![]() 14ymedio, Zunilda Mata, Havana, 27 March 2019 — “Between the end of February and April I do ’the harvest of potatoes’,” jokes Jaime, the fictitious name of an illegal seller of the tuber, in conversation with 14ymedio. “Before, I used to sell shrimp and lobster, but this is less dangerous, because despite having to move larger volumes, it does not leave a trail of odor like seafood does, nor is it so controlled by the police.”

14ymedio, Zunilda Mata, Havana, 27 March 2019 — “Between the end of February and April I do ’the harvest of potatoes’,” jokes Jaime, the fictitious name of an illegal seller of the tuber, in conversation with 14ymedio. “Before, I used to sell shrimp and lobster, but this is less dangerous, because despite having to move larger volumes, it does not leave a trail of odor like seafood does, nor is it so controlled by the police.”

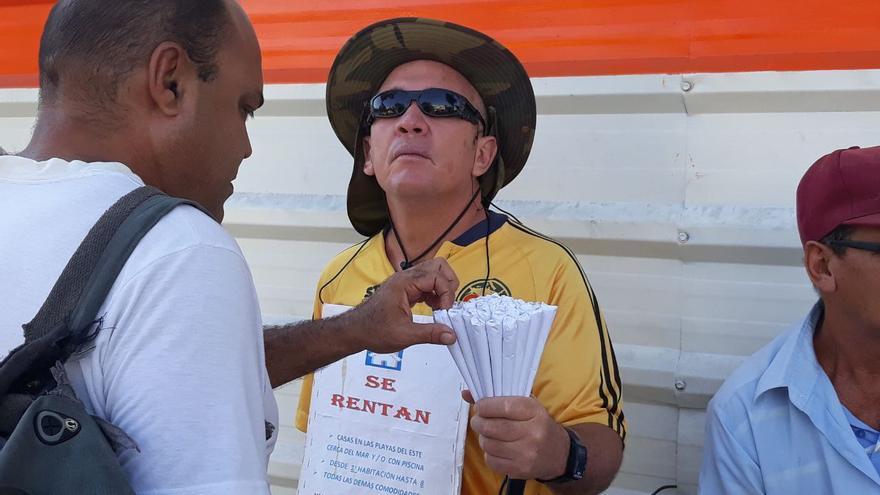

Five years ago, Jaime went to the 19th and B market in El Vedado in Havana to buy some yucca and ended up talking with an informal vendor who offered a bag with 5 pounds of potatoes for 1 CUC. “I realized right away that there was a niche market and I started looking for contacts to do the same.”

At that time, he says, he was lucky. “The price of the potatoes went up because they have been scarce, so that same bag I now sell for 2 and even 3 CUC, it depends on the type of customer,” he says. “I sell from home and I have my network of contacts that are basically paladares (private restaurants), foreign diplomats and Cubans who can spend more.” continue reading

“I have two supply routes, several guajiros from the San Antonio de los Baños area and also some stores where they sell potatoes on the ration book,” he explains. “Both are all the same to me, but right now all the supply I have comes from the markets, because right now the sale to the population has begun.”

“The supply” to which Jaime refers is nothing other than the diversion (i.e. theft) of state resources that end up for sale illegally. “The miracle of the surplus,” as Jaime calls it, is the sum of what is obtained by manipulating the scales or by adding dirt and, also, from the rationed amounts that people don’t pick up. “I make a living from that, getting those potatoes to people who can pay what they are really worth.”

Consumers buying through the rationed market receive a total of 14 pounds of potatoes in multiple deliveries, at the subsidized price of 1 CUP per pound. The supply arrives in the months of February and March when the so-called Cold Campaign is harvested from the fields. In other provinces the sale of the product tends to be lower quantities and sporadic.

The fall in potato production has been remarkable in recent years. In 1996, during the Special Period when it was strictly rationed, exports began after the harvest reached 348,000 tons. With the Raulista reforms, in 2010 its unrationed sale was authorized, but in just five years the harvest had fallen to 123,938 tons and the authorities had to import 15,233 tons to meet the internal demand. In 2017, the potato was again rationed.

“We have several dishes that can be accompanied with mashed potatoes and malanga,” says Rubén Núñez, an assistant chef at a restaurant located next to the central Boulevard of Havana. “It has been several years since we began using instant flakes to replace the natural potato and although it is not ideal, there is enough demand.”

