![]() 14ymedio, Rosa Pascual, Madrid, 10 March 2016 — Moscow 1989. Mario, a Cuban journalist working in the press department of the secretariat of the Organization for International Economic Cooperation (OCEI) representing the island in the Soviet capital, attends, with his family, the premiere of the play The Master and Margarita, whose main female part is being played by Dolores, his lover. He has spent months rehearsing the part with her, playing at confusing reality and fiction in its portrayal of the main roles of the novel. Bulgakov’s Russian literature satire, censored in the USSR since 1973, borrows shamelessly from Goethe’s Faust to talk about good and evil and the decadence of Russian Society. In the same way, Arbat Alleys, a novel by the Cuban-Swede Antonio Alvarez Gil featuring the character of Mario, exploits The Master and Margarita to recall the strategies of the dictators over artists and their works.

14ymedio, Rosa Pascual, Madrid, 10 March 2016 — Moscow 1989. Mario, a Cuban journalist working in the press department of the secretariat of the Organization for International Economic Cooperation (OCEI) representing the island in the Soviet capital, attends, with his family, the premiere of the play The Master and Margarita, whose main female part is being played by Dolores, his lover. He has spent months rehearsing the part with her, playing at confusing reality and fiction in its portrayal of the main roles of the novel. Bulgakov’s Russian literature satire, censored in the USSR since 1973, borrows shamelessly from Goethe’s Faust to talk about good and evil and the decadence of Russian Society. In the same way, Arbat Alleys, a novel by the Cuban-Swede Antonio Alvarez Gil featuring the character of Mario, exploits The Master and Margarita to recall the strategies of the dictators over artists and their works.

Arbat Alleys (Verbum, 2016) works like Russian matryoshka dolls. Hidden stories of totalitarianism, of lack of freedom and censorship, of love, of literature and exile, one within the other. Mario’s story contains that of Santiago, Dolores’s father, a child of the Spanish civil war who left his country fleeing fascism to live in another; and Santiago’s in turn, contains that of the Stalinist purges of the artists of Russia’s Silver Age.

Mario is a moderately correct son of the Cuban Revolution in 1989, the year in which Arbat Alleys is set. He studied at Moscow University, he married a Russian, he already has two sons in Cuba and works as a journalist again in Moscow on the day he had to cover a press conference where Nazarov announces a renovation of the organism by the “transformation processes that are being tested in member countries” of the Eastern bloc.

One night in the OCEI building he meets Dolores, with whom he initiates a friendship that leads to passion. It is the young woman who introduces Santiago to Mario, weaving the small and large story of Arbat Alleys, although at times we don’t know which is the greater and which is the lesser.

Santiago Gomez had fled Spain as a child, leaving the side of the vanquished and heading to Moscow, where he grows up and comes into contact with Ariadna – daughter of the retaliated-against Russian poet Marina Tsvetaeva – who appears in the novel as a ghost. Through his literary collaboration – the Spaniard translates Russian literature – is born a deep friendship that lets the young exile know first hand the pain of the vanquished, the repression, and the censorship suffered by artists such as Anna Akhmatova, Boris Pasternak, Isaac Babel, Osip Mandelstam and Vladimir Nabokov. Someday Santiago’s annotations should serve to construct a novel about the drama of silenced Russian authors, so that Stalin’s crimes are not forgotten and the injury to the Soviet Union’s national literature is remembered.

Santiago entrusts his notes to Mario who, from them, writes the novel of the purges of Russian literature. Fascinated by the harshness of history, with his own works censored by Stalin and by Dolores, the journalist embarks on the narration of a story that ends up consuming him.

Mario is not an enthusiastic revolutionary. He is suspicious of the behavior of senior officials, is aware of the shortages that consume the island, and knows that his criticisms of the Cuban government cannot be made in front of anyone. But the regime’s hypervigilance weighs on him, as it does on all Cubans. However, his criticism is lukewarm because he still believes in the many benefits of the Revolution.

But throughout the year – and the novel – the fall of the Soviet bloc passes before his eyes and with it, the principals in which he has been educated crumble. In the historical background of Arbat Alleys is perestroika, the Prague Spring, Solidarity’s victory in Poland, the execution of Ceausescu and the Tiananmen massacre. But the news of drug trafficking in Cuba and, especially, the execution of General Ochoa, cause the final blindfold to fall from his eyes and he begins asking questions.

