The Cuban identity that we cling to, that we are used to identifying with, isn’t, of course, the country that we left behind around the end of the 70s; not even, in other cases, ten or fifteen years before that date; but rather the republic that preceded Castroism and that Castroism froze in the memory and the longings of more than a generation, while forcing an entire society into a totalitarian permanence.

Paradoxically, that freezing that takes place, above all, in our minds, in our consciousness, contrasts with a radical transformation of the essential in Cuba — or that such as what we have — that doesn’t stop in the suppression of fundamental liberties, nor in the destruction of the entire economy, private and public, nor in the aggression against the environment; but rather, anxious to rewrite history and replace the past, in a society orphaned of its natural ruling classes, the State induces, through malice or through lack, the collective debasement of citizens’ customs, commonness as a norm of social commerce, larceny as natural compensation, and prostitution as a redeeming aspiration. Impotent and horrified, many of us have witnessed this shipwreck, whose consequences, like a hangover, also arrive to this shore to alter — if not to contaminate — our understanding of what it is to be Cuban. continue reading

Out of our love and stubbornness, there exists another Cuba from this side of the sea: a community deeply entrenched in the time of nostalgia, incapable of renouncing even the most insignificant of the memories that it hoards and that it considers inseparable from the national identity that we want to see restored to its inherent territory, as if this half century were nothing more than a bad dream.

We want, because I include myself among them, to be returned to the country that we lost — by whom? we don’t well know if Divine Providence or “the Americans” that, at times, can end up being confused — and to be allowed, in an act of love and discipline, to return to the Cubans from there (and some of those who went) the lost manners, the authentic patriotism, the morals that seem to have been drained in some sinkhole, the will to participate actively in the political life of one’s country, the decorum, in short, that is an essential ingredient of robust and prosperous societies.

But what’s certain is that the great majority of Cubans corrupt themselves, according to our criteria and, at the same time, we lack the political instruments that are indispensable for even trying to revert that process of corruption. Cuba has been transformed into something else without our being able to do anything, or nothing that can really have a genuine effect. Additionally, time (that of our freezing and that of the destruction of our country and its nation, one and the same) works against us.

On the eve of ten, of twenty years (that have to pass more rapidly than we would like), those who retain our vision of Cuba will be many fewer than today, while those that have incorporated the features of debasement will have grown by millions. In this race against time, the figures alone go against us. If another generation passes waiting for Cuba to return to the real time of history, there will remain almost nobody to tell about the illusion of our aspiration.

So, has Cuba been lost? Is Castroism — not the communist regime that has by now proven to be a universal fiasco, but rather its social and moral consequences — irreversible? Is it perhaps naive to try — and even to put some effort in it, as we have done, each one with the methods and talents at his disposal — to restore the nation (I mean to say, the body of institutions, traditions, customs, behavior, etc.) that we once had?

Giving space to pessimism, I dare to respond affirmatively to these questions. The totalitarian devastation leaves the Cuban people without foundations or models and, as a consequence, easy prey for domination. Those who don’t compromise, those who remember how things were, emigrate in the vast majority, and that emigration accelerates the poverty and alienation of those who stay.

Theirs is the harsh reality of the institutionalized misery, vassalage, and despicable skepticism that this generates. For us, a series of dreams of what was our country, of what it could have become, of what we still would like it to be. Rarely has the reality of two segments of the same nation been so distinct.

In its origins, Cuba was also a dream, a dream of a group of aristocrats and intellectuals close to them, whose comfort, in the majority of cases, also carried the stigma of slave labor. They had read, they had traveled, they aspired for the plantations they lived on to be a more efficient and educated — in the beginning, not even much more just and independent.

The colonial power closed all avenues to the rich and cultured creole who felt himself a pariah in his own land, and the Cuban nation rose as a distinct entity, separate from Spain, and that separation would end up paying for itself with a lot of blood.

The definition of Cuba is a European chimera, certainly a dream of distinguished white people who popularized that idea, who sell it, who propagate it, who preach it, who end up imposing it. The rest of the population are manual workers, peasants, Spanish shopkeepers — or their children — and slaves.

In the middle of the 19th century, the black population, if we only count the slaves, almost equaled the white and, together with the free black population, was greater than the white. Although the blending wasn’t as obvious as it is currently, it already existed at the borders of these communities. Cuba is rich, it’s true, but its wealth has been made on the sweat and blood and backs of hundreds of thousands of slaves.

Those who dream of Cuba aspire to the perfection of a European republic in the middle of a Caribbean plantation. I don’t blame them, I too have always dreamed of the same. The wars of independence, which served as a crucible for melting many prejudices and accelerating democracy, also served to consecrate the prominent institutions of the patrician ideal of the nation: a straitjacket — to use a metaphor — that they imposed on the black slaves and Spanish shopkeepers; an ideal with which one had to live, with institutions forged for a class that it was a duty to imitate.

