Category: Yoani Sanchez

“Cuba Magazine” Style / Yoani Sanchez

Our apologies, we do not have subtitles for this video. Article 53 of the Cuban Constitution (referenced in the video) reads:

ARTICLE 53. Citizens have freedom of speech and of the press in keeping with the objectives of socialist society. Material conditions for the exercise of that right are provided by the fact that the press, radio, television, cinema, and other mass media are state or social property and can never be private property. This assures their use at exclusive service of the working people and in the interests of society.

Reinaldo speaks little of his time as an official journalist. When he does, it is with a mixture of frustration and relief. The first from his responsibility for the fabrication of so many stereotypes, and the second because by expelling him from the newspaper Juventud Rebelde (Rebel Youth) they turned him into a free man. Cuba International Magazine holds a prominent place in his memories, as he worked there for almost fifteen years.

In our house we have created an entire category of news with the name of this publication. When a provincial correspondent speaks on TV of the marvels of a battery factory — without mentioning how many are actually being produced — we watch, laugh, and say to ourselves: “This is in the worst style of Cuba Magazine.” If there is an article in the press presenting the life of a small provincial town through rose-colored glasses, we connect this, as well, with the editorial approach that has done and is doing so much damage.

Mayerín, unlike Reinaldo, just graduated from the Faculty of Social Communication. Sometimes he calls from a public pay phone to tell me about his latest article on a digital site he collaborates on. “Did you see,” he asks me, “what I managed to slip in in the third line of the second paragraph?” So I go check my reporter friend’s daring and find that instead of writing “our beloved and invincible Commander-in-Chief,” he has simply put “Fidel Castro.” Keep up your daring work!

Several generations of information professionals have had to approach their work through censorship, ideological propaganda and the applause of power. Sugarcoating reality, using national media as a showcase for false achievements and filling newspapers with a doctored and distorted Cuba, these are some of the evils of our national press. If these deformations leave a sour taste the mouths of readers and television viewers, the effect is even worse on the journalists themselves.

The informants end up prostituting their words to stay out of trouble or to earn certain privileges, and the social prestige of the reporter plummets and the press becomes an instrument of political domination. For this informant, who as a child dreamed of uncovering some scandal or investigating an event to its ultimate consequences, all he is left with is folding or breaking down the door, continuing to put make-up on reality, or being declared a “non-journalist” by the government.

6 February 2014

Antunez and His Wife Iris Released / Yoani Sanchez

From Paranoia to a Scream (Freeing Gorki “Last Time”) / Claudia Cadelo

PLEASE SIGN THE PETITION TO FREE GORKI THIS TIME

PLEASE SIGN THE PETITION TO FREE GORKI THIS TIME

By Claudia Cadelo De Nevi

On Friday night, after the release of Gorki and when we had already been to his house, he asked Lía if she had been to the beach. Well, it is simply impossible to narrate the last four days in two hours. He didn’t know yet that we had been at the court from eight in the morning, that we had been burned by the sun the whole day and that later two storms had rained on us… and that we were all there – the diplomats, the press and us (I say “us” because some of us didn’t know each other from before, so it was simply us, those who had been there).

I write this note because I want to share my experience in this act of solidarity that artists and non-artists (like me) have had with him and with ourselves, clarifying that I refer to physical artists, painters and writers, because I didn’t see a single musician, not even the most “underground” of the underground.

My friends call me a paranoiac; I am the one who lives in fear, who never opens the windows, who never speaks of politics, I am afraid of the dark, I don’t go out after ten at night, not even to the corner. But nothing had made me as afraid as I was for the last four days starting on Monday (and it still hasn’t left me). continue reading

However, getting to know people like Yoani, seeing her at my side with the banner in her hand, after having talked to her two or three times on the telephone, driven by faith, to see us all today helping Gorki, Ciro, Renay and Herbert, my friends holding the ground with me and rising to overcome our fears and doubts, with friends overseas moving heaven and earth and, finally, managing to convert a sentence of four years into four days… to me it still seems like a miracle.

I feel pity for those who haven’t called me, who have been hiding from me in case I might ask them for help, for those who said “yes” but didn’t come, I regret they haven’t experienced the happiness of the end, the sensation of having achieved the unachievable.

I believe today marks a turning point from “No we can’t” to “Yes we can.” We have shown that things can change, that we can stand up to injustices and the abuse of power and that fear is NOT infallible.

