Between the “Collectives” and the “Rapid Response Brigades” / Antonio G. Rodiles

State violence has been the Cuban regime’s principle recourse for maintaining power for over 55 years. Beginning with the insurrection against Fulgencio Batista, executions, as a method of punishment, were used relentlessly. Anyone who wanted to show their loyalty had to deliver the coup de grace and take part in executions. A mix of the Communist brutality of Mao’s China and Stalin’s Soviet Union, with doses of the Mexican Revolution.

State violence has been the Cuban regime’s principle recourse for maintaining power for over 55 years. Beginning with the insurrection against Fulgencio Batista, executions, as a method of punishment, were used relentlessly. Anyone who wanted to show their loyalty had to deliver the coup de grace and take part in executions. A mix of the Communist brutality of Mao’s China and Stalin’s Soviet Union, with doses of the Mexican Revolution.

Watching the revolutionary courts, the shouts of “to the wall,” the ruthless political imprisonment, and the continued executions ratified and defended by Ernesto Guevara on the dais of the United Nations itself, instilled a feeling of helplessness within a great part of Cuban society.

The so-called Cuban Revolution has a violent history that it will never break free of because it is part of its nature. The infamous “acts of repudiation” in the ‘80s led to the more frequent use of vigilante groups, known as “rapid response brigades,” who doled out beatings and followed orders with the objective of instilling terror in citizens.

These rapid response brigades have been transformed in content and action according to the circumstances and needs of the regime. In the ‘80s they focused on those Cubans who wanted to leave the country; starting in the ‘90s they used them against human rights defenders; until finally coming to focus on any opponent or activist.

Today, these groups for the most part are made up by paid agents of the Interior Ministry, working surgically to prevent the spread of outbreaks of discontent or free thought within the Cuban population.

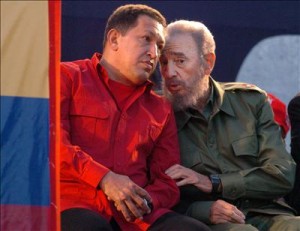

With the coming to power of Hugo Chavez, Fidel Castro’s influence in Venezuela became visible. After the failed coup d’etat against Chavez in April 2002, the Havana regime increased its influence in issues of security and its military presence became increasingly notable. Of course the “rapid response brigades” were also exported from Cuba, now called “Bolivarian militias” or “collectives.” Since then, they have concentrated on arming and preparing them to respond with violence and terror in the face of possible democratic demands.

With the coming to power of Hugo Chavez, Fidel Castro’s influence in Venezuela became visible. After the failed coup d’etat against Chavez in April 2002, the Havana regime increased its influence in issues of security and its military presence became increasingly notable. Of course the “rapid response brigades” were also exported from Cuba, now called “Bolivarian militias” or “collectives.” Since then, they have concentrated on arming and preparing them to respond with violence and terror in the face of possible democratic demands.

The reaction of these violent vigilante to the protests of recent days has made clear that the “collectives,” in coordination with the police forces, have orders to stifle any protest through the excessive use of violence. Terror must be part of the Venezuelan imagination for the full functioning of the regime-under-construction.

The Chavista strategy has been to wrest away democratic spaces, fragment them, and even to dismantle not only democratic institutions, but also civil society organizations. Cuba’s ruling elite knows that a change in Venezuela implies enormous pressure on the island and the certain end of the Castro regime. They know that ordering or driving indiscriminate repression in Venezuela has no legal consequences for them, but rather for the regime in Caracas. They would prefer a thousand times over to cling to the oil no matter it costs, rather than coming to a massive repressive crackdown on the island.

The Venezuelan military should know that Havana will lead them to the brink without the slightest hesitation, but at the same time they should understand that the Castro regime’s codes are not those of the present century — in this century they can often be counterproductive and extremely dangerous.

What is happening in Venezuela should raise serious concerns on the continent because it opens the door to a social dynamic with unpredictable consequences. To create and institutionalize urban vigilante groups, which, to sustain power enjoy perks and impunity, creates an extremely complex scenario in a region where the Rule of Law remains a dream yet to be achieved.