Castroism dynamited that social contract, pillaged the wealth that the authority’s code of laws offered, demonized the past, satirized the paradigms, usurped public power, adulterated traditions. Citizens, lacking these references of identity, of these traditional parameters, turned into a herd. Those who didn’t consent were executed or imprisoned, or went into exile, or were consumed in the silence of their inner exile.

The new generations grow up lacking supports, authentic models, rigorous archetypes of improvement. They set themselves to dissimulation, ostentatious and caricature-like loyalty to a spurious regime to obtain privileges that, in the majority of cases, are ridiculous, as much as or more than the stones of glass beads with which the Spanish once bought the gold of the Indians. The degradation of the people is universal. The material and moral condition of Cubans subjected to Castroism can be summed up in one word: miserable.

It’s worth asking: are these scraped together men and women, whose manner of speaking we sometimes don’t recognize, an essential and prominent part of the Cuban people? Are they, these descendents of slaves and of shopkeepers who have been exploited and conned for half a century in the name of a crazed project, our compatriots? Are these millions of individuals debased by the totalitarian administration who, deprived of archetypes, sink into amorality and skepticism, our brothers?

I, who have always believed and still believe in the validity of the national ideal that our great men of the 19th century handed down to us, don’t hestitate in answering yes. However much we can’t recognize ourselves in their voices, in their gestures, in their conduct, in their lack of faith in the nation, they are our flesh and blood, part of that people to which we belong in agony like an extension of our being and without with we would feel much diminished.

They, the Cubans of the other shore — as much as many who come to this one in the midst of the continuous shipwreck — have been disfigured by the actions of history, but they are still intimate and dear to us, like a substantial part of an entity that covers us and surpasses us, that roots us and explains us.

The future of our beloved country doesn’t have to be exactly like we have dreamed in this long exile. Maybe the sacred ways whose absence we have deplored so much will never again be restored. Traditions are altered with new ingredients, in the same way that languages transform and customs evolve. The catastrophe that has happened in Cuba, responsible for so much death and imprisonment and exile and debasement, is not something that we can erase like a nightmare in order to start over.

We have in front of us the bitter pill of the reformulation of what it is to be Cuban, which, of course, is not a task exclusive to us, those from this shore, built in absolute repositories of an invariable tradition and ready to impose it from the podium of some fabulous tribunal, but rather of all sorts of voices and individuals, with a variety of contributions and visions, of principles and objectives, of ambitions and compromises.

The transformations that a people can suffer — sometimes for the worse — in the history of their development are not susceptible to being ignored: neither the jurist, nor the politician, nor the philosopher, nor the historian can permit himself that luxury. If only certain things hadn’t happened!

But, as we well know, history is not what could have been, but rather what was, and its consequences are palpable. If we compare what happened in Cuba’s recent history with more drastic historical events, we can even find some basis for optimism.

Let’s think, for example, about the Spanish conquest of America and what its impact meant on indigenous cultures, the most advanced, because those of the Caribbean ended up simply abolished.

What profound trauma should the Incan and Aztec priests, princes, and poets not have suffered in face of that shock that destroyed their temples and their codes, dominated their languages, suppressed their gods and their hierarchic strata, and even changed their names? I’m sure that there were many members of those cultures who lived and died dreaming of the return of the old worship and of the restitution of their ancestral customs, of a worldview that by then was never to return.

Likewise, in Elizabethan England, how many would not have waited from a long exile, or from a fearful underground, the return of what they supposed was the true faith, the return of the monasteries and abbeys, the celebration of legitimate worship subject to the Roman pope, the return of that world, in short, that the frustration and anger of Henry VIII had undone? But in England there would be no new monasteries until 300 years later, and the Roman mass would never again be celebrated in the old cathedrals of the kingdom. So radical and definitive can certain changes be.

The French Revolution — that has been so exalted and venerated by militant republicanism — wanted to remake everything and, in a spirit of change, changed not only the configuration of the State, but even the name of the months of the year and the length of the week and, of course, the national anthem and the flag and the political division of the country and a thousand other things. France would not again be the same, nor would the rest of Europe and thus the whole world, thanks to that monstrosity of the revolution that was Bonaparte and despite the fifteen years of Bourbon restoration that followed his overthrow.

How many, how many — we think — lived and died in the France of the 19th century and even that of the 20th, dreaming of the return of the Ancien Régime, hoping that the hateful rosette that represented the shirtless ones and the regicides would be lowered once and for all, and that once again the lilies that had distinguished the French kings since the high Middle Ages would cover the countryside.