By Claudia Cadelo in Yoani Sanchez’s blog, Generation Y

31 August 2008

Brief chronology of a victory (Freeing Gorki “Last Time”) / Yoani Sanchez

How did it occur to us to go to a concert by Pablo Milanes to ask for the liberation of Gorki? That is something that has the trademark of the spontaneous and the haste of that which can not be postponed or thought better of. Ciro, Claudia and I talked about it among ourselves and immediately decided to do it because to organize or arrange actions too much is the fastest way for “them” to find out about it. None of us stopped to think about the repercussions of what would happen, because only he who has something to lose weighs his actions, with the same care that a housewife handles the tins in the market. continue reading

All photos below by: Claudio Fuentes Madan

Thursday before the concert.

Thursday, 28th, 7:30 p.m.

A group, among whom were Ciro, Claudia, Hebert, Emilio and me, met at the Coppelia bus stop to leave for the concert at the Tribuna Antiimperialista [Anti-Imperialist Grandstand]. At this time we were already being followed by some nervous boys of the political police and the police operation was impressive. It was still daylight and Pablo Milanés was singing when we arrived at the Protestómetro [Protest station]. We found a varied set of people there, including many military and some from the international press. For nearly forty minutes we were waiting for reinforcements but in the end we decided to take action without counting on those who were lost in the crowd, or who had never arrived, or who once there had changed their minds. The plan was to display two posters with the name of “Gorki” and to shout his name. That was meant to remind the musicians giving the concert that we had hoped for a pronouncement from them about the arrest of the leader of Porno para Ricardo.

Thursday, 8:35 p.m.

We are in the area to the left of the grandstand, as close to the stage as we can get and away from a group carrying thick sticks with their respective Cuban flags. Polito Ibáñez and Pablo Milanés had just finished singing “La soledad” [Solitude] and a brief pause gave us the opportunity for them to hear our shouts. At the count of one, two and three, Claudia and I displayed the fabric which lasted for just seconds in the air. I remember that we cried out, at least three times, the name of Gorki. People dressed in civilian clothes came out of everywhere and snatched the sheet painted with black spray paint. The women who fell on top of us were hefty ladies pulling our hair and shaking us. The men got the worst of it when the supposed “enraged people” doled out professional karate kicks to neutralize them. I remember the fear on the faces of the spectators who did not expect our action, and also the stampede of those who ran, leaving behind their shoes and the piece of the poster that I was able to keep in my hand. Ciro and Emilio were beaten and dragged into the security area at the side of the grandstand. Claudia managed to escape, as did Hebert, and I got away from a hand that grabbed me while calling for reinforcements. At the same time, a woman friend was arrested in the guest area for writing a paper asking Pablo for a few words of condemnation over the arrest of Gorki. We were never able to display the second sheet.

Thursday, 8:45 p.m.

The audience close to the incident dispersed and at the corner dozens of policemen began pulling up in trucks. Ciro and Emilio found themselves in the midst of mass of soldiers with batons and well built civilians who hit them repeatedly. Claudia and I met up and decided to leave the grandstand to connect to the internet immediately and relate what happened. The streets of Vedado had never seemed more inhospitable than on this Thursday night, with police stationed on every corner. We thought to ask for help, but at one house where we went they told us clearly that we had to leave. We then decided to separate with a premonition that it might be worse later.

Thursday, after 9:00 p.m., Claudia managed, thanks to the solidarity of some friends with internet access, to send a brief message that was the first chronicle of what happened as told by one of the protagonists. The message was very vague because we did not know then how many had been arrested or what was happening with them. The rest of the night we spent making calls and answering the questions of those who had already heard about it.

Thursday, after midnight, at almost one in the morning, Ciro called to tell me he had been released. During the more than three hours he was at the station at 21st and C, a member of state security wanted to impress on him that he knew everything about him, including that he had played on a football team. He told him that the arrest had been a misunderstanding and that the police intervened only so that the “people” wouldn’t lynch us. He argued that the people in the audience had thought we were going to display a counterrevolutionary poster and because of that we had been surrounded. Strange people that on the one hand can’t distinguish between a short name and a slogan, but are expert in the martial arts.

During the early morning we made telephone calls to other friends and musicians telling them to arrive early at the Popular Municipal Court at Playa. I believe that no one could sleep in the hours between the release of Ciro and Emilio and arriving at the corner of 94th and 7th Ave. The blows hurt more away from the heat of the action, but the fear subsided.

Friday 8:20 a.m.