In a region where organized crime, marginalization and poverty are part of the reality, the spread of Cuban methods of social control should set off alarm bells. The violence and cynicism of the Castro regime can still do a lot of damage in Latin America. The Cuban pattern is disastrous. To spread it would undermine the still weak Latin American democracies.

It is essential, therefore, to offer major support and solidarity to the efforts of Venezuelans. Not only is the return of democracy and fundamental rights being decided there, but also being decided is putting the breaks on the introduction of state violence through the use of criminal gangs and urban vigilantes as a norm in the region. Those of us who defend democracy, have a commitment today to Venezuela.

Antonio Rodiles, Havana, 22 February 2014

We Are With You Venezuela / Estado de SATS

Conversation Between an Opponent and a Colonel / Tania Diaz Castro

HAVANA, Cuba, January, cubanet.org — It does not matter whether his name is Armando, Pedro or Juan. What is important is that a few days ago my neighbor the colonel and I found ourselves briefly chatting face to face at the entrance to my house. Such are the oddities of life. He, wore an old coat and a scarf wrapped around his neck, apparently from one of the former Soviet countries. I then wondered where the average senior citizen might be able to buy a coat and scarf to wear during these cold winter months.

HAVANA, Cuba, January, cubanet.org — It does not matter whether his name is Armando, Pedro or Juan. What is important is that a few days ago my neighbor the colonel and I found ourselves briefly chatting face to face at the entrance to my house. Such are the oddities of life. He, wore an old coat and a scarf wrapped around his neck, apparently from one of the former Soviet countries. I then wondered where the average senior citizen might be able to buy a coat and scarf to wear during these cold winter months.

It was the first time we had spoken, though we see each other almost every day. The reason was immediately obvious. It all started with poor quality of the bread, which we buy at the same place on 17th Street in El Roble, a neighborhood in the Santa Fe district of western Havana.

“It’s because they steal the fat that goes in it,” I said.

“The salt too,” said the colonel.

We talked about things that later he might have had reason to regret, but I took the opportunity to encourage this exchange since it is not often that such a spontaneous conversation takes place between a government opponent and a colonel, even a retired one, in the middle of the street on a cold January afternoon.

“I wonder how they will put an end to all this theft,” I said, trying to look naive.

“It’s difficult. The problem has been going on now for a long time,” he said. “In my village back in the 1950s it was unusual to come across a thief. The police were mainly concerned with drunkards and revolutionaries.”

“And there weren’t even that many drunks back then,” I added. “Those were the days.”

We then launched into an analysis of the Cuban experience. He did not defend Raul Castro’s “new economic model” (as I was expecting). Sometimes it even seemed to me he had his doubts, such as when he acknowledged that so far they had yielded no visible results.

When I asked him what he thought the path forward was, he pursed his lips and exclaimed, “I don’t believe in God. But if he exists, he must know what to do.”

I smiled. Was he making a joke? Was it a response born of pathos? I do not know the answer now anymore than I knew then.

“Everything started getting worse when the Soviets threw Stalin overboard and then Gorbachev gave Lenin the coup de grace,” he said. “The Russians wanted to stick us with a bill that was impossible to pay.”

And what about socialism in the 21st century,” I asked. “Does this suggest there will be civil liberties. In Cuba that doesn’t seem likely. Not long ago a government minister said that opposition political parties would never be allowed to take part in elections.”

“You might very well be right,” he said. “Things could change. Everything in life changes. But one must never lose hope, even if it seems there is nothing else that can be done. But if there is one thing that bothers me, it is how much the people are to blame for what is happening.”

“The people are tired,” I said, interrupting him. “They are exhausted. They don’t have hope. They have been living under dictatorship for many years.”

The word “dictatorship” brought him back to his own reality. He frowned, his face tightened and he waved to leave without saying goodbye. Maybe it was the cold evening air in those impassioned times which forced him to see the two of us as we really were: an old man, maybe a little less faithful to the three sprigless stars on the colonel’s uniform he kept in a closet, and an old woman who says what she thinks because she has nothing to hide.

