I wish it were true that this is a city where the high-life is picking up, as promised in the ads for the book Havana Libre along with some happy photos posted, in advance, on the internet, including the Cubancentric comments against its author: the New York photographer Michael Dweck.

I wish there was, indeed, a Havana with “a creative class in a society without classes,” a glamor in the time of cholera that doesn’t seemed forced for the camera, PMM* that doesn’t parody PM** (the cackling laugh as a framework to put make-up on the metallic grimace of the late nights).

Hopefully this sample is turning out to be the least offensive, the spit of luxury in the big dirty face of the Cuban proletariat.

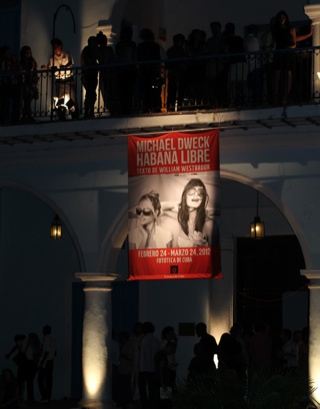

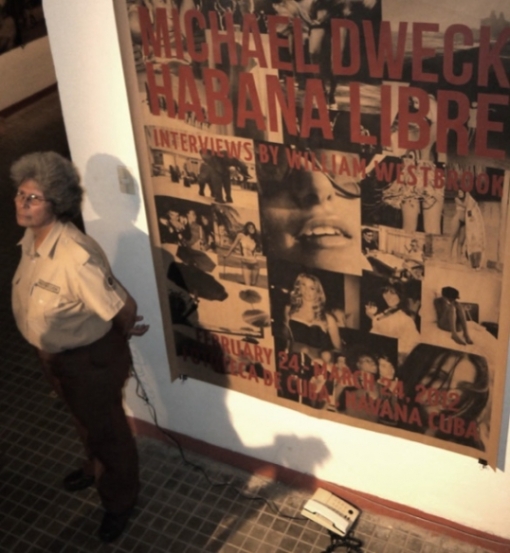

But no, that’s nothing. Rather, the Michael Dweck: Habana Libre exposition, open to the public for a month from 24 February at the Photo Library of Cuba (Mercaderes Street # 307), is excessively correct. A diary of a neutral trip (three years of work and paperwork). From an imitative Malecon to a skateboard park, from the thongs of the Tropicana to the Clubs on the little western beaches, from the Juanes concert in the Plaza to a hotel bedroom that refers to the usual place of our “photos of 15” (very soon they will get naked and their prudish parents won’t even be scandalized). Permitted provocation is not provocation: it’s barely the curriculum vitae of the guy, “one of the first living American photographers to exhibit in Cuba.”

Even the classics of the epic period of the Revolution dared to portray a little more in private, in terms of entertainment and nudity.

So, we are under the warm gaze of a Re-discoverer of the Island, one of those opportune chroniclers who puts us squarely in Western modernity or, still more profitable, who updates us before certain scholarship of Americana (academically: The Cuban Way of Life?).

Half of my colleagues were portrayed by Michael Dweck to mount the discourse in Kraft paper of this Habana Libre. In Exit, the tenth and hopefully not the last Decalogue of Nicanor, the director Eduardo del Llano does a much better job of dissecting the entrails of that Habanita chic posing for an international flasher (despite the contrasting black and white, that now and again ricochets the shocks of light).

“They are talented protagonists of an imminent Cuba,” the author declared to Diario de Cuba during the opening. Although to me it shines with a retro aesthetic, fifties-like, with the convertibles and wine glasses and brand name rags of a certain provincial star-system that would have delighted G. Cain*** (if the magazine Carteles has not succumbed to the barracks in the key of cool-war communism).

Beyond a certain progeny of patriarchs (Castro/Guevara & Sons, Ltd?), in most cases they are citizens irregardless of the accumulation of capital (“internationals, although travel is difficult”; “fashionable, although Cuban couture is an oxymoron”; “a prosperous class enveloped in an egalitarian society”). For the rest, the general managers are missing here, the czars of Swiss bank accounts, the political diplo-police experts in petrodollars, and a coin collector, etc. It so happens, also missing are the heads paid in hard currency of a mercenary millionaire dissidence, or so the official discourse would have it.

That would have made of Michael Dweck: Habana Libre a Havana plaza of freedom. Not a catalog of pets, not an album to name the species in the zoo, not a sterile room of dissections. “Cubans preserve much more than the metal of old cars: they preserve a now lost way of life,” the catalog tells us. “The country that Kennedy once called that unhappy island’ overflows with visceral enjoyment and beauty.”

Nelson Ramirez de Arellano, director of the Photo Library of Cuba, offered some keys in his cheerful words of introduction. He emphasized the notion of “class” as a materialistic mantra for the future, “without this implying the enjoyment of any privilege other than being connected to the appropriate circle of friends.” (“Despite the negative photographs that the news agencies stamp on the global collective memory, many here lead the good life,” Dweck himself said.)

For “the restless souls of artists and creators,” the nocturnal country “apparently frivolous in this party world” evokes that evoked in verse by Jose Marti and connects with “the warmth and simplicity that characterizes the subjects photographed.” And the fault of the institution unable to gain access to the cash donations of Michael Dweck lies in “the well-known economic blockade” of the guest author’s country of origin, which in its turn only tries “to relate another part of the history that is not told in the USA.”

Sooner or later in some Vogue interview, the art critics will come out with the little cliché phrase of the title of the review. Before the evidence as yet unverified silence is imposed (the banners taken down in the salon speak for themselves). If Havana Libre is a love story, then guilelessness as a conceptual deficiency is more than understandable.

Translator’s notes:

*PMM – Por un Mundo Mejor / For a better world. A Cuban slogan.

**PM – A 1961 short film directed by Guillermo Cabrera Infante’s brother, Saba, banned for its cinéma vérité-style depiction of Havana nightlife, thus inaugurating a period of intense official involvement in the ideological content of artistic endeavors in Cuba.

***G. Cain was a pseudonym used by the Cuban writer Guillermo Cabrera Infante when he wrote film reviews in the 1950s.

February 28 2012