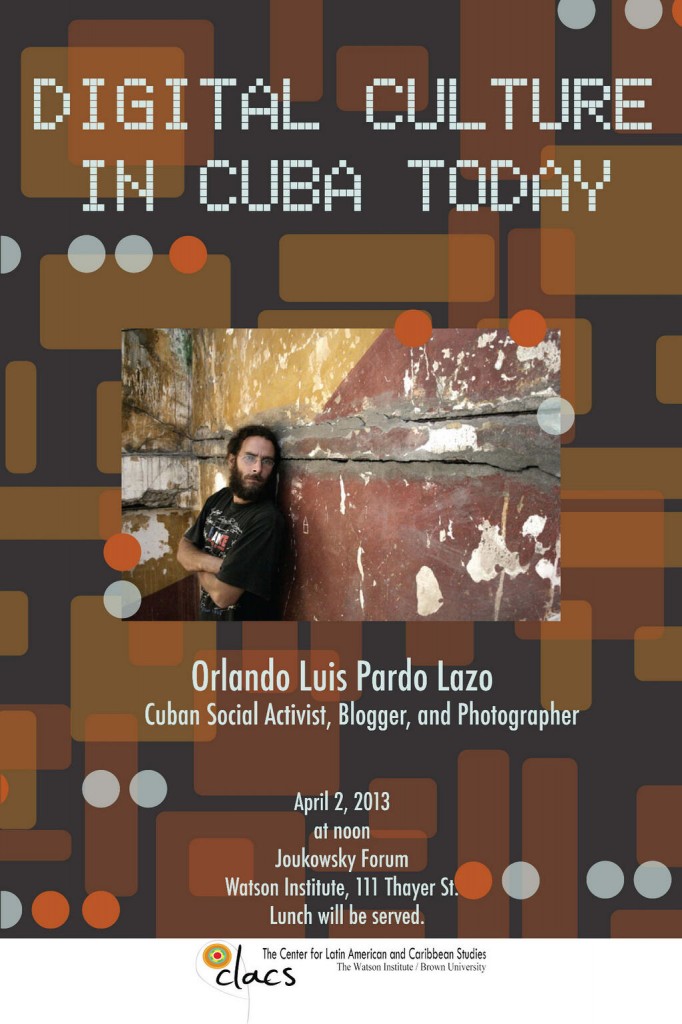

Orlando Luis Pardo Lazo at Brown University: Video is Now Available On-Line

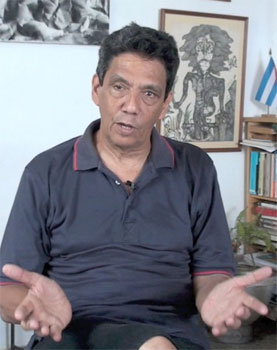

Two Part Interview of Reinaldo Escobar From Havana Times / Reinaldo Escobar

By Yusimi Rodriguez (Translation from Havana Times)

By Yusimi Rodriguez (Translation from Havana Times)

HAVANA TIMES — For months I had wanted to interview Reinaldo Escobar – the blogger and moderator of an audiovisual panel discussion project called Razones Ciudadanas. He’s also the husband of blogger Yoani Sanchez, who is currently on an international tour.

We met up at a cafe in the upscale Miramar district and before I could pose the first question, he summarized his life.

Reinaldo Escobar: I was born in Camaguey in 1947, I graduated in journalism and I took five post-graduate courses in Marxism.

HT: Marxist?

RE: Marxologist.

At the end of my studies they wanted to kick me out of school for being smug, hyper-critical, immature, and having literary tendencies. The punishment was to send me to the Centennial Youth Column in Camagüey – not as a cane cutter though, but as a journalist. I stayed there for eighteen months.

Later I worked for the magazine Cuba Internacional, and afterwards at the Juventud Rebelde newspaper. After a year and a half, on December 18, 1988, I was told in a meeting that I couldn’t continue there or work in the field of journalism any more in Cuba. I was transferred to the National Library, where, along with others, I requested a meeting to discuss the agreements of the Fourth Party Congress. We were met with a “repudiation meeting” and I decided to leave.