Cubanet, January 31, 2014, Tania Díaz Castro

Jineteras [Hookers] in Cuban Pesos / Reinaldo Emilio Cosano

Havana, Cuba – The colonial authorities never imagined that the covered portals of the buildings and homes of Havana, a mandatory construction to protect pedestrians from the sun, rain and night dew would have another use, also very human.

E.O.F., age 31, counts on the notoriety, although not exclusively, of the portals of Monte street. Or rather Monte and Cienfuegos, the sin corner.

“There is a secret commerce after eleven at night. In the past, you’d find nothing. For a few months pretty women of different ages and races are parked there. They accost the men, inviting them for ’a good time.’ They knew what they were doing there and why men were there at that time. An occupation easy to recognize from the way they walk, the really short skirts, tight clothing, vivid lip colors, eyebrows and eyelashes. Prices are adjusted with few words. They accompany them to a nearby room and pay the rent. In the end, they’re paid. ’A good time…’”

EOF explains a curiosity, “There is no commerce with homosexuals and transvestites with intermediaries. Not from discrimination. They’ve found their half-tolerated space on the Malecon, the Coppelia ice cream parlor, and other places in the capital, although at times the police harass them.

“Now you don’t see them in any of the doorways. It’s the intermediary. He approaches, asking, ’Looking for a girl. They’re good, nice and cheap.’

Five CUC (in domestic currency, one CUC=25 Cuban pesos) for the jinetera [hooker*], one CUC for the intermediary, and another CUC for renting a room for an hour in some solar [as the tenements are called in Havana]. For the most part small, dark, warm, not very clean.

“You go and six or seven women, who a minute ago were chatting, laughing, drinking, between puffs of smoke, stand up. Not for courtesy but intentionally, rubbing their breasts, biting their lips, trying to be chosen. It’s hard to decide, you have to choose fast, pay by the hour, and not overstay your time. Outside two strong guards have the keys and twist the arms of those who try to leave without paying.

“We climb up to the ’barbecue’ [an improvised platform to extend the space]. Generally there are two ’rooms’ separated by a wood partition across which you can hear the whispers and imagine the positions. Not very hygienic rooms. The same sheet all night. Sometimes no water to wash with. No towels, just newspapers. I ask ’Violeta,’ my occasional companion about the chance of catching AIDS. Immediate response, ’Without a condom, nothing!’”

Alejo Carpentier (1904-1980), a Cuban writer and musicologist called Havana “The City of Columns” (1970). The doorways of houses and important commercial establishments were well-lit at dusk on Monte, Reina, Belascoaín, Paseo del Prado and Diez de Octubre streets. So many that it was pure pleasure to walk along the colonnades and contemplate the full shop windows, ruined, in shadows, with many gaps from the sad collapses of our patrimony.

“Why have the jineteras — a word accepted as natural — disappeared from the doorways?”

’Violeta’ answers:

“The police step up the repression streak against prostitution. Sometimes they resolve it with some fulitas (CUCs — hard currency). But if they’re… A….s, not even that. They grab us and we end up in jail. The situation is tough. But many women and men live this.”

“The police step up the repression streak against prostitution. Sometimes they resolve it with some fulitas (CUCs — hard currency). But if they’re… A….s, not even that. They grab us and we end up in jail. The situation is tough. But many women and men live this.”

A report from the Minister of Justice published on the website of Foreign Ministry last October, said that 241 people were prosecuted for the crime of pimping. Of them 224 were found guilty. Formerly prostitute was relegated and controlled by the authorities to the so-called Tolerance Zones, which now permeates the city.

“And what if the police surprise them in the room?”

’Violeta’ replies:

“Every trade has risks. We would test fate saying that we are friends who are celebrating one of our birthdays, and may God protect us!”

*Translator’s note: The word for hooker/prostitute in Cuban Spanish, jinetera, comes from “jockey.”