“The packages with instant mashed potatoes are very cheap and easy to bring to Cuba from Miami, Cancun or Panama, and they weigh very little so we have a stable supply,” says this paladar employee. “The recipes with fries are made with pre-cooked and frozen packages that we buy in some markets in Havana, but our menu does not include any dish with boiled or roasted potatoes.”

According to Núñez, you have to get used to it. “You can find many substitutes to the potato, such as bananas, sweet potatoes and taro, but we get tourists who ask for natural potatoes and you have to explain that there are none and suggest another garnish to accompany the main course.”

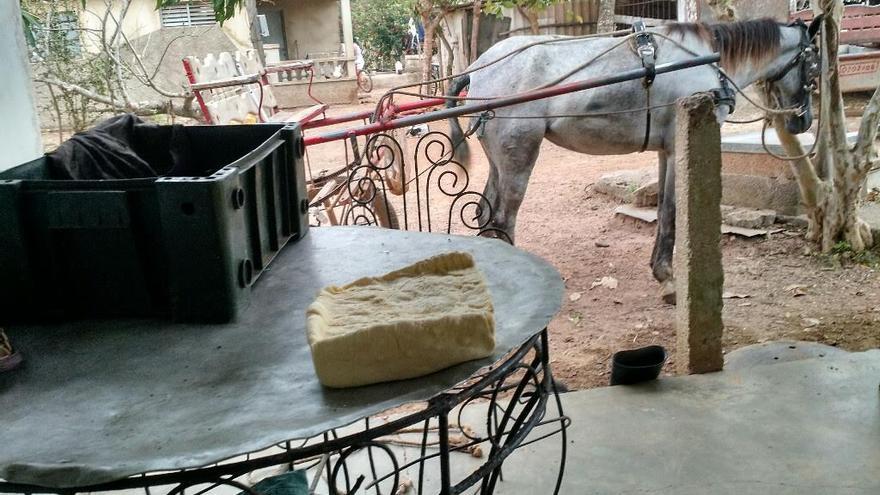

Luis Marrero was one of the first farmers in the area of Güira de Melena who joined the planting of potatoes when the state ended its monopoly on cultivation and distribution. “My father and my grandfather had planted a lot f potatoes at the beginning of the last century,” he tells this newspaper.

“That’s why when they allowed the farmers to buy the seeds to grow them, I immediately asked for the ’technological package’ that I needed,” he adds. In a state store he bought fertilizer sacks and the seeds necessary to achieve a good harvest.

“That first time I grew potatoes I was very happy because everything was very easy for me, although it is a crop that has its temperature demands,” he details. “I planted the Romano variety, which is quite common in this area and it went well, but over the years the purchase of the seeds became very complicated (as they call it in the Island when the tubers themselves have outbreaks) and the fertilizers have failed “

Over the years, Luis was reducing the area devoted to this crop because he thinks that the State pays the farmers “poorly for a quintal [101 pounds] of potatoes.” Most of the harvest must be sold to the State.

“We are paid between 45 and 65 CUP per quintal, it depends on the quality of the product but I can sell a pound at 3 CUP from the door of my house to the resellers who then sell them for twice that money,” explains the farmer. “It would be silly if I did not sell inthis way.” In this season Luis does not expect big gains. “I have not planted a lot of potatoes and if I take out about 1,000 or 1,200 CUP, it will be a lot.”

Until the beginning of March, 6,100 hectares of the tuber had been planted on the island and 7,200 tons had been harvested, of the 122,000 tons that are expected to be harvested in the provinces of Mayabeque, Artemisa, Matanzas, Villa Clara, Cienfuegos and Ciego de Ávila.

In view of this situation, the Government began, over a year ago, negotiations with Peruvian producers, who have surpluses. They do not seem to have reached an agreement. Meanwhile, the informal vendors continue with their business and the consumers with their packaged potato flakes.

___________________________

The 14ymedio team is committed to serious journalism that reflects the reality of deep Cuba. Thank you for joining us on this long road. We invite you to continue supporting us, but this time by becoming a member of 14ymedio. Together we can continue to transform journalism in Cuba.