![]() 14ymedio, Maite Rico, Madrid, 13 January 2018 — Madrid’s Zarzuela racecourse, with its spectacular grandstands and challenging cantilevered decks, is notable in the annals of architecture. As is Havana’s Focsa building, that “open book” of 39 floors, inspired by Le Corbusier, that dialogues with the bay and Malecon in Cuba’s capital city.

14ymedio, Maite Rico, Madrid, 13 January 2018 — Madrid’s Zarzuela racecourse, with its spectacular grandstands and challenging cantilevered decks, is notable in the annals of architecture. As is Havana’s Focsa building, that “open book” of 39 floors, inspired by Le Corbusier, that dialogues with the bay and Malecon in Cuba’s capital city.

Behind these two emblematic works, so studied, so dissected, lies, curiously, a ghost. A name that does not appear in books or specialized publications. It is not a mistake. It is the oblivion to which two dictatorships, that of Francisco Franco and that of Fidel Castro, condemned a liberal and upright man: the Basque architect Martín Domínguez Esteban (1897-1970).

For decades, the racecourse, conceived in 1934 and opened in 1941, was officially attributed to the engineer Eduardo Torroja. The other co-designers, Martín Domínguez and Carlos Arniches, were erased from memory. The Focsa building is attributed to the architect Ernesto Gómez Sampera. Martín Domínguez is ignored in the guides of Cuban architecture, even in the one jointly published in 1998 by the Junta de Andalucía and the authorities of Havana.

Domínguez swelled the list of architects condemned to exile or ostracism after the Spanish Civil War, many of them purged, such as Josep Lluís Sert, Manuel Sanchez Arcas, Felix Candela, Carlos Arniches and Arturo Sáenz de la Calzada, in what entailed the dismantling of the vigorous Spanish architecture of the first half of the 20th century.

In the case of Martín Domínguez, the exile was double: first to Cuba, when he was 40, and then to the United States, when he was already 62. But his personal defeats in the face of totalitarianism never separated him from his commitment: to put architecture at the service of society. He died in New York in 1970. Today, the tenacity of his son, Martín Domínguez Ruz, also an architect, working with Pablo Rabasco, a full professor of Art History at the University of Córdoba, has allowed the reclaiming of a memorable legacy and biography.

Madrid: Frustrated Dreams

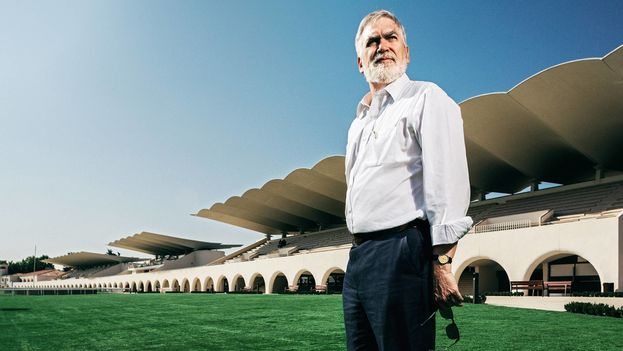

“Look at the arcs, they mark the rhythm of the whole building, the rhythm of a horse’s gallop.” A rhythm paced by the undulating roofs of the spectator stands. A few yards away, the pureblood’s hooves thunder along the track. Martín Domínguez Ruz is 72. At 23 he set foot on the Zarzuela Racetrack in Madrid’s Monte de El Pardo for the first time. It was 1968 and he and took some pictures that, once back in New York, he showed to his father, Martín Domínguez Esteban. The Basque architect, one of the three authors of that project, who had never been able to see the finished work, which had been in progress for two years when the Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936. “My father went into exile and Carlos Arniches, who stayed behind, was censured and could not finish it.” Engineer Eduardo Torroja was able to continue and remained faithful to the plans.”

Like a good architect, Martín the son likes to talk about the philosophy that underlies the structure. The racecourse is a technical feat, yes, but also a way to understand a historical moment.

“My father and Arniches wanted to recreate the sense of a town celebrating fiestas, where the elite mix with the ordinary people, the traditional with the modern, a network of spaces that invites one to walk and come upon the jockeys and the horses, with the paddock in the center, surrounded by arcades, like in the bullfights in the central square of Sepulveda in the patron saint festivities.”

All this combined with a great technical challenge: the large reinforced concrete canopies that seem to wave on the grandstands and that are anchored with their own weight to the entrance hall.