Cubanet, 31 January 2014, Reinaldo Emilio Cosano Alén

Conduct / Reinaldo Escobar

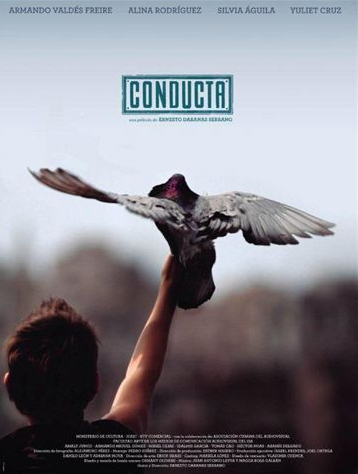

If an imaginary group of Cubans, isolated from all information since 1984, had been shown the movie Conduct today to bring them up to date on reality, they’d have escaped the theater sure that the film falsified the situation: that it was trying to show a pessimistic and counterrevolutionary version of their country.

But that’s not how the people reacted coming out of the theaters, wiping away their tears, their hands red from so much clapping. Especially those Havanans who saw projected on the screen the reality that hits them: their own neighborhood in ruins, the alcoholic neighbor with a child practically abandoned, the lack of ethical values, the police corruption, the discrimination against Cubans from other provinces, the physical misery on every corner, the moral misery in every opportunist.

Fortunately Carmela remained, the retirement-age teacher who, despite having seen her children and grandchildren emigrate, preferred to remain alone on the island, and in her classroom “as long as I can climb the stairs,” because she’s convinced she has the strength to help those kids in need of love and understanding.

Splendid cinematography and excellent editing support a script whose author, Ernesto Daranas, also served as director. Nowhere do the hackneyed topics of Cuban cinema appear: the mockery, the jokes with double meanings, the rain, folkloric touches, sexual exhibitionism and official messages.

But the biggest absence in Conduct is “the New Man,” whom those hypothetical Cubans, asleep or in a coma, conceived even up to the mid-’80s and who they would have expected to see incarnated in this work bringing them up-to-date. The children that those imaginary viewers would insist on finding in the film would be educated children and not those foul-mouthed coarse bullies; the schools would be equipped with laboratories and the houses would appear comfortable and safe.

There would be no dog fights, nor strung out women prostitutes, much less the drama of Carmela facing an attempt to fire her for protecting a student threatened with being sent to a reform school for defending a girl who dared — let’s hear it for audacity! — to place an image of Cuba’s patron saint on the wall of a classroom.

The producers didn’t create an artificial space in the studio in the style of The Truman Show, nor was there some antique store where they found the school desks and blackboards, nor did they make a citadel out of cardboard. The director didn’t have to carefully teach the actors — kids, teenagers or elderly — linguistic models and formulas far from their own personal experiences. Perhaps it was because of this that the audience, after long lines to get into the theaters where Conduct is showing, so identified with it, felt so excited. Because of this and because those present in the movie theaters haven’t spent the last 30 years sleeping, but rather starring in this tragedy.

21 February 2014

The Weekend… 2 of 2 / Luz Escobar

The Weekend… 1 of 2 / Luz Escobar

Conduct, with the “C” of Cuba / Yoani Sanchez

Miguel has earned a lot of money this week. He managed to sell almost one hundred pirated copies of the Cuban movie Conduct. Although the film is showing in several of the country’s theaters, many prefer to see it at home among friends and family. The story of a boy nicknamed Chala and his teacher Carmela is causing a furor and leading to long lines outside the premiere cinemas. It’s been decades since any national production has been so popular or provoked so many opinions.

Miguel has earned a lot of money this week. He managed to sell almost one hundred pirated copies of the Cuban movie Conduct. Although the film is showing in several of the country’s theaters, many prefer to see it at home among friends and family. The story of a boy nicknamed Chala and his teacher Carmela is causing a furor and leading to long lines outside the premiere cinemas. It’s been decades since any national production has been so popular or provoked so many opinions.

