![]() 14ymedio, Havana, 7 January 2019 — The battle to win the constitutional referendum of February 24 has led the Cuban Government to take all types of actions. Along with advertisements for “I’m voting Yes” at baseball games and the avalanche of messages of support on social media, it has opted for censorship of text messages that include calls to vote No or to abstain.

14ymedio, Havana, 7 January 2019 — The battle to win the constitutional referendum of February 24 has led the Cuban Government to take all types of actions. Along with advertisements for “I’m voting Yes” at baseball games and the avalanche of messages of support on social media, it has opted for censorship of text messages that include calls to vote No or to abstain.

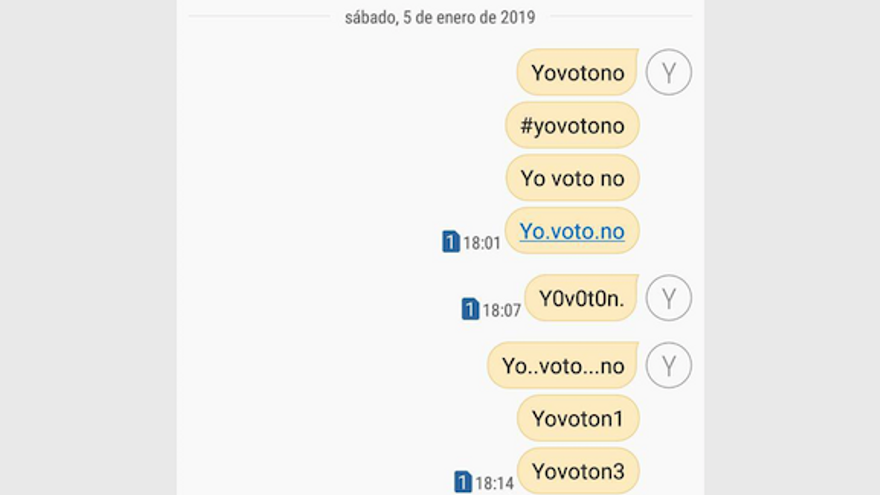

Mobile phone customers who have sent a text message with the phrases “YoVotoNo” (ImVotingNo), “YoNoVoto” (ImNotVoting), or with the word “abstention” (with or without the accent in the Spanish spelling) are indignant because the text never reached its recipient. 14ymedio has confirmed this situation with a test that included more than fifty users in ten provinces.

That test showed that combinations that include the numeral symbol, in the manner of hashtags on social media (#YoVotoNo and #YoNoVoto), are also “clipped” by the Telecommunications Company of Cuba (Etecsa), a state-owned monopoly that in the past has seen itself involved in other cases of censorship and of blocking telephone services against activists.

The contract that every user of Etecsa’s mobile network signs upon purchasing a mobile phone line includes a paragraph in which it makes clear that among the causes for the termination of service is that it be used for a purpose “that threatens morality, public order, the security of the State, or aids in committing criminal activities.”

However, no customer has been warned that messages will be submitted to a content filter or that part of their correspondence will be blocked if they mention the name of opposition figures, spread slogans uncomfortable for the government, or promote an electoral stance different from that of the government.

The current censorship of words and phrases does not extend to messaging services like WhatsApp, Telegram, or Facebook Messenger which the government cannot intercept in as easy a manner as it can control the text messages sent via Etecsa. For that reason many activists promoting “No” in the referendum or a voting boycott have moved toward these tools.

“I realized that something was happening because I went to send my sister who lives in Havana a message with the comment that a friend of mine made on Facebook about the referendum,” a cellphone user who wished to remain anonymous told 14ymedio. The text included the tag #YoNoVoto and never arrived to its destination, although the 0.9 CUC for the delivery was subtracted from the sender’s cellphone credit.

“After that I sent her various combinations of that same phrase and it was only delivered when I changed the ’o’ to a zero and I substituted the final vowel with a period,” says the source. “I spent the early morning hours checking with other friends and the result was the same,” the source concludes.

After that first claim, this newspaper communicated with the service number for Etecsa (118) to investigate what happened. The employee who answered the call insisted that there hadn’t been previous reports of problems with text messaging and emphasized that “Etecsa is not currently doing any maintenance work, so all messages should arrive on time.”

When asked directly about a possible censorship of text message content, the state-employed worker declined to respond and said she knew “nothing about that matter.” Other calls, made at different times this weekend, produced similar results.

It’s not the first time that Etecsa has censored messages based on content. In September this newspaper revealed in a comprehensive report that all text messages that contained references to “human rights,” “hunger strike,” “democracy,” “repression,” or the names of the most well-known activists in the country, were never received even though they were charged for.

At that time, 14ymedio did tests from accounts of very dissimular users, who ranged from opposition figures and activists to people with no links to independent movements. In all cases, messages that contained certain expressions were lost along the way.

Arnulfo Marrero, second in command at the Etecsa plant at 19 and B in Vedado, Havana, appeared at that time surprised by the complaint presented by two reporters from this newspaper. “We don’t have anything to do with that, you should address the Ministry of Communications (Micom),” explained the official.

“Micom is who governs the communications policy, because we here have no say. The only thing I can do is report this,” warned Marrero.

With more than five million cellphone users, Etecsa does not seem prepared to give in on the ideological control of the messages circulating on its network and continues to expand its extensive history of text message censorship via a “list of key words.” Now new terms have been added to that list of phrases and terms that, it seems, will continue to grow in the future.

Translated by: Sheilagh Carey

_______________________

The 14ymedio team is committed to serious journalism that reflects the reality of deep Cuba. Thank you for joining us on this long road. We invite you to continue supporting us, but this time by becoming a member of 14ymedio. Together we can continue to transform journalism in Cuba.