The whitewashed walls and Arab tile roofs unleashed the orthodox criticism of the avant-garde. But Arniches and Domínguez did not want to break with the past. It was about heading into the future based on their own traditions, very much in the humanistic spirit of the Free Institution of Education and the Student Residence, where Domínguez stayed between 1918 and 1925.

His son draws a parallel with the La Barraca theatrical project of La Barraca by Federico García Lorca, a friend of his father. “They wanted to transform an agrarian and cacique society into a more just, more modern and more enlightened one through the architectural language.”

And now it is time to put things in their place. “The racetrack is a unitary work, the result of a dialogue between two architects and an engineer, who unite two contrasting constructive traditions.

There have been historians who have had the temerity to say that the stands were the work of Eduardo Torroja, and that was convenient because Arniches and Dominguez did not have the sympathies of the regime. The reality is that it was a joint work of three professionals who were respected, and memory speaks very clearly. Without Torroja it would not have been like that, but nor would it have been like that without the architects.”

Until 1936, the career of Martín Domínguez Esteban seemed unstoppable. Coming from a family of San Sebastian’s high bourgeoisie, he shared his studio, located in the Palace Hotel, with Carlos Arniches, whom he met in 1924.

Both participated fully in the modernizing movement that was making its way into Spain. They were involved in the construction of the Road Hostels of the National Tourism Board (the seeds of the Paradores Nationales – a series of luxury hotels created in historic structures), an initiative of 1928 to promote car tourism and to update the appalling hospitality infrastructure in the interior of the country.

They worked with agricultural villages and collaborated with their mentor, Secundino Zuazo, in the construction of the Nuevos Ministerios (government headquarters). And they turned their attentions to the project of educational renovation with the School Institute and the Kindergarten (today, the Ramiro de Maeztu Institute) and the Student Residence Auditorium on Serrano Street (destroyed at the end of the war and reconstructed, using part of the original, by Miguel Fisac as the Chapel of the Holy Spirit).

When war broke out, Domínguez offered himself to the Captaincy General to work with other architects on the plans for the defenses of Madrid,

which were to be built by unemployed workers. The labor unions rejected the plan. “My father saw that the war was lost, and he told Juan Negrín that,” recalls his son.

In December of 1936, Domínguez crossed the French border on foot. Lluís Companys had interceded with the leader of the CNT (National Confederation of Labor) to give him a safe conduct (“he has a friendly face, we let him out,” the union leader told him). He ended up in Antwerp and embarked on a ship bound for Veracruz. From there he planned to travel to the United States. The ship made a two-week stopover in Havana. And the architect changed his plans and decided to stay on the island. Carlos Arniches, on the other hand, is cloistered in an internal exile until his death, in Madrid in 1958. In those years he built the settlement colonies of Algallarín (Córdoba) and Gévora (Badajoz) and the Center for Tobacco Studies, in Seville.

Havana: The Golden Years

April 2017, Martín Domínguez Ruz speaks at the School of Architecture of Cuba about the process of creating the Hipódromo de la Zarzuela with the same slides that his father had used. He has not been in his native country, which he left as a teenager, for 58 years. The meeting provokes mixed sensations.

“I’ve never seen so many police and military officers in one place, but then you say … God, what a beautiful city, and the contact with unofficial people is so kind and so warm, I found very few people attached to the regime.”

He decided to return with Pablo Rabasco to look for the traces of his father, especially in the public housing he developed in several neighborhoods in Havana. But none of the experts will help them. “Their careers were in danger, it turns out that the one who developed those plans was not Che Guevara’s New Man, but a liberal and democratic man, who left Cuba and was later called a gusano, a worm. So now the designers have become the revolutionary architects of the National Housing Institute. Changing the story is going to be difficult.”

The Cuba that Martín Domínguez Ruz’s father knew was very different. An effervescent country, with a buoyant economy and a hectic cultural life. But there was a problem: the College of Architects refused to recognize his professional title.

“It was because of ‘corporatism’. On my birth certificate, dated 1945, I am the son of Josefina Ruz, secretary and domestic worker, and of Martín Domínguez Esteban, interior decorator. In spite of everything, Domínguez Esteban soon begins to stand out. He associates with other architects, signing plans as the treasurer or engineer.

With Miguel Gastón he builds the Radiocentro building in Havana’s Vedado neighborhood for the CMQ Communications Group, the most important in Cuba. Completed in 1947, it was the first multifunctional complex in the country, with shops, offices, radio and television studios and the Warner cinema (today, renamed the Yara Cinema). Walter Gropius, the founder of the Bauhaus School, praised him on a visit to Havana.

