The miter leans slightly with the rhythm of the ritual, leaving his back exposed to the stone face of José Martí. On the table of the Mass, the chalice rests and reflects from its golden surface a relief of Che Guevara mounted on the facade of the Ministry of the Interior. Benedict XVI officiates mass in the Plaza of the Revolution, and the whole scene could not be more contradictory, more unreal.

In the red heart of red Cuba, the Lord’s Prayer is heard, and a few yards from Raúl Castro’s office, a multitude responds with an “amen” instead of the traditional “fatherland or death.” In the street in front of the altar, ordered reticles contain those attending the Catholic liturgy. When the television cameras pan the scene it’s clear many of them don’t know how to pray or how to cross themselves.

There is also a VIP area filled with the members of a government that defines itself as Marxist and atheist. The Communist Party leaders aren’t wearing olive-green but rather suits and ties, but even so they clash with the white clothes of the many believers and the red of the cardinals. Wednesday, March 8 has barely dawned and the island seems exhausted by the two days St. Peter’s successor has already spent among us.

The visit began in the east of the country. After the jubilant throngs that greeted him in Mexico, the Pope found a surprisingly orderly people here, lined up along the road between the airport and the city of Santiago de Cuba. The crowd carried no posters nor were shouts of joy heard; it was simply a gentle stream of people with little flags waving in their hands. An image perfectly suited to the adjectives “educated, composed and organized” which the newspaper Granma had used a few days before to describe the people who would wait for Benedict XVI.

Also, with sufficient lead time, schools and workplaces received their marching orders. “We must show respect to His Holiness, believers as well as non-believers. No one can miss Mass,” they were warned at meetings called by union, party and student leaders for this purpose.

Knowing the euphemisms that rule Cuban official language, reading these marching orders was clear: no enthusiasm and no spontaneity; anything that departs from the program will be punished. In some companies, whose employees received a bonus in convertible currency, the message was even more direct: those who don’t attend will lose the hard currency cash stimulus. Which explains, in part, why so many atheists and materialists showed up at dawn in the plazas on the days when the Supreme Pontiff celebrated Catholic worship.

Cachita

The preparations for the papal visit had started months earlier, when it was announced that His Holiness would visit us for the celebration of the 400th anniversary of the discovery of the image of the Virgin of the Caridad del Cobre. Our patron, popularly known as Cachita, was found in the Bay of Nipe in the early 17th century. Two men and a teenager, all three named Juan, found her floating in the water.

So Cachita, rescued from the waves by those arms, became the Mary of a people who, centuries later, would launch themselves into the Straits of Florida on rafts, doors converted into boats, and trucks made watertight so they would float. The Mambisa Virgin, who was also with those who demanded Cuba’s independence from Spain at the point of machetes, now adorns the altars of our compatriots scattered across the globe. She has her shrine in Miami, as she has her sanctuary in Santiago.

Cachita was the first rafter, only did she not escape, she arrived, not wanting to reach other horizons but to stay with us forever. And in honor of this “traveler of the faith” Joseph Ratzinger also came to Cuba. To pray in a temple full of offerings, known as El Cobre, for its proximity to copper deposits. In the entrance hall of the busy church — the Chapel of Miracle — is a varied collection: locks of hair dedicated by girls planning to marry a foreigner alternate with booties from babies written off by doctors but who managed to survive. Bracelets from the 26th of July Movement left there by rebels who once wore scapulars, but ended up banning them. In one corner a card recalls the dissidents imprisoned during the Black Spring of 2003. Only under Cachita’s cloak can such plurality coexist.

Fidel Castro’s mother herself offered this Virgin the silhouette of her son sculpted in gold so that he would survive the rigors of the Sierra Maestra. Ernest Hemingway’s Nobel Prize lies side-by-side with several military orders that belonged to the Fulgencio Batista’s soldiers and officials. All the elements of the national melting pot come together at the feet of Cachita, under the protection of the crown that adorns her head.

Benedict XVI also brought his own gift for our patron: The Golden Rose, one of the highest decorations awarded by the Catholic Church. And with each day the offerings grow, as five hundred people cross the threshold of that temple daily,; on the weekends the numbers double. Some from devotion, others out of curiosity. Who knows?

Joseph Ratzinger entered this sanctuary one warm March morning, surrounded by the faithful. On the steep road leading there he didn’t see any of the vendors who normally offer wood carvings of the Virgin of Charity. Nor were there the traveling sellers or flowers, candles and little pebbles speckled with copper.

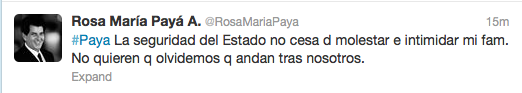

Also missing were the Ladies in White, who every Sunday make a pilgrimage to the temple of our Patron Saint. They were there for several days before being warned by State Security to stay away. Several of them were subject to house arrest, while others fared worse, ending up in one of the area’s jail cells.