Why is the latest creation of director Ernesto Daranas becoming such a social phenomenon? The answer transcends artistic questions to delve into the depth of his dreams. While it is clearly told with excellent cinematography and superb acting, its the realism of the script that is the greatest achievement of this film. The movie generates an immediate rapport with the audience, reflecting their own lives as if reflected in a mirror.

In the dark theaters, facing the screen, the spectators applaud, scream and cry. The moments of greatest emotion from the house seats coincide with the politically most critical speeches. “No more years than those who govern us,” answers the teacher Carmela when they want her to retire because she’s spent too much time in the teaching profession; an ovation of support runs through the theater at that instant. The semi-darkness exacerbates the audacity and complicity.

The “Conduct phenomenon” is explained by its ability to reflect the existence of many Cubans. But it goes far beyond a simple realistic portrait, to become an x-ray that lays bare the bones. A Cuba where there is hardly any moral framework left for a child in this environment light-years away from the ideal claimed by the official media. Barely twelve, Chala supports his alcoholic mother with what he earns from illegal dog fights, inhabiting a harsh unjust city, impoverished to the point of tears.

It’s not the first time Cuban cinema has shown the tough side of reality. The film Strawberry and Chocolate (1993) paved the way for social criticism, particularly with regards the discrimination against homosexuals and artistic censorship. The cost of its daring was high, because it had to wait twenty years to be shown on national TV. Alice in Wonderland (1991) faced a worse fate, with the political police filling the theaters where it was projected, and party militants screaming insults at the screen. Conduct has arrived in at different juncture.

The spread of new technologies has allowed many filmmakers to find ways to make their projects. Critical, acerbic and rebellious scripts have seen the light in the last five years because they have no need for the approval and resources from the Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry (ICAIC ). This proliferation of shorts, documentaries, and independent films has been a very favorable situation for Ernesto Daranas’ filmstrip. The censors know that it’s not worth the trouble to veto such a movie on the State circuits. It would run through the illegal networks like wildfire.

A brief conversation outside the Yara cinema exposed the controversy this story unleashed. “There are a lot of people who live better than Chala, that’s true, but there are others who live much worse,” said a man in his sixties. A young woman responded that she wondered if the director ”exaggerated the squalor of the situations shown.” Another girl joined the debate to say, “You say this because you live in Miramar, where these things don’t happen. ”

On Tuesday night, the ruling party journalist Randy Alonso also joined the line to see the movie in the final showing of the day. Behind him giggles and comments were heard — “So what’s he doing here?” — given that his face is associated with uncritical journalism, a sycophant of power. Once inside the theater, those who sat near him did not see him join the chorus of shouts of support. With every minute that passed, he seemed to sink more deeply into his seat, not wanting to be noticed. What he was seeing on the screen was the exact opposite of what he explains on his boring Roundtable show.

So it is that Conduct was able to gather in the same room the fabricators of the myth and those burdened by it. After the projector is turned off, the doors open and the viewers exit to reality similar to the script, but one where they can no longer express themselves under the protection of the shadows. Chala waits for them on every corner.

