I waited in a queue of hundreds of mourners marching past the coffin below the chief altar. It was a deadly hot July day. The parish of El Salvador del Mundo in the Cerro municipality of Havana held a funeral wake for the founder of the Christian Liberation Movement Oswaldo Payá, 1952-2012.

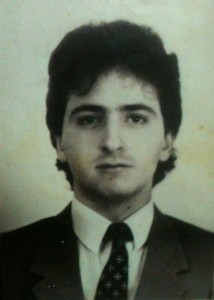

I looked at Payá’s face. His left cheek was bruised. He was lying there – the man whom the Cuban exile accused of adherence to the Castro ideology due to his endeavor to achieve a peaceful transition to democracy “from law to law,” one that would redeem the truth and wouldn’t end up in a mock exchange of one military leader for another, this time wearing a suit and tie. Payá was also criticized by opposition members for defending his convictions too vehemently – a virtue they mistook for authoritarianism. His corpse was now lying there in solitude, so typical of martyrs.

I thought of the young MCL leader, Harold Cepero, who lost his life with Payá. At that moment I felt as if he had looked at me, guiltily, without opening his dead eyes. The heavy curtain of his eyelids has been dropped forever.

I had an overpowering vision inspired in a speech I had just heard, a speech made by Payá’s daughter, Rosa Maria (even younger than the deceased boy). Despite going through great pain, she announced quite calmly to the world that her father had been assassinated after decades of receiving threats and living under constant surveillance. To support her indictment, she also mentioned the text messages sent by the two survivors of the fake “accident” to their home countries, Sweden and Spain.

In my vision, Oswaldo Payá was taken out of the car he was traveling in and was put on an in situ trial by a military tribunal. He was sentenced to death without having a chance to defend himself. The commander-in-chief of the revolution, who had never forgiven Payá for living a free and happy life, thus completed the old personal vendetta against a man who was able to gather more than 25,000 signatures against the regime, a man who spoke fearlessly and without hatred in his heart upon receiving the European Parliament’s Sakharov Prize, a man who had won nomination for the Nobel Peace Prize – the award that Fidel Castro used to covet before he became a senile old man.

Quiet tears ran down my cheeks, and it was impossible to control them. I wouldn’t say I felt sad; I was just devastated. I realized that what started out as a guerrilla movement with barbaric executions without trial long before 1959 has now ended up in an assassination ordered by the government. And businessmen from the free world keep counting and recounting the money they are planning to invest here in the island to become saviors of the last leftist utopia in the world.

It should be noted that the Varela Project of the Christian Liberation Movement, whose idea was to reduce the tyranny of the totalitarian regime by forcing the government to comply with its own laws, is still valid, and no Cuban official will ever gain legitimacy unless the National Assembly of People’s Power complies with the legislative provisions and acknowledges the lawfulness of this public petition, which has been delivered to it in compliance with the Constitution. The Varela Project is Payá’s legacy that will survive both Castro brothers as well as their successor: the capitalism without human rights that they are currently testing in Cuba.

It is quite possible that the crime will go unpunished in terms of the law. Yet, the lives of Harold Cepero and Oswaldo Payá, regardless of whether they were ended as I envisioned or in any another cruel way, have become a kind of a gospel, a heritage shared by all Cubans symbolizing their desire to burn all violence perpetrated by the State on a pile of green uniforms of State Security executioners.

– Orlando Luis Pardo Lazo is a journalist and blogger living in Cuba.

Published in English in The Prague Post

18 July 2013