![]() 14ymedio, Miriam Celaya, Havana, 26 March 2018 – It is quite possible that when Yimit Ramírez – until recently a young and unknown Cuban filmmaker – decided to make his first feature film, he did not aspire to become a sort of sacrilegious monster himself. Even less would he think he was turning his team into a bunch of apostates.

14ymedio, Miriam Celaya, Havana, 26 March 2018 – It is quite possible that when Yimit Ramírez – until recently a young and unknown Cuban filmmaker – decided to make his first feature film, he did not aspire to become a sort of sacrilegious monster himself. Even less would he think he was turning his team into a bunch of apostates.

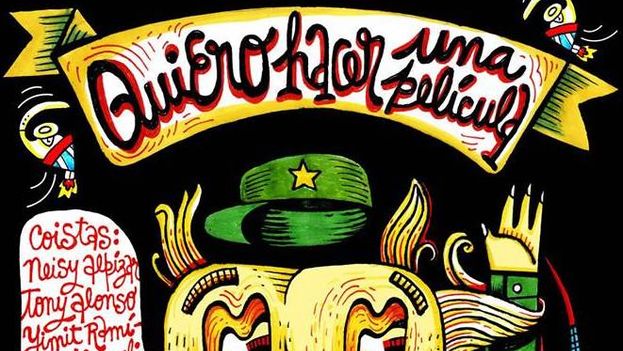

I Want to Make a Movie (Quiero Hacer Una Película) is the title of a motion picture whose projection was planned as a work in production with an included debate, at the theater on 23rd Street and 12th in the center of Havana’s Vedado neighborhood, within the Special Presentation section of the XVII Muestra Joven Show, held between April 3rd and 8th. At the last moment, the work did not pass the test of the low barrier of the official censorship of the Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry (ICAIC) due to a detail found unacceptable by the Torquemada1 of such a virtuous institution. During a brief segment of the film, a young adolescent character refers to the most famous hero of the Cuban independence, José Martí, by the offensive terms of “mojón” (turd) and “maricón” (faggot).

As a result of such mockery, the film was relegated to a quasi-symbolic exhibition in the small Terence Piard screening room, with capacity for a small audience of only 24 spectators, the reason for the filmmakers’ decision to retire the movie from being shown.

The ICAIC not only suspended the press conference where the filmmakers would give their own views on the matter, but also divulged their own statement explaining their intolerance to what they consider “an insult to Martí.”

The reaction was immediate. The ICAIC not only suspended the press conference where the filmmakers would give their own views on the matter, but also divulged their own statement explaining their intolerance to what they consider “an insult to Martí.” The film producer and the coordinators of the event used the social networks – obviously, they knew that they would not be granted space in the official media – to express their disagreement with the ICAIC’s decision and to promote a public debate.

As a greater irreverence, the filmmakers exhibited a fragment of the movie where the above offensive epithets against Marti that led to censorship takes place, making public precisely aware of what the official “watchmen of virtue” sought to silence.

Everything indicated that, for the purposes of national public opinion, the matter would remain on social networks, that is, circumscribed to the small segment of Cubans who have access to the Internet, and within the usual gossip of those “in the know”. However, the censorship and scolding seemed insufficient punishment to the art curators, so that the powerful monopoly of the official press has also lashed out – with even a stronger force, the Apostle (as Cubans call José Martí) would have said – against the filmmakers.

The most recent (journalistic?) pearl about the subject has been an extensive article by Luis Toledo Sande, taken from Cubarte and reproduced over six columns in the Sunday edition of the Juventud Rebelde newspaper entitled Fatal Bullets against José Martí (With the Objective of a Movie in Production).

The article is a difficult read, and too bombastic to be credible, where the abundance of accusations against the young filmmakers contrasts with the lack of clarity in language and arguments.

Judging by the angry speech of Toledo Sande, it could be said that Cubans are a people given to the veneration or idolatry of the founding fathers of the nation

Judging by the angry speech of Toledo Sande, we would say that Cubans are a people given to the veneration or idolatry of the founding fathers of the nation, when in fact the excessive tendency to derision that characterizes the natives of this island results in nothing – or almost nothing – seeming sufficiently sacred to them.

In any case, the closest examples of veneration evidenced in Cuba are the procession of Our Lady of Charity – Cachita, as she is more popularly known – who corresponds to the deity Oshún (or Osún) in the popular tradition of the Yoruba religion heritage, and the numerous yearly pilgrimages to Rincón, to fulfill promises or to ask for healing miracles to San Lázaro, or Babalú Ayé, also in the Yoruba religion. In both rituals there is a strong base of superstition and practicality, rather than a feeling of true holiness.

But in the heat of his revolutionary delirium, Toledo Sarde considers that the movie makers have not only mocked the “massive veneration” of Martí, who has been granted “the brand of the sacred” in Cuba, but they have crossed the limits of freedom of creation to become practically traitors to the nation, just like the shadowy “enemies of the Revolution”, who invoke the name of Martí to destroy Cuba.