A dozen friends were already stationed at the door of the court by the time I could sneak into the area that, since early in the morning, was surrounded by an intense operation. It seemed as if those who were there were dangerous armed terrorists, because nothing else could justify so many members of the Apparatus [State Security] on every side. I could see one of those who followed us the night before and realized that Operation Gorki was of the greatest importance for them as well. Looking at these nervous members of State Security, I always ask myself if we couldn’t include in their curriculum a course on managing better camouflage. It’s that they all resemble one another, with their perfect crew cuts, their wide shoulders, and their checked shirts or striped pullovers. Has no one told them that from every pore they look like soldiers in civilian clothes? In the academy, aren’t they warned that their grim looks, such serious faces and their total lack of swing, reveals their covert work? Please, can someone give them training to appear as simple, ordinary people.

Friday from 9: 00 a.m. until 6:00 p.m.

The foreign reporters were everywhere, and also some diplomats and a group of friends came by the score. I regretted the absence of the Cuban artistic community, especially the musicians who should have been there to support their colleague. However, I was not surprised that no rapper, troubadour or reggaeton artist appeared outside of the court. Many were not informed, and others weighed the loss of small privileges as too high a price to pay for a punk singer who had been previously convicted. Some friends who tried to reach the site were stopped by the police siege. The presence of the artist Sandra Cevallos, who has already repeatedly faced the hairy arm of censorship, stood out. Some of the faces I found there were the same as those from the outskirts of Casa de las Américas [House of the Americas] on January 30th, the day of the debate of the intellectuals. It appears that there are some people accustomed to protesting in front of all the doors.

The lawyer, a very young man, had been hired just two days earlier, after the repeated refusal of several lawyers to take over the case. The crime was the previously announced pre-criminal dangerousness and they blamed all the delay in starting the trial on the fact that the file had not arrived. Gorki’s father, a man of 75, appeared very nervous and the police guarding the court would respond to questions only from him. Several young defendants charged with the same offense were tried while we waited. I remember a thin mixed-race man who left in handcuffs and on seeing the cameras and microphones hit upon this to say, “As far as is known, we condemn people for taste.” I do not know whether the foreign press was able to film his words, but I want to record them here because I expect that by his gesture of courage he will have won retaliation.

Under a pine tree on the sidewalk in front of the Court was the group of friends. Emilio showed his blows and his teeth that had been loosened the previous night, while my mobile phone did not stop ringing with calls from all over the world. Ciro responded to journalists and a national television camera filmed everything we did. A very young girl, who was there without her parents’ knowledge, told me worriedly, “If we are on the Roundtable television show this afternoon, I don’t know how I’m going to explain it to my mom.” I thought of my son, waiting at home, away from the blows, the police, the injustice, confident that his mom would return and Friday would be another normal day. Remembering Gorki, his father, his daughter Gabriela, who at some point would be informed, I sat tight in the street and shook off the fatigue, the sadness and the fear, that never completely dissipates.

Despite being surrounded by the “compañeros of the checked shirts,” the presence of the international press protected us. How times have changed, I told myself, seeing the care taken by the police not to charge us, in front of the cameras. Even so, to see the foreign correspondents confirmed that I’m not made of the right stuff to be a journalist. I cannot stay behind the lens without getting involved. This work of entomology that consists of observing and reporting, but not intervening, is definitely not made for me. Being a blogger I can also be a part of what’s happening, so I am stuck with this role.

Deferring the start of the trial appeared to be a maneuver to test the stamina of those of us waiting outside the court. Planned for nine o’clock in the morning, the trail actually began around 6:30 in the evening. In this time some had left, others joined us, and a couple friends looked for something to eat. The informal market also benefited from our wait, because a lady managed to sell to us, despite the police fence, popcorn, cookies and potato chips. We had our rain shower at four in the afternoon and when the sun began to set we looked like we had spent the entire day at the beach. The point of no return had happened at noon and after that hour no one moved from there.