Like someone who cleans the house to receive an important guest, the Cuban government had decided to sweep all the inconvenient citizens under the carpet. To achieve that, they triggered the strongest campaign of repression of recent years.

From atheism to faith

In a population that has had to wear so many masks to circumvent the controls, it is difficult to distinguish between those who really believe in God and those who don’t. Among those who showed a vertical materialism thirty years ago, today are many devout and mystics. However, despite this emergence of religiosity, we remain a people of few practitioners, perhaps for lack of perseverance, or perhaps because freedom from worship, once interrupted, delays its return in all its aspects.

Many who feigned being anti-religious when it was an ideological sin to have a picture of the Sacred Heart of Jesus in your home, are now confessed Santeros, Jehovah’s Witnesses, or Seventh Day Adventists. Cubans coming out run through an odd and surprising route, through agnosticism to faith, from doubt to belief. Crucifixes are no longer hidden under shirts, and altars to saints are in plain view in the living rooms of thousands of homes.

The custom of baptizing children has returned after several generations that never received this sacrament. Church weddings are back in fashion, and it’s common in hospitals to see the sacrament of last rites. Catechism classes are filled with children whose parents had to learn in school that “religion is the opium of the people.” National history seems to have closed a cycle of guns to begin another of rosaries.

And not only religion, the Church as an institution has gained ground in our society in recent years. Among other achievements is the possibility of opening a new seminary to train priests. Catholic masses are broadcast on national television on certain important dates and even the political discourse has cast aside its old anti-religious slogans. December 25 has been a holiday for fourteen years, an accomplishment of John Paul II, and now Benedict XVI has given us the first Good Friday off in several decades.

The papal visit of March 2012 was also focused on strengthening the spaces already recovered and extending pastoral action to other areas of society. One of the long deferred dreams of the Cuban archdiocese is to be able to teach Christian ethics in the Island’s schools. Cardinal Jaime Ortega y Alamino has been playing a decisive role in these present conquests and their possible future expansion. His personal history includes a stay, in the mid-sixties, in the so-called Military Units in Aid of Production (UMAP). Under these initials were hidden forced labor camps surrounded by barbed wire where homosexuals, Catholics, Jehovah’s Witnesses and other politically incorrect “elements” were interned. Perhaps from having lived there the Archbishop of Havana knows what the Cuban government is capable of against those who oppose it.

Ortega y Alamino led the controversial negotiations between Church and State that culminated in the release of the prisoners of the Black Spring. Applauded by many and criticized by many others, those conversations were notable for the absence of various stakeholders who had been peacefully demanding the release of those dissidents and independent journalists.

The Ladies in White — wives, mothers, sisters and daughters of the prisoners — were excluded from the table where it was agreed to draw back those locks and, for many of the incarcerated, exchange the bars for departure into exile. The Church emerged strengthened by its role as mediator, but perhaps not even its ancient wisdom allowed it to measure the enormous responsibility it had assumed.

In a country where all the roads by which civil society can make demands or question the government have been cut off, any small path that opens in that direction is immediately crammed with requests. The effects of the Catholic Church assuming political leadership at that moment did not fail to be felt.

On March 13, in a Havana temple consecrated to the Virgin of Charity of Cobre, a group of thirteen people gathered, asking that a list of demands be delivered to the Pope. The list ranged from the authorization to form political parties to respect for economic freedoms. They refused to leave when the mass ended, and demanded a chance to speak with some representative from the Church hierarchy.

After three days without anyone offering them food, an unarmed commando moved in and removed the occupants by force. Undertaken with the consent of Cardinal Jaime Ortega, this eviction maneuver sparked a deep discontent among other activists, even those who had expressed their disagreement with the tactic of breaking into a church.

One unfortunate note published by the Havana Archdiocese in the Communist Party’s Granma newspaper implied that the official and ecclesiastical discourses could once again be almost identical in certain situations. The incident was broken up in a misguided way before the arrival of Benedict XVI, so its political cost will linger for a long time. Cachita’s golden mantle did not serve, on this occasion, to protect all her children.

Wojtyla vs. Ratzinger

Parallel with citizen disconnect, another shadow cast over the arrival of His Holiness was the luminous trail left by his predecessor. The Polish Pope, Karol Wojtyle, traveled to Cuba in January 1998 and so was the first Pope to arrive in our land. We experienced, then, moments of hope and doubt. We’d recently emerged from the hardest years of the so-called Special Period, with its economic crises and endless blackouts. The Berlin Wall had fallen nearly a decade earlier, partly due to the influence of this Traveler of the Gospel on events taking place in Poland and other Eastern European countries.