Then I was an elevator mechanic and a librarian at a technological institute until 1994. That was my last government job. Then I taught Spanish to foreigners. In 2004, I founded, with other friends, the magazine Consenso, which evolved into the digital portal Desdecuba. There I learned digital journalism with Yoani, and I started my blog.

Part 2

By Yusimi Rodriguez

HAVANA TIMES – Journalist Reinaldo Escobar was booted from the official Cuban media back in 1988 but he has continued writing his critical commentaries most recently on his blog desdeaquí.

The husband of blogger Yoani Sanchez, one of the 100 most influential persons in the world according to Time magazine for 2008, is currently minding the fort while Yoani is off on a worldwide tour. The following is part two of our interview with Escobar. See part one.

HT: Why remain a Marxologist?

Reinaldo Escobar: I think that Marxism is subversive in Cuba today. The official Party policy on economics is anything but Marxist.

HT: However aren’t the economic changes taking place in the country are going in the right direction?

Reinaldo: Yes, but they are not Marxist.

HT: So Marx was wrong?

Reinaldo: At that moment in time, no, but his theories are no longer applicable. Marx said practice is criterion for evaluating truth. Practice shows these ideas do not work. My friend Victor Fowler says you have to start thinking about infeasibility being a constant feature of the socialist system.

February 2013

Yoani Sanchez Speaking at Freedom Tower in Miami / Yoani Sanchez

Yoani’s presentation at Miami Dade College’s Freedom Tower in Miami with an English voice over.

Yoani’s presentation at Miami Dade College’s Freedom Tower in Miami: the original, in Spanish.

1 April 2013

Watch Orlando Luis Pardo Lazo Live Now at Brown University

Into the White House, Out of the U.N. / Orlando Luis Pardo Lazo

Recently, from Washington, D.C. to New York, renowned Cuban blogger Yoani Sánchez and I have shared some unforgettable days together as pro-democracy activists.

After a complicated process involving application forms and NGOs, we were welcomed in Washington by U.S. Representatives, members of Congress, senators, and by various ministries of the White House and the State Department.

During those very brief, but intense encounters, the focus was on mutual respect for each other’s opinions, the process of building bridges through dialog (something that the Cuban State military will never forgive us for), and on looking towards a future of understanding rather than dwelling on a past of irreconcilable mistrust. There was a lot of good humor too, with smiles replacing the fear that might have still been dwelling in our hearts.

With its monumental spaces and its winter nights, which we shared with a community of Cubans, who until then knew us only through the internet, Washington seemed like the most civil city in the world, free of armed troops guarding government buildings, and with a sea of students excitedly visiting Capitol Hill and the White House. Such a thing would be inconceivable at the ministries in my country.

Read the rest of this article on Sampsonia Way Magazine

1 April 2013

Watch Yoani Live and in English Speaking in Miami / Yoani Sanchez

Cubans, period

Freedom Tower, Miami

Years ago, when I left Cuba for the first time, I was in a train leaving from the city of Berlin heading north. A Berlin already reunified but preserving fragments of the ugly scar, that wall that had divided a nation. In the compartment of that train, while thinking about my father and grandfather – both engineers – who would have given anything to ride on this marvel of cars and a locomotive, I struck up a conversation with the young man sitting directly across from me.

After the first exchange of greetings, of mistreating the German language with “Guten Tag” and clarifying that “Ich spreche ein bisschen Deutsch,” the man immediately asked me where I came from. So I replied with “Ich komme aus Kuba.”

As always happens after the phrase saying you come from the largest of the Antilles, the interlocutor tries to show how much he knows about our country. “Ah…. Cuba, yes, Varadero, rum, salsa music.” I even ran into a couple of cases where the only reference they seemed to have for our nation was the album “BuenaVista Social Club,” which in those years was rising in popularity on the charts.

But that young man on the Berlin train surprised me. Unlike others, he didn’t answer me with a tourist or music stereotype, he went much further. His question was, “You’re from Cuba? From the Cuba of Fidel or from the Cuba of Miami?”

My face turned red, I forgot all of the little German I knew, and I answered him in my best Central Havana Spanish. “Chico, I’m from the Cuba of José Martí.” That ended our brief conversation. But for the rest of the trip, and the rest of my life, that conversation stayed in my mind. I’ve asked myself many times what led that Berliner and so many other people in the world to see Cubans inside and outside the Island as two separate worlds, two irreconcilable worlds.

