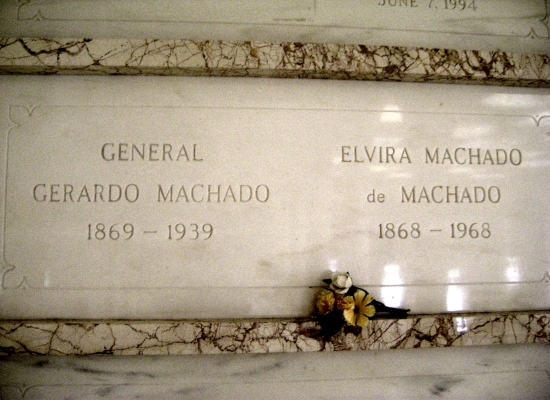

MIAMI, Florida. — In the North Cemetery of Woodlawn Park, in Miami, lie the remains of the former Cuban president Gerardo Machado y Morales (1871-1939), who was the politician who constructed the most works during the Republic, and also was the first who opposed the international influence of communism.

To Machado, the new writing of history is simplified by a caricature: the ass with claws, and as all that is not convenient to them, they leave his image, alone and deformed, surrounded by a sea of silence, in which the only thing heard is the murmurings of the communists.

Was he a dictator? Yes. One that induced a reform in the Constitution in 1901, to govern for ten years? Yes, but he was highly adored, in an epoch quite convulsive. Did he close the University of La Habana (Havana), in 1930? Yes, but he had constructed its staircase, and the then new buildings of the Colina — including the School of Engineers and Architects,which today is in ruins.

Did he suspend constitutional guarantees? Yes, but terrorism had seized control of the streets, and there did not exist negotiations with opposing groups. Did he engage in political assassinations and torture? Yes, but not so much as since 1959. continue reading

According to Ramiro Guerra, some 5,000 revolutionaries were imprisoned provisionally, and Juan Clark affirmed in his book Mito y realidad (Myth and Reality) (1990) that “the prisoners were usually treated correctly, enjoying prisoners’ privileges and amnesties that returned them to liberty after a short stay in the presidio (prison).”

His legacy of modernity

With all his shortcomings — of repression, and desires to prolong his mandate — his government defended national interests, and constructed in Cuba, as had never been done before. To mention only a few such works, during the eight years of economic growth, he constructed:

— The Carretera Central (Central Highway) (with its 1,144 kilometers, just under 700 miles), that until today has not been exceeded, in such a project of vital integration of the provinces.

— The Capitolio Nacional (National Capitol) (1929) that remains the paradigmatic building of Cuban architecture, and the most luxurious in the country.

— Important plazas (the Park of Fraternity, or Brotherhood), walkways (the Avenue of the Missions, in front of the Presidential Palace), and avenues (Fifth Avenue, (Avenue) de Playa (beach)). Furthermore, the Paseo del Prado was remodelled.

— Important buildings, such as the National Hotel, the Asturian Center (today the National Museum of Fine Arts), the Bacardi, the Lopez Serrano, the hotel Presidente del Vedado [“forbidden,” probably a place name].

— Public works: the already-mentioned University of Havana, the Technical Industrial School, de Boyeros [“oxherd,” probably also a place name], the Pier of Slaughters or Meat Markets, the Palace of Justice of Santa Clara, the Model Prison of the Isle of Pines, among many others.

He increased tax collections, providing that the Law of Public Works would impose a charge of ten per cent on all imported articles considered to be luxuries, and another of three per cent on all products of foreign origin, except food. That caused a lowering of imports, and the development of national industry, creating works of painting, shoes, matches and of products not linked to sugar cane and tobacco.

And in 1927 he approved a new Law of Customs and Duties (Tariffs) to protect and stimulate agricultural and industrial production. It was the first time that Cuba independently had its own customs tariff, of a modern type, one designed to protect its own interests. The production of birds, eggs, meat, butter, cheese, beer and footwear increased markedly. Likewise, Cuba joined several commercial treaties (Spain, Portugal, Japan, Chile) in a completely independent manner.

Machado was a popular president, during his first term. In April of 1927 he travelled to Washington, and sought from President Coolidge a treaty that would eliminate the Platt Amendment. In the act of inauguration of the Sixth International Conference of American States, in January 1928, a proclamation was declared “a vote of gratitude and applause in favor of the excellent Sir General Don Gerardo Machado.”

And on the 1st of November of that year, in the elections celebrated under the electoral Law of Emergency, Machado was presented as the only candidate and was re-elected without opposition of the other parties, for a mandate that would end on May 20th 1935.

The Enemies of Machado

The discontent towards Machado had above all economic roots. The Great Depression — that began with the bank crash of October 1929, and that only began to ease in the middle of the decade of the Thirties–unleashed a great popular animosity against his government and members of his administration.

The almost total paralyzing of commerce, the sudden devaluation of the price of sugar (which had attained its highest price in 1927), the lack of work, and the reduction and the delay of State payments, brought the country to a state of misery overnight, that reached its maximum degree in the summer of 1933.

The second obstacle of his government was international communism. Barely three months after he attained the presidency, the first Communist Party of Cuba was founded in Havana, the 16th of August, 1925. The new ideology, that was guided by the soviet ideal, utilized methods that were unknown until that epoch. The terrorism of bombs in the cities was introduced in Cuba by Catalan emigrants.

The Sixth World Congress of International Communism (between July and September of 1928), which took place in Moscow, approved the slogan of “class against class.” Dozens of foreigners were expelled from the country, for being dedicated to “the propagation of communism.”

Machado tried to stop the discontent; but neither the suspension of constitutional guarantees (in June of 1930), nor the imposition of martial law (with the use of military tribunals instead of civil tribunals), nor press censorship, nor assassination and imprisonment of the opposition were able to halt the campaign of terrorism of the revolutionaries, headed by the ABC, the Revolutionary Union, de Guiteras, the Student Left Wing, and the Student Directorate of the University.

The United States followed with concern the political situation in Cuba, until on the 8 August 1933 the ambassador of that country, Sumner Welles, presented himself at the Presidential Palace with a note from the President of the United States, Franklin Roosevelt, in which Roosevelt demanded Machado’s resignation, and with that the end rapidly approached.

The incipient liberty of the press also conspired against Machado, given that the journalists would not write in favor of a government, unless they were given payment, or they received a “bottle” — that would be worth about 500 pesos. Machado refused to give “bottles” to the press, unlike the previous government, that of Zayas.

But his greatest enemy was the fickleness and immaturity of the Cuban people, which, equal to that in 1959, left them blinded by messianic illusions that promised them heaven on earth. The Revolution of the 30 produced Fulgencio Batista, who would pull multitudes in 1940, with the support of the communists. Then came student leaders like Ramon Grau San Martin and Carlos Prio Socarras, who governed in the name of the revolution.

The magazine Bohemia, in October 1933, published an article by the overthrown president, in which he reflected: “During a time I was the Man God, the New Messiah, the Mentor Man, who could do everything, and afterwords, by the same people who had exalted me, I was Satan, Moloch, Mars uplifted. Thus is all Cuba: the country that appears to be made with the blades of a windmill.”*

The story of the political conflicts cannot be divided into the good and the bad, without defining the relationship of social groups surrounding a power structure. Some kill in the name of the Law, others in the name of the Revolution. But some build, and leave a legacy of modernism, such as Gerardo Machado, while others empty history, and they destroy all in their path, such as Fidel Castro.

Cubanet, June 23, 2014

*Translator’s note:This appears to be a reference to Don Quixote, as if Cuba became what it did by its vain tilting with windmills.

Translated by: Diego A.