John Paul II came preceded by the thunder of a political bloc that had disarmed while Fidel Castro’s government put into practice small and controlled economic reforms to avoid a collapse. The man who had been educated in Jesuit schools and later renounced the faith waited at the foot of the stairs for the old anti-communist born in Wadowice.

Seldom has a welcoming ceremony had so many explicit and subliminal messages as those that would be read on that January 21, 1998 at José Martí Airport. Face to face were the Guerrilla and the Pastor, the atheist and the pontiff, he who imposed the writings of Marx in the schools, and he who spread the Holy Bible.

John Paul II had ventured a phrase that would not come to pass in the nearly fifteen years between one papal visit and another:

“Let Cuba open itself to the world and let the world open itself to Cuba.”

These were his words but insularity — more political than physical — continued to mark the national direction. His presence in several Cuban provinces was met by an enthusiasm that his successor couldn’t even begin to equal. One of the popular signs of the disgust that met Benedict XVI was the absence of jokes about him. In a festive people who laugh even in the midst of great material scarcity, the jokes and funny stories that greeted the coming of Karol Wojtyla could have filled a book.

But in March of 2012 Joseph Ratzinger found us more serious, more tired. Pepito, the eternal mischievous urchin of so many popular stories, didn’t deign to appear on this occasion. As one day faith abandoned so many Cubans, now it was sarcasm that had taken its leave. All we managed to come up with were a few word plays, as in Spanish the word “papa” means both pope and potato — that tuber so missing from our plates. An elementary and trite play on words between the resident of the Vatican and this savory bite that has disappeared from our forks: “Instead of habemus papam, what we want is potato,” Cuban housewives joked.

Fourteen years later it was clear we were no longer the same, but neither was the pope. The Commander-in-Chief did not wait for him at the airport, rather the red carpet was watched over by his little brother, Raul Castro. The heir to the triple tiara was received by the Cuban heir to the throne.

In his welcoming speech, the General President said that the country was absorbed in a process of transformation. As if the ancient memory of the Church could forget that similar phrases had been pronounced before the previous pope. If the hosts feared that Benedict XVI might emit criticisms about the management of the Communist Party on Cuban soil, real life calmed them. His public speeches were centered on pastoral themes and the boldest phrase that came out of his mouth was to assure us that “Cuba is looking to the future.” Beyond that, there was incense in abundance while social and political references were scarce.

There was no time on the papal agenda to meet with the outlawed voices of civil society. Well in advance, the Ladies in White had solicited at least one minute to tell His Holiness of this other Cuba that the official side never includes in its conversations. There is no one better than they to make such a demand.

Every Sunday for the last nine years dozens of these women have attended mass at Santa Rita, patron of impossible causes, to pray for their imprisoned family members. The peaceful women’s movement they represent has spread to seven provinces and, although many of the Ladies have accompanied their husbands into exile, there are now more than one hundred members on the Island.

Cuban Cardinal Jaime Ortega’s failure to include the Ladies in White in his negotiations with the Cuban authorities has been strongly criticized, as these women have — without question — the merit of having put their lives in danger in the streets, before a government that penalizes political opposition and free expression with long prison sentences. If the cardinal and the president had opened this space, there would have been faith that the pope would have met with them.

But Vatican spokesman Federico Lombardi, already on Cuban soil, said that Benedict’s schedule was too tight for a meeting with the dissidence or other civic groups. But he could dedicate half an hour of his scarce time to the ex-president Fidel Castro, with whom he met at the Apostolic Nunciature in Havana.

A frail old man, accompanied by several of his children and his wife, spoke with the man who, in his day, was the prefect of the Congregation of the Doctrine of Faith. This meeting irredeemably tilted the papal visit to the side of officialdom. In Mexico he had refused to cross words with the victims of clerical child abuse, and in Cuba he abstained from an exchange with the victims of governmental abuse.

The pope yes, the citizens no

Benedict had used up all the controversy his stay in Cuba would raise days before he landed at Antonio Maceo Airport. He addressed the Island’s model in very strong words while on his plane en route to Mexico. “Communism is no longer working in Cuba,” he decreed, in what seemed to be the preamble to a visit marked by tensions between Catholic doctrine and a government that declares itself — even today — Marxist-Leninist. But as the papal delegation approached our skies, the discourse was moderated.

Although the national press did not publish these criticisms from His Holiness, most people learned of them thanks to the illegal information networks and the persecuted satellite dishes that capture channels from Florida. Everyone knew, but few made their knowledge public. In schools and workplaces it was insistently repeated that attendance at the Pope’s Mass was an imperative, in the same tone used to announce the May Day parade.