The answer to that question also runs through part of the work of my blog, Generation Y. How was it that they divided our nation? How was it that a government, a party, a man in power, claimed the right to decide who should claim our nationality and who should not?

The answers to these questions you know much better than I. You who have lived the pain of exile. You who, more often than not, left with only what you were wearing. You who said goodbye to families, many of whom you never saw again. You who have tried to preserve Cuba, one Cuba, indivisible, complete, in your minds and in your hearts.

But I’m still wondering, what happened? How did it happen that being defined as Cuban came to be something only granted based on ideology? Believe me, when you are born and raised with only one version of history, a mutilated and convenient version of history, you cannot answer that question.

Luckily, it’s possible to wake up from the indoctrination. It’s enough that one question every day, like corrosive acid, gets inside our heads. It’s enough to not settle for what they told us. Indoctrination is incompatible with doubt, brainwashing ends at the exact point when our brain starts to question the phrases it has heard. The process of awakening is slow, like an estrangement, as if suddenly the seams of reality begin to show.

That’s how everything started in my case. I was a run-of-the-mill Little Pioneer, you all know about that. Every day at my elementary school morning assembly I repeated that slogan, “Pioneers for Communism, we will be like Che.” Innumerable times I ran to a shelter with a gas mask under my arm, while my teachers assured me we were about to be attacked. I believed it. A child always believes what adults say.

But there were some things that didn’t fit. Every process of looking for the truth has its trigger, a single moment when a piece doesn’t fit, when something is not logical. And this absence of logic was outside of school, in my neighborhood and in my home. I couldn’t understand why, if those who left in the Mariel Boatlift were “enemies of the State,” my friends were so happy when one of those exiled relatives sent them food or clothing.

Why were those neighbors, who had been seen off by an act of repudiation in the Cayo Hueso tenement where I was born, the ones who supported the elderly mother who had been left behind? The elderly mother who gave a part of those packages to the same people who had thrown eggs and insults at her children. I didn’t understand it. And from this incomprehension, as painful as every birth, was born the person I am today.

So when that Berliner who had never been to Cuba tried to divide my nation, I jumped like a cat and stood up to him. And because of that, here I am today standing before you trying to make sure that no one, ever again, can divide us between one type of Cuban or another. We are going to need each other for a future Cuba and we need each other in the present Cuba. Without you our country would be incomplete, as if someone had amputated its limbs. We cannot allow them to continue to divide us.

Just like we are fighting to live in a country where we have the rights of free expression, free association, and so many others that have taken from us; we have to do everything – the possible and the impossible – so that you can recover the rights they have also taken from you. There is no you and us… there is only “us.” We will not allow them to continue separating us.

I am here because I don’t believe the history they told me. With so many other Cubans who grew up under a single official “truth,” we have woken up. We need to rebuild our nation. We can’t do it alone. Those present here – as you know well – have helped so many families on the Island put food on the table for their children. You have made your way in societies where you had to start from nothing. You have carried Cuba with you and you have cared for her. Help us to unify her, to tear down this wall that, unlike the one in Berlin, is not made of concrete or bricks, but of lies, silence, bad intentions.

In this Cuban so many of us dream of there will be no need to clarify what kind of Cuban we are. We will be just plain Cubans. Cubans, period. Cubans.

[Text read in an event at the Freedom Tower, Miami, Florida, 1 April 2013]

RIP Chavez: The caudillo‘s death sends public into “collective hysteria” / Orlando Luis Pardo Lazo

When my plane took off from Havana, Hugo Chávez was still alive. When I landed in Miami less than an hour later, the Venezuelan president was dead. The Cubans on the plane were celebrating together. Fireworks were soon set off in Miami. From what I saw jubilation was the first response to the death of a caudillo that would have stayed in power forever. Bio-revenge.

It’s possible that Hugo Chávez had already died in Cuba long ago. It’s possible that a corpse traveled from Havana to Caracas. When governments practice secrecy, there are no limits to the insanity or criminal despotism.

On the day of Chávez’s death, a unprofessional presenter on Cuban TV almost cried on camera and beat his chest as he read the Official Statement.