“Examples like the one I just cited in the cases of Pasternak and Mandelstam are an example of how the arrogant dictator is allowed to humiliate the rebel writer. The laudatory poems, letters of contrition and public acknowledgments of guilt are only the most visible edges of lives and talents that are consumed and disappear in the trough of totalitarian power. Disgracefully, the cultural life of our country has not been exempt from issues of this kind. Although I do not believe it is necessary, I could cite here several cases of humiliating and despotic treatment toward Cuban writers.”

Mario writes this paragraph thinking of Lezama Lima, Reinaldo Arenas and Virgilio Pinera, without being fully aware that as soon as the manuscript falls into the hands of the machinery of power he is immediately classified as a counterrevolutionary.

His friendship with Santiago – whose past as a child of war isn’t enough to relieve him from being suspected by State Security for having visited Spain during the dictatorship – his affair with Dolores, the friendships of his children and even the discussion at customs at Jose Marti Airport in Havana appear in Mario’s seemingly spotless file, making him into a subversive element.

“I am a Cuban who is dying defending that same Revolution that you’re questioning in this book,” charges the State Security official from the Cuban delegation in Moscow. And Mario understands finally that not even his first idea of suppressing the “most problematic” paragraphs will save him. That the only lifeline has been the loyalty of an official who decides to put friendship ahead of the Revolution and the Party. That the only redemption possible is in his family and in the preservation of the original manuscript, which should be published somewhere in the world to denounce the terror to which dictators subject their artists, surely out of fear of the force and power of intellectual creation and its capacity to make others think.

Alvarez Gil has squeezed the maximum from The Master and Margarita as an explicit reference throughout the novel to make his own denunciation almost 75 years since Bulgakov began his master work and his fight for freedom of expression. In 1930 the Russian writer sent a letter to the government of the USSR where he said, “The fight against censorship, of any kind and under any government, is my duty as a writer, much as it is an appeal for freedom of the press. I believe firmly in freedom and even would say that if a writer only suggested that freedom is not necessary, it would be the same as if a fish declared that it did not need water.”

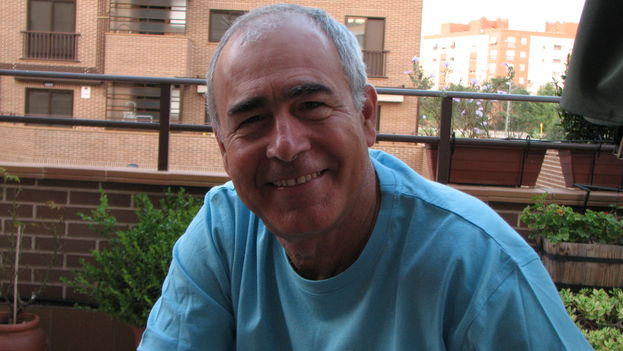

But Arbat Alleys also contains a lot of the life experience of its author. Antonio Alvarez Gil (born Melena del Sur, Havana, 1947) worked in the secretariat of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON) in Moscow for several years, where he experienced the era of perestroika, he married a Russian, translated the country’s writers – Pushkin among others – and ended up in exile, in 1994 in Sweden, although he has recently lived in Spain. His life and career path have served, without a doubt, for the construction of the character of Mario and to make this novel indispensible for recalling the collapse of the Socialist Bloc and the horror stories of those who cemented its construction. An adroit story that leaves a strangely bitter taste, because Mario flees knowing himself persecuted by a regime 30 years later still controls its citizens and intellectuals, but he does it thinking of a future filled with hope.

- Arbat Alleys was first published in Puerto Rico by Terranova Publishing (2012). It has just been reissued in Spain by the publisher Verbum.

- Antonio Alvarez Gil published in Cuba before going into exile. In 1986 he won the Cuban Writers and Artists Union David Award for A Girl on the Platform. With The Long Hours of the Night he was a finalist for the Casa de las Américas Prize in 1993. Outside Cuba he won the International Award for Short Narrative Generation of ’27 in 2005 or XIV Vargas Llosa Prize for Literature in 2005, among others.