21 February 2014

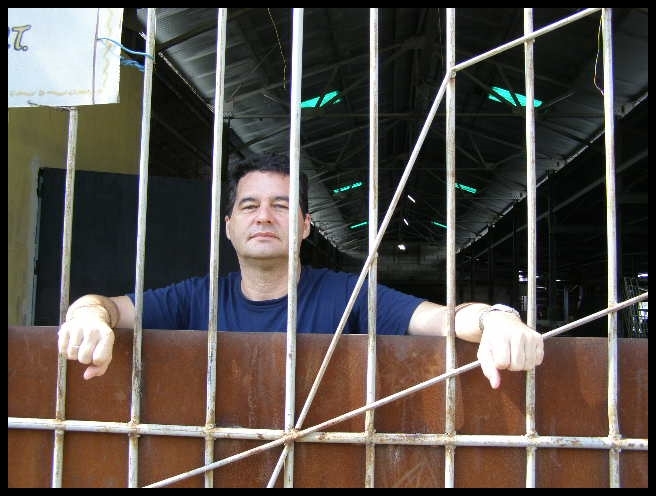

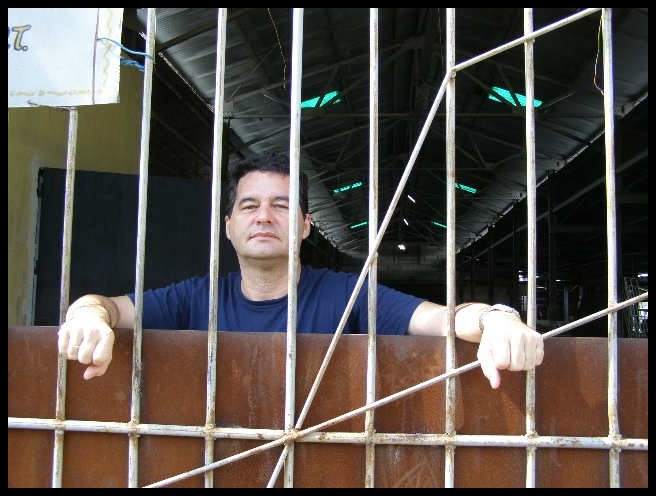

Cuba and Its Parts in Conflict / Angel Santiesteban

We know that in more than a half century of command, the only thing that has interested the Castro brothers is to keep their damn power. For that they have submerged the nation in profound poverty. In order to maintain their prolonged rule, they have converted the country into a state of terror.

They have filled the prisons with young people who, not having another option, have preferred to become delinquents rather than becoming submerged in the profound, generalized economic crisis. Also the professionals, after pursuing advanced degrees and becoming professionals who would be in high demand in any other country, are obligated to commit crimes of embezzlement. The lucky ones have found a way of leaving the country definitively, or by employment contracts between the states in question, and with meager pay, which helps them to moderate their miserable lives.

Another part keeps hoping to emigrate, and while that wait goes by, they repress their longing to think, criticize, demand better, because they fear reprisals from the political police for daring to dissent from the government program, and they survive on remittances received from the exterior.

The minority remain, those who don’t have even a remote possibility of emigrating or receiving remittances, and although they may also dissent like the rest, they have no other option but to cling to the structures of power to receive the inferior surplus that they let escape for those who get close, which is barely sufficient to breathe and to survive.

Power is maintained thanks to the blackmail of this minority, which they use as a repressive force. The so-called “white collar” crimes are very common, because they toil like prisoners, in economic control or directing construction works.

Ángel Santiesteban-Prats

Lawton Prison Settlement, January 2014

Please follow the link and sign the petition to have Angel Santiesteban declared a prisoner of conscience by Amnesty International.

Translated by Regina Anavy

15 February 2014

Concerned in Villa Clara About What Is Happening in Venezuela / Alex Reinaldo Perez

SANTA CLARA, Cuba – The demonstrations by students and opponents of President Nicolas Maduro in Venezuela are the news of the moment.

SANTA CLARA, Cuba – The demonstrations by students and opponents of President Nicolas Maduro in Venezuela are the news of the moment.

Countless media worldwide are focused on the events. The web is full of videos, images, writing. We Cubans are not unexposed to this; although we only see and hear what the censored media broadcasts. Remember, we don’t even have free access to the Internet.

While the media on the island catalogs the events as “an intended coup against Nicolas Maduro planned from abroad,” thousands of Cuban families are desperate, fearing for their family members who are in Venezuela. According to official figures, 30,000 Cubans are working in this country.

For the relatives of the Cubans “on a mission” in Venezuela, it’s nerve wracking. They think the national TV reports of Cubans carrying on with their usual activities are false. “Venezuela is burning,” is the phrase that runs from mouth to mouth in this province.

Concern among the population is striking. People know that the fall of Maduro and Chavismo could strongly affect the daily lives of Cubans.