Then came the collective hysteria around the change of government, something that should be only a constitutional process. Later, as macabre as it got, the government announced that they were going to mummify Chávez, although one week later they changed their mind.

Read the rest of this article on Sampsonia Way Magazine

18 March 2013

Yoani Sanchez: An effective voice against the Castro dictatorship / Carlos Alberto Montaner

From El Blog de Montaner

From El Blog de Montaner

Yoani Sánchez visits Miami. It is the most difficult stop in her long tour. Everywhere, like a bullfighter hailed after a good afternoon, she has been carried on the shoulders of the crowd. She will also triumph in Miami, but her task will be a bit harder.

I get the impression that a huge majority of Cubans like her and respect her — I count myself among them — but there’s no shortage of those who oppose her for various reasons, often totally irrational.

Yoani has made dozens of appearances, granted hundreds of interviews and has successfully confronted the mobs of supporters sent by the Cuban dictatorship in every city where she has been invited to speak.

In more than half a century of tyranny, nobody has been more effective in the task of dismantling the regime’s myths and exposing Cubans’ miserable living conditions.

It is a paradox of life that, somehow, the rude and vociferous attitude toward Yoani shown by these aggressive bullies — though unpleasant during the incidents themselves— has served to feed the interest of the communications media and foster the support of notable political and social sectors.

These maniacs, accustomed to the Cuban environment, where no vestiges of freedom exist, don’t understand that trying to silence Yoani, insulting and slandering an independent journalist, a fragile young woman shielded only by her words and her valor, is counterproductive.

Yoani’s weapons have been sincerity, a crushing logic, an innate ability to communicate, and her own attractive personality. That is, the same features that gradually attracted, first, the curiosity of the major media and institutions — Time, El País, The Miami Herald, Foreign Policy, Columbia University — and later the admiration of millions of readers throughout the world who found in her chronicles a balanced description of the impoverished madhouse called Cuba.

The regime of the Castro brothers, convinced (or at least intent on convincing others) that behind every criticism lurks the hand of the United States, capitalism or dark economic interests, tried unsuccessfully to demonstrate that Yoani was a puppet of the CIA., the Prisa Group or some artificial manufacturer of prestige.

None of that. As usually happens, Yoani’s talent, unpredictable luck and the attacks from the dictatorship made her the focus of the major information distribution centers. One result was that, by the time the journalist was extremely famous, President Obama himself answered a list of questions for him that appeared on her blog.

That could have happened to other notable bloggers inside Cuba — Claudia Cadelo, Iván García, Luis Cine, among other good writers — but it was Yoani on whom international public opinion concentrated, aware of the harassment and mistreatment by the regime.

Throughout that never-ending tyranny, Huber Matos, Armando Valladares, Eloy Gutiérrez Menoyo, Gustavo Arcos, Ricardo Bofill, María Elena Cruz Varela, Reinaldo Arenas, Marta Beatriz Roque, Laura Pollán, Raúl Rivero, Oswaldo Payá, now his daughter Rosa María, and other brave Cubans have found a platform and sounding board for their denunciations as a result of the abuse to which they were subjected.

If the first time that Yoani Sánchez received an invitation and a visa to travel abroad, the dictatorship had allowed her to exercise her right to leave and reenter the country freely, she would not have gained the huge celebrity and weight she now enjoys.

Why didn’t the government do it? Because of a mixture of arrogance and stupidity. Because it believed that it could crush people without any consequences.

Fortunately, that’s not true. The people’s voice is the strong voice of the weak. “A just principle from the bottom of a cave is more powerful than an army,” José Martí wrote.

Welcome to freedom, Yoani!

Carlos Alberto Montaner

L is for Liberty / Henry Constantin

A beheaded Indian atop his white horse races around Las Tunas, this faded and drab Eastern balcony what I love so much because there they have loved me. The Indian is a bad omen, according to the elders of Las Tunas, perhaps because of the already genetic fear of a population that in the 19th century was attacked too often and burned too often. There are those who say, to spread fear at night, that the last apparitions of the headless one were before an apocalyptic hailstorm and a bloody car accident many years ago. But it has not come out again.

And I think it’s because, decapitated after all, he has no head to see his surroundings. Because a subtle tragedy, without blood or fury or visible cataclysms, happens every day. In the schools of Tunas — as its citizens abbreviate Las Tunas — and in the whole country.

