HAVANA, Cuba, August, www.cubanet.org — Does Raul Castro have a vision for the state? After seven years in office the question bears asking. Perhaps few people thought about it during the previous forty-six years because most observers just assumed that Fidel Castro had a grand plan for the state. But in perspective I do not think so. One can be a political animal yet lack a strategic vision for the country. What is clear, however, is that Fidel Castro did have the political fiber required to constantly to remain in power.

HAVANA, Cuba, August, www.cubanet.org — Does Raul Castro have a vision for the state? After seven years in office the question bears asking. Perhaps few people thought about it during the previous forty-six years because most observers just assumed that Fidel Castro had a grand plan for the state. But in perspective I do not think so. One can be a political animal yet lack a strategic vision for the country. What is clear, however, is that Fidel Castro did have the political fiber required to constantly to remain in power.

He demonstrated the abilities necessary to fuse a founding myth with a sense of opportunity and social control. And everything seemed perfect politically as long as he was able to hide the brutality of his regime, his absolute lack of principles and his incompetence at financial management behind this fusion. But where his lack of vision for the state can be seen is in not having left behind anything serious, such as a legacy, in the three areas where he uprooted the myth: in the social, in values and in the reconquest of the nation. In the end he did not know how to do what politicians with a head for strategy do. He did not know how to reinvent himself.

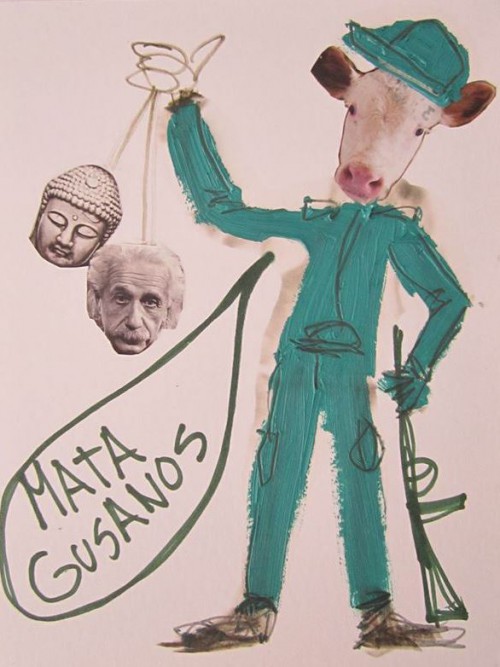

The followers of Castro, the tall one, can say what they want in his defense. However, this only demonstrates that the confusion between expectations and results continues to be fascinating material for two types of study: mythology and clinical psychology. It has nothing to do with reality.

Milk and marabou

Milk and marabou

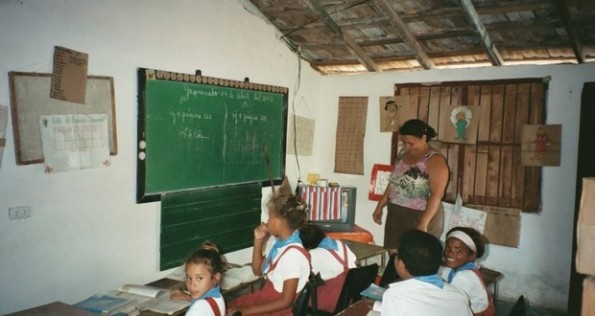

It was hoped that whoever came to power in 2006 would take a healthy dip in reality. Cuba had strayed so far from its revolutionary dreams that this cleansing would be a preliminary step in confronting the task refreshed and with mental clarity. Asians know a thing or two about the relationship between the sauna and the mind. And this appears to be what happened when Raul Castro, in a speech on July 26 of that year in Camaguey, said two trivial words: milk and marabou. They indicated a fresh return to the abandoned land, and an idealized return to the land as metaphor; this after a lofty, fattened regime anchored to the rest of the world only through rhetoric and foreign subsidies.

But strategically the shorter Castro could write a how-to book on disaster. I will not dwell on the long list of his economic adjustments and their social consequences. Much has been well and wisely said about the failure of his so-called economic reforms, notwithstanding the analytical obstinacy of an unwavering group of academics, prominent in the news media, who did (and do) not realize that in terms of economic reform Cuba had (and has) to learn to run, not just move. So I am not interested in judging Raul Castro by his own words. We must measure the man by his results, not by his efforts.

There are two areas I would like to visit in order to analyze what I consider to be a worrying lack of national vision or strategic proposals. One is the port of Mariel and the other is the set of factors facilitating the exodus to what Cubans refer to as la Yuma, meaning everything outside the island, whether it be Brazil, Haiti or the United States itself.

The island as banana republic

The island as banana republic

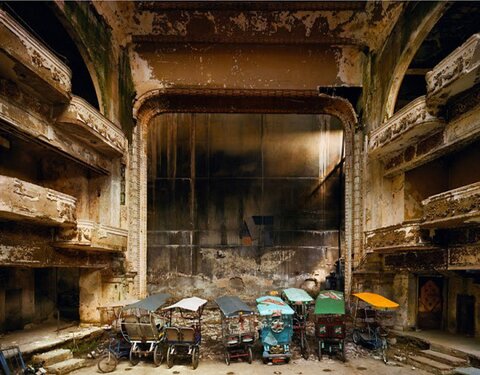

Many see in the construction of the port of Mariel a brilliant strategic move. I see the new port as a step towards turning the island into a banana republic, as we used to be portrayed in the schools of most Central American countries. A social poet, who visited several places in our archipelago to feel its vibration before reflecting them in his poetry, described us at the time as a synthesis that was simultaneously powerful and depressing: Cuba, the ruin and the port.