Loreto del Sol Pérez remembers that during the so-called “Special Period” in the 1990s, high-ranking officials weren’t affected: they monopolized the food supply, fuel, basic necessities, and became the black market suppliers.

Mrs. Omara Diaz says that if the Special Period returns, she won’t be taken by surprise. To the extent her pension reaches, she will buy a few candles for the blackouts. She also commented that she’s looking for the oven her son concocted during the Special Period for cooking with sawdust.

Rafael Villavicencio, retired from the Interior Ministry, said that the events in Venezuela are caused by the government of the United States of America. He added that they were “mercenary actions to prevent the integration of Latin American countries, where Venezuela plays a super important role.”

Meanwhile, Mario Ruano, a retired professor of Marxism and History concluded that the “coup attempt” is a response by Barack Obama to the “successful” summit of the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC), recently held in Havana.

According to the dissident Guillermo del Sol Pérez, Venezuelans taking to street in demonstrations have the view that Maduro wants to implement the regime of the Castro brothers in the land of Simon Bolivar.

The truth is that Venezuela is currently uncertain territory. Cubans are on the lookout for what happens there. When things calm down most of us, ordinary Cubans, still won’t know what’s going on.

Some are asking God not to let Nicolas Maduro cede the reins of Venezuela because they imagine what awaits us if that happens.

Simply that, for elemental survival.

Cubanet, 21 February 2014, Alex Reinaldo Perez

From the Pen of Bradbury, Čapek, Hurtado and Chaviano / Yoani Sanchez

Among the most precious possessions of my childhood was a collection of science fiction books. Those pages filled long hours of my life, allowing me to know other worlds and to escape — at will — the flat reality. My sister liked the tales of far off planets, space ships and extraterrestrial civilizations. I preferred the possible fantasies, that left me with the feeling that at any moment something could happen: Time travel, genetics-manipulating scientists and creatures rescued from yesterday were my favorites.

From the pens of Karel Čapek, Isaac Asimov, Daína Chaviano, Stanislaw Lem and Oscar Hurtado, my adolescence was a time enlivened with robots, humanoids, fairies, flying saucers, and remote galaxies. Several compilations of the genre had been published in those years, in editions with yellowed pages and cramped typography. On our bookshelf there was a place of honor for The Martian Chronicles, Quick Freeze and The Call of Cthulhu, the great stories of Ray Bradbury and the novel The Space Merchants. Those books for us were like doors to another dimension.

The 23rd Havana International Bookf Fair has brought a selection of science fiction authors. On the Cuban side José Miguel Sánchez (Yoss) stands out, while the foreign author of greatest note is the Russian Serguei Lukianenko. Absent, however, are the great titles of the last decade in a genre that keeps evolving and attracting readers. The reason for such a failure is the lack of many local publishers’ economic capacity to buy the copyrights from foreign writers. There is also a certain underestimation of the genre, which has failed to find a place in the annual plans of what is printed and promoted.

20 February 2014

Details of Insularity / Angel Santiesteban

Historically, we Cubans have been separated politically, and although diversity is healthy for free thought and democracy, we have been marked by the extreme of what we wish to attain and defended it at all costs.

José Martí never was understood by those upper military leaders who accompanied him, and his death, in a certain way, was caused by them. Before, Carlos Manuel de Céspedes also had his political enemies inside the mambisa rebels, until he was removed as the President of the Republic in Arms, and replaced with Salvador Cisneros Betancourt; then they left him alone and without protection in San Lorenzo, and there is a version of someone confessing at some moment that it was a betrayal of the high command of the insurrection.

Political struggle has been a constant in Cuban history; inequality existed even within the same parties. The day that we learn to listen and understand one another will be the day we have the force to change our society. But first we have to start with ourselves, an unfinished subject for all Cubans. Until then, unity is till a pending issue, and the freedom of Cuba is compromised.

Ángel Santiesteban-Prats

Lawton Prison Settlement, February 2014

Please follow the link to sign the petition to have the dissident Angel Santiesteban declared a prisoner of conscience by Amnesty International.