If you travel to the village of Cucalambé — eminent poet of Las Tunas, whose formal name was Juan Cristóbal Nápoles Fajardo – drop in on Vicente Garcia park. Look at the statue of the much-discussed gallant general, walk through the bright new boulevard that stretched from the little Catholic church, have an ice cream at Las Copas, take a peek at Jose Marti Plaza, the most inventive Cuban monument to the man from Dos Rios. All that is very nice. But if you don’t want to upset yourself, don’t want any further on the boulevard that Ramon Ortuno Street.

Because a few blocks further on, like someone looking for the bus station, there’s a nursery school, a kindergarten — as the grandparents call it — that is called “Little Friends of MININT,” that is the Ministry of the Interior. I went through there at the same time as the parents were picking up their kids under 5, who do not read or write, but who surely have already received lectures in that place about the institution in charge of control and exhaustive surveillance over Cubans, those who spy, interrogate, beat and imprison people. I discovered that place and, dying of laughter at the excessive brainwashing, took a a picture of it. Then came the bitterness.

Bitterness is not the name of the place, which is just a detail in the landscape of Cuban education. The bitterness is because I remembered that I’m alive and I have a son who lives in a country where all this, these kindergartens for toddlers, primary and secondary schools for kids and teens, the high schools and poly-techs, and the universities belong to the state. And those who control the state — which I insist on writing in lower case, because that’s how I think of them — manage them without any ethical respect for our children.

On the contrary, they use them to teach and evaluate the discipline of their own political ideas. And worse: they train them in the arts of obedience, of saying yes when they think no, of setting aside their truth, of running away when they can’t take it any more. Without the permission of the parents, who also took the same classes.

Once I asked Dante, my son, who just turned 7,what letter he’d learned that day. “F for Fidel,” he answered. Not F for Family, which is what I try to teach him, not F for fortunate, which is what he deserves. No, those were not the most important words he learned that day. That day he learned F, for Fidel.

They saw education in Cuba is free. I don’t know. It’s true that in exchange for so much schooling and education the government doesn’t ask us for money, no. It asks us to give our liberty, which is worth more.

The Indian doesn’t go headless any more in Las Tunas. Or there is no disgrace to say it, or those it happens to are so used to it and silent, that that rider on a white horse dissolves in the past. But this April 4th there’s a party for our children, the students, who, for now, continue in that only possible — free and compulsory — school. For now.

1 April 2013

Habemus Papa / Miguel Iturria Savon

From a town on the Spanish Mediterranean I just witnessed on television the designation of the new Pope of the Catholic Church, which fell for the first time on an American cardinal, the Italian-born Argentine Jorge Mario Bergoglio, who from the St. Peter’s Plaza in Rome addressed the faithful and evoked his predecessor, Benedict XVI, who resigned weeks ago but is considered Pope Emeritus despite his retirement.

The unexpected new Pope was names after several ballots and two plumes of black smoke. According to media accredited in Rome, the 76-year-old Argentine cardinal will take command of the Vatican under the name of Francis I. He was archbishop of Buenos Aires and is the first Latin American and the first member of the Society of Jesus to lead the Catholic Church, that “will experience as of today an unprecedented situation.”

Bergoglio is considered “an orthodox Jesuit on dogmatic issues but flexible on matters of sexual ethics,” important issues given the demand for reform from the Curia, whose internal problems were reported in the media from the disclosure of documents known as Vatileaks and the crisis around the IOR — Institute for Works of Religion — analyzed in the last assembly of the Church.

It remains to be seen if the new Pope will be the ”pastor that announces the gospel and mercy” as Cardinal Angelo Sodano claimed. It is expected therefore, that he will address the challenges addressed in the days before the conclave, whose members exposed “The need for a strong pope, who can reform the Curia, organize ministries to make them more effective” and resolve leak scandals, plus “promote dialogue with Islam, address the role of women in the Church and the official position on bioethics at a time of global crisis. “

For Argentina, the appointment as Pope of the Archbishop of Buenos Aires may offset the crisis triggered by the defeat of the government’s claim to the Falkland Islands, whose citizens, in a referendum yesterday, expressed the desire to continue being a part of England.

Miguel Iturria Savón

13 March 2013