“The dialogue in particular (disclosed by the producer of the film on social networks) contains rudeness that had not reached any of the most bitter Martí detractors,” exclaims Toledo Sande, indignant. Which justifies censorship because “the nation would be in very bad straits if, blackmailed by the maneuvers of its enemies (…), would even tie its hands so as not to stop what must be stopped”.

And, since “at this point it’s senseless to speak of the ‘trusting ones’,” Toledo Sande says that the affront to the Apostle in the case of the aforementioned film constitutes no less than a “poison”.

Now, beyond so much hypocritical patriot scorn, this attack on an unfinished movie, unseen by the public and against a small team of unknown filmmakers, is extremely disproportionate. The point is not that reviling Martí or your neighbor is right or wrong, but seeing the facts in their proper dimension, without tears or tango passions.

Beyond so much hypocritical patriot scorn, this attack on an unfinished movie is extremely disproportionate.

Sticking to the mere object of the scandal – just a few “bad words” in the dialogue of a feature film – what could be the insult? Is it that the official homophobia in this misogynistic and patriarchal society cannot tolerate that the National Hero be branded as queer? The defenders of revolutionary virtue should clarify the point: if Marti’s transcendence is derived fundamentally from his actions for Cuba’s independence, why would attributing a certain sexual orientation to him be so offensive? Would Mariana Grajales2 lose her title as “mother of our country” if some archival document is found indicating she was a lesbian? Would someone who referred to her as “Mariana the Butch” be labeled a traitor?

There are written testimonies of participants in the emancipatory deed that assure that both Máximo Gómez -the flamboyant Generalissimo of our two Wars of Independence- and the ultra-brave Antonio Maceo – labeled with the nickname “Bronze Titan” – an epithet that today would accuse a certain suspicious whiff of racism – felt an undisguised disdain for José Martí, whom they called contemptuously “the Delegate”. Yet, both Gómez and Maceo have a high focal point in the pantheon of patriotic glories.

However, the really rude thing is that the Cuban government, specifically the late Fidel Castro, has insulted so many times and with impunity the memory of the Apostle Martí by pinning the José Martí National Order, conceived in 1972 to distinguish “Cuban and foreign citizens and Chiefs of State or Government for their great deeds in favor of peace, friendship and humanity’s progress”, on the chests of representatives of repressive regimes – such as Soviet Leonid I. Brezhnev, Ethiopian Mengistu Haile Mariam, Romanian Nicolae Ceausescu or Czechoslovakian Gustav Husak, for example – and even on the chest of worldwide repudiated genocidal individuals – like Zimbabwean Robert Mugabe and Cambodian Heng Samrin – without anyone in this Island, pregnant with virtuous admirers of Martí, having raised their voices in protest against such scandalous affront.

What really hides under all the commotion around a simple fiction movie is the unspeakable fear of the leadership and its servants before an uncertain national and regional horizon

What really hides under all the commotion around a simple fiction movie is the unspeakable fear of the ruling dome and its servants before an uncertain national and regional horizon.

And all this without forgetting what an insult it is to bestow Martí with the intellectual authorship of a violent, armed assault, in broad daybreak, against military barracks where soldiers of the constitutional army were sleeping – and not criminals – an attack that today would classify as a terrorist act and one that, at the time, only served to satisfy the dreams of glory and greatness of a megalomaniac, who ended up becoming the leader of the longest and most destructive dictatorship that this island has ever known.

But more than the ridiculous divinization of the Apostle or the alleged defense of our national values by the commissaries of the Castro regime, what really hides under all the commotion around a simple fiction movie is the unspeakable fear of the leadership and its servants before an uncertain national and regional horizon, in the midst of which the transfer of the government of the ex-guerrilla elders to a new generation of supposedly “faithful ones” must take place.

The point is not that a presumed veneration of the Apostle is crumbling, but that every little civic irreverence seems to remind the autocrats that, for them, there will not even be pedestals.

1 Tomás de Torquemada (1420-1498) Spanish Dominican monk, first Grand Inquisitor of the Spanish Inquisition

2 Mariana Grajales and her family served in the Ten Year’s War, the Little War (1868-1878) and the War of 1895. She was the mother of José and Antonio Maceo Grajales, who served as generals in the Liberation Army from 1868 through 1878. During her time serving in the war, Mariana ran hospitals and provision grounds on the base camps of her son Antonio, frequently entering the battlefield to aid both Spanish and Cuban wounded soldiers.

Translated by Norma Whiting

________________

The 14ymedio team is committed to serious journalism that reflects the reality of deep Cuba. Thank you for joining us on this long road. We invite you to continue supporting us, but this time by becoming a member of 14ymedio. Together we can continue to transform journalism in Cuba.