Despite the controls deployed, in the middle of the plaza of Santiago de Cuba a man named Andres Carrion shouted, “Down with communism!” His words echoed in the morning air above the psalms and prayers, even reaching the ears of those closest to the pope. Immediately two plainclothes police evacuated the daring activist who had made a mockery of all the fences.

Once Carrion was beyond the area visible from altar, a man wearing the insignia of the Red Cross hit him in the face and brought a stretcher down on his head. Before the astonished eyes of the foreign press and the opportunistic lenses of several cameras, the scene explained very well how the circles of vigilance were set up around that gathered flock. With police camouflaged as the faithful, as nurses, as lighting technicians. If anyone expected to see a booted soldier with a gun on his belt repress the indignation, what happened would have confused and affected them even more.

The image of that individual, supposedly there to provide first aid, slapping a handcuffed man and beating him with what should have been emergency equipment, provoked the most notorious scandal of the papal journey. The report of what happened reached the ears of the International Red Cross, which demanded an investigation of the facts. Their Cuban spokesperson, several days later, issued a note of apology without specifying the identity of the aggressor.

The short video showing the beating has been seen by millions of Cubans, although the official press never referred to what happened. People must know that Andres Carrion will be charged with public disorder and it has also leaked out that the Vatican entourage intervened to avoid the the application of a very severe penalty.

Perhaps this intervention was motivated by what the Pope had said about Communism before coming to Cuba and what Andres Carrion had chosen to shout in the middle of the plaza. One of them was received with honors after asserting that a system wasn’t working, and the other was locked up and expected to be tried for his actions. Dramatic paradoxes of who and where.

The truth is that the Cuban government’s meticulously planned script for the three-day visit suffered an irreversible setback from one man’s scream, a sobering surprise.

State of emergency… undeclared

To prevent something like what, in fact, happened, innumerable measures — including the most excessive — were taken ahead of time. Throughout all of Cuba hundreds of people were victims of an intensive crackdown during the last week of March.

The Commission on Human Rights and National Reconciliation was able to account for more than four hundred activists taken to police stations or subject to house arrest. The scope and effectiveness of this raid, popularly dubbed the “Vow of Silence,” betrayed its meticulous preparation weeks and months in advance.

Amid the hardships we live with, a repressive deployment of these proportions must have exhausted the national coffers and compromised a share of the resources urgently needed for other sectors.

There are those who say the Pope’s stay among us served as a dress rehearsal for the enforcement mechanisms being made ready for “X-Day,” as the day Fidel Castro’s death is announced has come to be called. And for this, everything will be brought to bear. At least we now know how the first twenty-four hours will pass after the “Great Death”: dissidents behind bars, communications cut, eyes lurking around every corner.

Transportation was virtually paralyzed hours before the Alitalia plane landed and Internet access was cut in schools and workplaces a week in advance. The mobile phone company, Cubacel, became an accomplice, cutting the lines of any potentially “dangerous” users. Even the black market experienced anxious moments with the excessive number of police in the streets. The country was under an undeclared state of emergency.

By the time His Holiness spoke at the Plaza of the Revolution in Havana, filled with believers and non-believers, he had probably already heard of the ideological purge that had rounded up numerous sheep from his flock. Why didn’t he allude to them in his homily? What was the reason for his not pronouncing a few words during his farewell at the airport as a reminder of those who were prevented from approaching his entourage?

One of the detainees of those days tells how they took him to a cell east of the capital, with boarded-up windows. The timing of his arrest, on a public street several hours before the Pope landed in Havana, seemed like something from the script of a bad action movie. In the cell where they held him he found three other opponents who were arrested when they went to a police station to inquire about the whereabouts of a missing colleague.

Through a small hole that opened onto the street he spent the night shouting telephone numbers so that some passerby might call his family, because they denied him the right to make a single phone call. Through the gap he just managed to see the feet of kids playing baseball, the shoes of old people walking to the bodega, and skinny legs of the dogs.

All night he repeated the same digits over and over until he had no more voice to continue. He still doesn’t know who contacted his friends and family, but when he was released they were already aware of his arrest. Perhaps a stranger heard those numbers coming from a small hole flush with the sidewalk and miraculously decided to act as the messenger of such an urgent errand.

Several weeks after Benedict XVI arrived on our Island, the phones still weren’t working and civic activists remained in detention. Like that prisoner in the boarded-up cell, many Cubans are still waiting to unravel the method, the mechanism, through which they can let the Supreme Pontiff know what happened behind the scenes of his visit.

From this side of a closed shutter, within a guarded cell, or in a plaza occupied by State Security, there can always be a small hole through which to send a message. Do they hear it on the other side? Does the papal mantle reach, this time, to protect all of us?

May 2012