Here in Cuba we have the habit of calling small state businesses puestos — places — those businesses that, up until recently, sold agricultural products through the poorly-named “supplies book” (seldom did it supply us), for prices subsidized by the state.

Their prices were similar to those set for currently for the diminished medical diets, which minimized the impact of the high prices of “liberalized” products (products not subsidized by the State). These shops exist today exclusively to dispatch produce that has been advised by the such medical diets—prescribed by a physician for specific aliments—and, every now and then, a few other agricultural products.

In the absence of any armed conflict in the past fifty years—but also in spite of the continued and systemic crisis in which the nation has been immersed—nobody understands why the said “supplies book” is still in place; though given the lack of supplies and the helplessness into which the Cuban people are sunk, most people vote for its continuation, based on the logic that it’s better to have something, even if it’s little and bad.

Nowadays, some products have been liberalized — that is taken off the rationing system — and there are fewer and fewer priced under government subsidies. Salaries continue to be symbolic in today’s Cuba, so the prices of products in stores selling in “hard currency” or that sell “released” products (that is those no longer rationed) are prohibitively unaffordable for the majority of the population.

Such establishments often find themselves in the nude when it comes to merchandise, and even when they do have merchandise, the seller has managed to build on a clientele that has more economic solvency, and to whom the products are sold in bulk, for a better price, and more quickly, leaving them with more time for other activities; we all know that when these businesses lack merchandise, they simply close down until the next delivery is made.

The one at the corner where I live (Freyre de Andrade and Juan Delgado, at La Víbora) is yet another example of the deterioration Cuba has undergone since 1959. The corner that like a coquettish, tidy, well-made-up and proud girl (like a permanent Sunday), used to distinguish its surroundings, is today—like almost anything around us which is not a propagandist display window that the State presents to the world—a depressing and ruinous eruptive engraving that has soiled our urban landscape, and become a synonym of abandon and lack of hygiene. The worst of it all is that we have become accustomed to it.

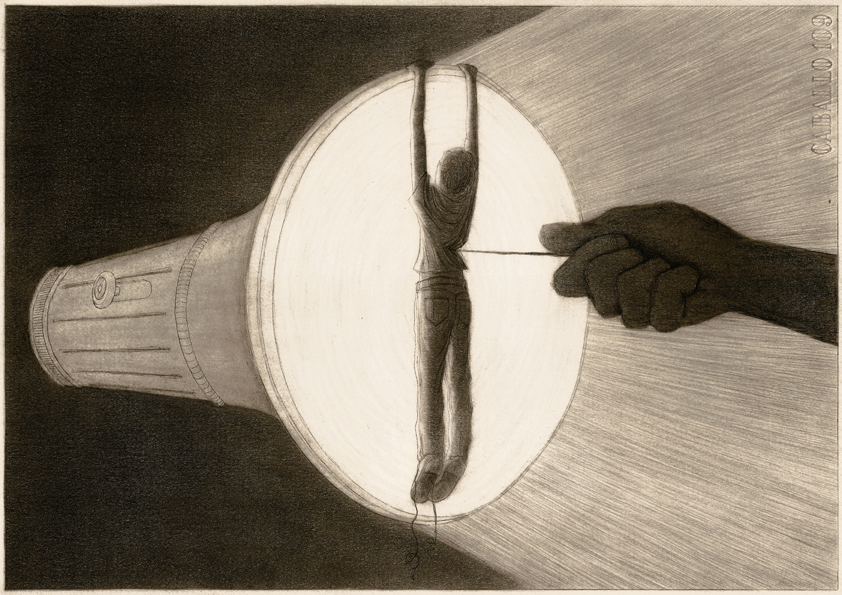

In regard to such establishment, which—as shown in the image—is closed to the public during working hours and days, some people from the neighborhood jokingly put forward that it is “un puesto que no tiene nada puesto” (or, less cleverly in English, “a naked place”) which would actually make it a “porno store…” Nothing like popular irony. But if it weren’t for such an attitude in the middle of adversity…

Translated by T

January 31 2011

Rafael Felipe Martínez Irizar, a Cuban citizen of mixed race from Cienfuegos, and the son of Alfredo and Gregoria, will turn 44 this coming May 26. A few days later, he will have served 2 of the 5 years imposed on him as a sanction for the crime of illegally leaving Cuban territory.

Rafael Felipe Martínez Irizar, a Cuban citizen of mixed race from Cienfuegos, and the son of Alfredo and Gregoria, will turn 44 this coming May 26. A few days later, he will have served 2 of the 5 years imposed on him as a sanction for the crime of illegally leaving Cuban territory.