I find no strategic value in a project that ratifies Cuba as a landlord state, living off of a couple of assembly plants and on being the connecting port-of-call between a super-power (the United States), an emerging power (China) and a jolly secondary power (Brazil). Foregoing the economic possibilities offered by the knowledge economy in favor of one for which we are better prepared — one which depends on the crude economics of the exploited and poorly paid port worker — does not get us much closer to a strategic vision for the state. Nor does a property owner prepared to collect tolls and warehouse fees from all who pass through his ports. But that is indeed what is happening.

Mariel: a circle of illusion

This is because — and here the circle of illusion becomes complete — such a step presupposes two additional elements. One is a deep knowledge of the internal reality of the countries in question. The other is effective control over the temptation of the governmental elite to decide things lest they forget that there is a new port in Cuba called Mariel.

Keep in mind what happened in the Soviet Union in 1989 and in Venezuela in 2013. Having information about what really takes place in countries that affect us economically, and being able to process it, is not the strong point of revolutionary leaders. The former socialist superpower collapsed and Maduro won in spite of losing. China is only interested in money and we have none. And Planalto Palace — the headquarters Dilma Rouseff took over from Lula da Silva — has been trembling lately.

Let us remember that investments in Mariel were being managed by a risk-taking partner, President Lula, who held out the promise to a Brazilian business conglomerate, Odebrecht, of a hypothetical opening by the United States to Cuba. It is as though a fiancée were to put on a wedding dress without knowing for sure that her intended would show up to satisfy her nuptial ambitions. A fiancée who, on top of everything else, behaved as though she did not have to do anything to attract the very specific type of suitor she was after by showing him anything he might possibly find attractive in her.

From subsidies to an economic enclave

There is nothing strategic about turning a subsidized economy into an economic enclave within the confines of old-fashioned capitalism, especially for a country that loudly demands — or rather politely requests — a comprehensive modernization built on the foundations of a knowledge-based economy.

If you are wondering why the government of Raul Castro is involved in this issue, which we know as state strategy, then imagine all that can be done by using Cuba’s potential to assure the structural integrity of the country, guaranteeing a relaxed transition and re-legitimized mandate for successors who lack the pedigree of the mountains we know as the Sierra Maestra.

A new port development provides no insurance in either of these areas. It puts Diaz-Canal in quite a precarious position relative to two interest groups. One is made up of real estate interests tied to unproductive corporations, and the other is made up of citizens excluded from sharing in the pie, which can only grow arithmetically rather than exponentially.

And the exodus to la Yuma? Well, this is where the disconnect between the sense of the treasury and the sense of State is perhaps best revealed. Now that the treasury no longer puts food on the table, we have weakened the possibilities of redefining the State by making an overseas sojourn possible for what the utilitarian language of economics calls human capital. It really surprises me that the emigration reform law has been so widely applauded. After granting fifteen minutes of fame to the restitution of a right that did not have to be taken away, there should have come a serious and sober analysis of its medium and long-term impact on the nation and the country, which are really the same thing.

Living off remittances

Two facts continue to be confused: as an economic reform measure, the migratory reform converts Cuba into the El Salvador of the Caribbean: living off remittances. And as the restitution of a right, it destroys the options to rethink an economic model to export the best young minds of the country, as a country like India has avoided.

The media analysis has blurred the problem, focusing the discussion on superficial political terms. They say that the Cuban government has thrown the ball in the court of the rest of the world, as if it were a tournament which, in reality, doesn’t exist between states — all countries let their own citizens leave and abrogate the right to allow the citizens of other countries to enter — and obscure the principal debate: the fate of a country, aging, losing in a trickle or a torrent its potentially most productive and creative people and, on the other hand, not rebuilding its image as a possible nation.

This the principal problem of our national security. And it only has one origin: The concentration of the political in a single lineage. The philosophers of this matter are right: politics begins beyond the family sofa.

The problem takes on a new light, more dangerous in terms of national security, with an immigration reform targeted to Cubans by the United States, much deeper than that of Raul Castro. The granting of a five-year multiple-entry visas to those who live on the island grants a right foreigners greater than that granted by the Cuban State to its own nationals living inside and outside the country. This is somewhat embarrassing. Cubans from here can freely enter and leave the United States for much longer than Cubans can enter and leave their country of birth without renewing their permit.

Citizens of both countries

One of the results we have, one which I want to focus on, is this: we Cubans have become, in theory, resident citizens of two countries. Cuba is one, you choose the other. This is an issue that goes beyond the transnational nature of our condition — very well analyzed by Haroldo Dilla, a Cuban historian based in the Dominican Republic — because over the long term it weakens the center that serves as the axis to the global nature of citizenship. We Cubans will stay in the same place in an ambivalence that weaken loyalties to a nationality that one now feels and lives anemically. A strange and dangerous situation for a country lacking a sense of solidity.

If the story says that the new U.S. policy serves to promote relations between Cubans and Americans and between Cubans and Cuban Americans, in reality we are moving to a scenario in which relations between Cuban-Americans, in fact, resident on the island, and Cuban-Americans by law, resident in the United States arise and are strengthened; and on the other hand between Americans and Cubans residing on both shores.

All that will be left is an irreducible minority, regardless of their ideological leanings, who will resist nationality in both, taking American or Spanish nationality as strong reference points.

So, we return to the economic and cultural circuit of the United States — in some way we have already entered that of Spain — which we supposedly left more than half a century ago. Not to mention other smaller circuits such as those of Jamaica and Italy.

Surrendering to this reality, hiding behind the anti-imperialist rhetoric of “no one surrenders here,” that keeps obsolete arms oiled and “repaired,” is evidence that the strategy of the State has never accompanied the Castros. Will our paradigm as a nation ever be viable? The question is not rhetorical.

From Cubanet

18 August 2013