Translated by Regina Anavy

From the Banana Fair to the Un-Fair / Yoani Sanchez

When the days are cloudy Havana Bay takes on a strange, gray tint. When viewed from the Fortress of San Carlos de la Cabaña, the city looks like a faded postcard. Yesterday morning the public opening of the International Book Fair perfectly coincided with a winter’s day. So the colorful posters announcing the titles and the authors to be honored flapped in a chill February breeze. A brisk reading many appreciated.

When the days are cloudy Havana Bay takes on a strange, gray tint. When viewed from the Fortress of San Carlos de la Cabaña, the city looks like a faded postcard. Yesterday morning the public opening of the International Book Fair perfectly coincided with a winter’s day. So the colorful posters announcing the titles and the authors to be honored flapped in a chill February breeze. A brisk reading many appreciated.

Among the main attractions of this Fair is the site itself. The esplanade of a colonial military fort and its rounded galleries gives a vintage touch to the literary event. Parents take take the opportunity to bring their children to frolic among the old cannons and the walls of stone. The gastronomic offerings, the sale of handicrafts, and other associated choices, come to play a bigger role than the books.

This twenty-third edition of the fair confirms the deteriorating trend in Cuban publishing. Although the official media announced two million copies and some 400 invited guests, the decline of our main cultural event is obvious. The reasons for this loss of brightness range from the purely commercial to the ideological. Such that the Fair, approaching its quarter century, is aging and urgently in need of a reevaluation.

A celebration of books and reading where too much is missing. The long list of what is censored for political considerations, among which are numerous Cuban exiles. Missing names like Guillermo Cabrera Infante, Reinaldo Arenas, Jesus Jesús Díaz, Daína Chaviano or Abilio Estévez. The silence also extends to writers of other nationalities like the Nobel laureate Mario Vargas Llosa. Ideology still stands as the main criterion when sending out invitations.

The limited economic capacity to acquire copyrights from living international figures still writing impoverishes our publishing. There is a marked tendency to publish the classics over and over, which clearly are must-reads, but shouldn’t constitute the only option. Many shelves in this Book Fair seem to come from the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, rather than from today.

The scarcity of contemporary titles is especially dramatic in the children’s options. Every year the youngest readers can choose only local authors, or names such as Emilio Salgari, Jules Verne and the Brothers Grimm. The greatest hits of the fantastic literature for children and teens in the last decades, have not been present on the national circuit. Harry Potter was never issued by a Cuban publisher.

A book fair should be a site to make contacts, close deals, get to know new authors who will be published later. This function of serving as a meeting point doesn’t exist at the Havana Book Fair. It lost, or never had, the character of a showcase not only for an audience that wants to buy or browse, but for entrepreneurs , directors or cultural promoters of the publishing world.

How many agreements are closed during the two weeks of the event? What is the total amount of contracts signed? The day we know the answers to those questions we will be able to see on the Fair’s heart monitor whether it’s a straight line and a beep that confirms it’s over.

Ideology also influences the selection of the guest country, whose offerings in recent years have been turned into more of a showcase for the ruling party than a literary exposition. On this occasion the announced highlight of the Fair was the presentation of the book “From Banana Republic to Non-Republic,” written by Ecuador’s president Rafael Correa. The cancellation of the South American dignitary’s trip “for work-related reasons,” was not properly announce. The Fair was already in a free fall since its opening, where off-the-cuff speeches tried to cover the absence of the missing president.

Still, the fairgrounds have been filled and will continue to be filled in the coming days. People will buy thousands of books and stand in long lines to get the most attractive titles. Because the number of visitors doesn’t reflect the quality of the fair, but rather the publishing wilderness that surrounds us the rest of the year. Parents will watch their kids play between the walls of what was once a prison and also the scene of summary executions. The Havana that presents itself from La Cabaña in this gray winter is a strange and beautiful sight.

The Un-Fair has begun.

15 February 2014, from Yoani’s “Cuba Libre” blog in El Pais newspaper