Specifically to provide accommodation for the station’s employees, Martín Domínguez’s most audacious project in Cuba arose: the FOCSA building (Fomento de Obras y Construcciones, SA), undertaken with Ernesto Gómez Sampera. The building, which at 39 floors was at the time the second highest concrete structure in the world, was raised as a small self-sufficient city, following the parameters of Le Corbusier, one of Martín Domínguez’s great inspirations, whom he had met while working on the Student Residence in Spain.

The building was structured in two wings that take off from a central hinge and the number of stories was a technical feat. The FOCSA should have received the 1957 Gold Medal from the College of Architects, but the 26th of July Movement’s assault on the presidential palace that year caused the cancellation of the awards.

By then Martín Domínguez had been involved in the construction of social housing for unions, on land bought by the FOCSA company. After the triumph of the Revolution, the architect recommended that the owners to sell the land to the state, before it was confiscated.

“My father saw everything coming from the beginning, because of his experience on the Republican side [in Spain], he soon identified Fidel Castro’s speeches with those of La Pasionaria (Dolores Ibárruri), ‘I’ve heard it before,’ he said. He knew very well where this was going. My mother did not, but he did.”

The FOCSA group sent him to talk with Che Guevara who headed the Ministry of Housing and La Cabaña Fortress. “Every morning they were shooting people there, the blasts could be heard all over Havana. He negotiated with him to sell the land, below the purchase price, of course. Then Che invited him to dinner.”

And there Martín Domínguez sealed his fate. Commander Guevara wants to know more about him. “Well, Domínguez, you are a Spanish Republican, and what are your ideas?”

“My ideas?”

“Yes, your ideas.”

“From the personal point of view I am conservative, and from the political point of view I am a liberal.”

After that conversation, agitators began to arrive at jis projects, to incite the workers to revolt. Meanwhile Dominguez, together with Gómez Sampera and Ysrael Seinuk, had presented the project for the Libertad Building, a spectacular 50-story skyscraper, to an official contest to commemorate the Revolution. “The jury of architects was going to give them the first prize. My father did not appear, of course, but when they told Fidel about the project he said he did not accept it, saying ‘this gallego is not going to build in Cuba’.”

Ithaca: End of the Journey

Martín Domínguez Esteban knew that the time has come to return to exile. He accepted a job offer from the prestigious Cooper Union University, in New York, and waited for months for a criminal background check certificate from Spain that never came.

At the end of April 1960, the architect leaves Havana on a boat bound for Miami, with his wife and son, aged 15, with a car, some clothes, photos, $150 per person and one book each chosen from the family library. The father chooses Manuel Azaña’s essays. The mother, a Spanish rice cookbook. The teenager, the complete works of García Lorca.

“We spent a night in Miami, I wanted to stay longer, we had family, but my father told me: ‘We are not staying a moment longer than necessary, your mother and I will never go back to Cuba. I do not want to live with yearnings and false expectations. We are not going to look back. Always ahead’.”

When they arrived in New York, someone else had been given the job at Cooper Union because of the time that had passed, but he got another teaching position in upstate New York at Cornell University, in the city of Ithaca, which he defined as “a Siberia with modernist airs.”

At this time, Martín Domínguez Esteban was 62. He reinvents himself again, he is happy to teach, he works as a consultant on housing programs in Latin America and designs the beautiful Lennox House, his final work. “My father faced the second exile with his sense of humor and integrity intact. He had an unusual strength of character. In Ithaca, despite the low temperatures, he continued to take his cold shower every morning.” But behind his humor and elegance, he always lived in that “constant hunger of exile” mentioned in the Greek tragedies, a hunger that, in the end, could never be satisfied.

An annual award with his name celebrates Martin Dominguez Esteban at Cornell University, which dedicated a great exhibition to him at the time. The award in Madrid is the second. “Our goal now is to have one in Havana,” says professor Pablo Rabasco enthusiastically. “It will be the best way to close the circle.” And erase oblivion.

Editor’s Note: This text was initially published in the Spanish newspaper El País.

__________________

The 14ymedio team is committed to serious journalism that reflects the reality of deep Cuba. Thank you for joining us on this long road. We invite you to continue supporting us, but this time by becoming a member of 14ymedio. Together we can continue to transform journalism in Cuba.