Fortunately for us, and despite the drastic process of transformation and deterioration that has taken place in our country in the last fifty-something years, the visible symbols that identify us have not seemed to change: the official name of the State hasn’t changed, nor the flag, nor the shield, nor the anthem. This isn’t much, certainly, but it’s something, a sphere of common understanding from which to start.

Neither have those in charge in Cuba rejected the place and the words of the founding heroes, especially that of José Martí, even though they have manipulated his doctrine and have wanted to make him an accomplice to infamy. Martí’s discourse on Cuba and his political vision — deeply democratic — can still serve to extend a bridge — precarious, but a bridge nonetheless — between these two shores of our fractured national identity.

There’s no room, it’s true, for excessive optimism nor for the triumphalist visions that sometimes encourage us. Cuba will not be waiting for us, in some moment of an improbable future, like a docile material on which to imprint the vision of our society, more perfect and idealized, additionally, than what never was; to realize the old dream of waking up sleeping beauty and finding that everything revives around it. That is not possible. That never, in history, has been possible.

However, neither does that reality leave us without a task. There is still a job to do, I believe, in face of this devastation that afflicts us. We preserve our vision. We’ve had time to ponder the weaknesses, political and social, that brought us, as a people, to this point of disfigurement. We still have a trace of enthusiasm and dedication, we are still repositories of civic knowledge that our people from over there — because they are part of us and our pain — have maybe forgotten, forced by the difficulties of their lives; or almost certainly reinvented amidst their atrocious circumstances.

Between us we have to return to reformulate Cuba when this nightmare ends, and even before it ends, from the very moment in which we plan to cross this abyss, with the contributions of all and the voices of all. Martí said it wisely: “from the rights and opinions of all its children is a people made, and not from the rights and opinions of a single class of its children.” How difficult it is to renounce, in front of the terrible uprooting, the grip of our truth, of our solutions, of our arrogant sufficiency, to acquire the generosity and humility that a common undertaking imposes!

Editorial note: Making the most of the debate over the Constitution and the Cuban people, we reproduce this text with the authorization of the author, who read it on November 23, 2010, at the Association of Cuban Ex-Political Prisoners of New York-New Jersey.

Translated by: Sheilagh Carey

_____________________________

The 14ymedio team is committed to serious journalism that reflects the reality of deep Cuba. Thank you for joining us on this long road. We invite you to continue supporting us, but this time by becoming a member of 14ymedio. Together we can continue to transform journalism in Cuba.

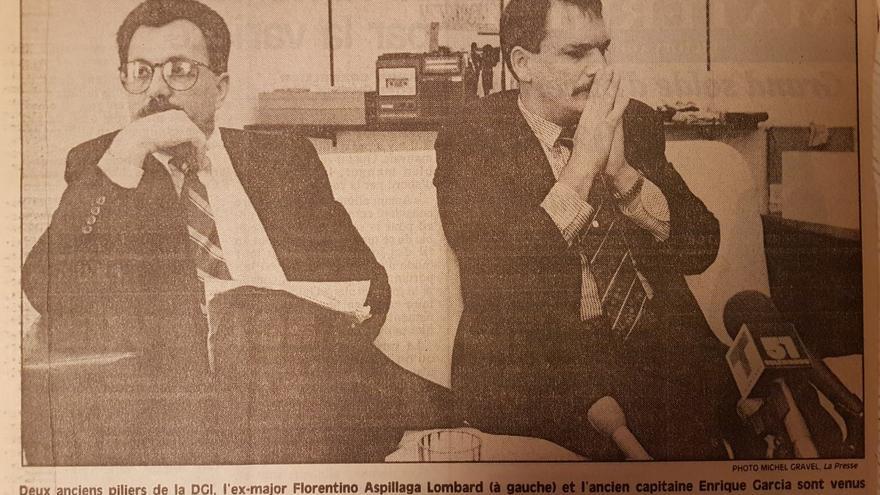

Luis Cino Álvarez, Cubanet, Havana, 5 November 2018 — The temper tantrum and bunkhouse scene put on recently by Castroism’s anti-diplomats, who grew indignant that the issue of political prisoners in Cuba was brought up at the United Nations, brought to mind a case of which I learned a few days ago via an inmate of Guanajay prison, of a young ex-officer of the Interior Ministry (MININT) who also is confined there, serving a 25-year sentence in terrible conditions.

Luis Cino Álvarez, Cubanet, Havana, 5 November 2018 — The temper tantrum and bunkhouse scene put on recently by Castroism’s anti-diplomats, who grew indignant that the issue of political prisoners in Cuba was brought up at the United Nations, brought to mind a case of which I learned a few days ago via an inmate of Guanajay prison, of a young ex-officer of the Interior Ministry (MININT) who also is confined there, serving a 25-year sentence in terrible conditions.