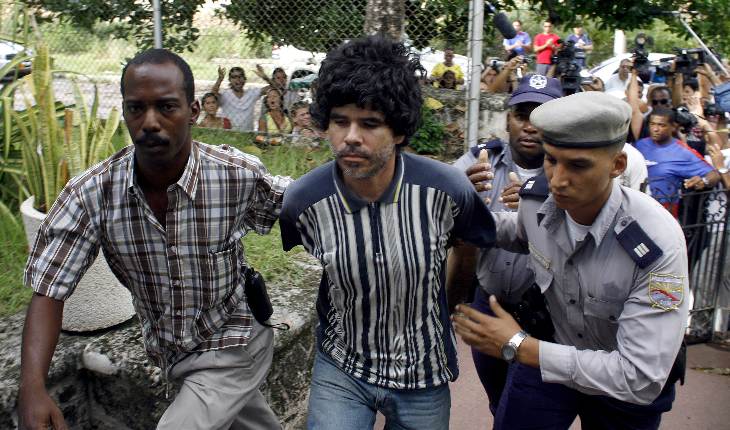

When the time approached for the arrival of Gorki, the men stationed at the corners began to close the fence. Maybe they thought we were going to attempt a daring rescue or something like that, but in reality we had reached an agreement to applaud and shout the name of the accused when he appeared. The police cars parked and security rushed to close a circle around him. Still, the foreign press was able to capture his face with a four-day beard, the handcuffs, and the shout of “Gorki” that resounded on the corner. The tension was palpable on every face but, without bragging, “they” were more nervous.

6:00 p.m.

The trial: I managed to enter the courtroom, next to Ciro, Claudia, Emilio, Diego Ismael and his girlfriend, Elizardo Sanchez and his wife Barbara, Francisco Chaviano, Gorki’s father Luis, Alexander the photographer, Javier, Claudio, Rene Esteban, and others whose names I don’t know and a pair from security who were stationed in a corner. The hall was nearly full when we entered because they had also summoned the relatives of a young man who would be tried later. The judge, a young woman, called for calm and presented the case. We learned at that time that the offence had been changed to “disobedience.” Gorki did not know if the punishment for that crime was more or less, but it mattered little: the circus had begun.

Under the gaze of a bust of Marti and with the national shield present, the first witness for the prosecutor appeared, the Head of Sector for the zone where Gorki lives. A brown man, with an accent from the eastern part of the country, he appeared very confused in front of all the press and the surprising support for Gorki he could see in the room. The police argued that the practices of the group bothered the neighbors and that they had already worked “preventatively” with the accused. The next witness was the former head of sector, who confirmed the testimony of the previous witness and emphasized that the rocker was a recidivist. Finally, they called a lady named Heidi to testify. A face marked by bitterness came into the room and identified herself as the President of the zone of the CDRs [Committees for the Defense of the Revolution] and a member of the Preventative Commission formed by the leaders of the block. When they asked her about Gorki’s social behavior, she warned that he “did not participate in the activities of the CDR, did not guard and did not vote… his social conduct can be summarized as making noise with his music and bothering the neighbors.”

The young defense lawyer stuttered before the “hot potato” in his hands, but managed to submit a letter from Gorki’s workplace confirming his employment. The prosecutor then asked for a monetary penalty for the accused and everyone breathed a sigh of relief. Six hundred Cuban pesos was the fine set; anyone would pay any amount, with their eyes closed, to not have to be in prison even one hour. The trial had ended and we felt all the exhaustion of the two days come over us.

The police “kindly” took Gorki in the patrol car to collect his personal belongings and then took him home. Outside we felt like jumping up and down and shouting his name. We left there in a group because we knew that if we separated “the boys of the batons” might dare to go after us. Fifth Avenue was the scene of joy, pats on the shoulder, contained laughter, and retelling of everything that had happened. We arrived at Gorki’s house and he had already shaved his grey beard. A bottle of rum left a backpack and fatigue mattered little, nerves were calmed, and the rocker’s father asked if we wanted to “kill his son.”

We had succeeded, Gorki was with us thanks to all those who were mobilized outside and inside. To those who signed the letter demanding his freedom, to the reporters who spread the word of his incarceration, to the sign ripped in seconds but recorded for years, in summary, thanks to the strength and the cry of thousands of citizens, organized spontaneously and confronting a machinery that is not accustomed to give ground. The boiling oil of the authoritarian, secretive and ideological judicial system was left with the desire to fry Gorki. We proved that if we engage in such actions more often, others could also walk free on our streets.

Yoani Sanchez from her blog Generation Y

31 August 2008

Operation Cleansing / Yoani Sanchez

Infanta and Vapor Streets, eight at night. The scaffolding creaks under the weight of its occupants. The area is dark, but there are still two painters passing their brushes over the dirty balconies, the facades, the tall columns facing the avenue. Time is short, the 2nd Summit of the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) will start in just a few hours and everything should be ready for the guests. The streets where the presidential caravans will pass will be touched up, the asphalt addressed, the potholes and poverty hidden. The real Havana is disguised under another stage-set city, as if the dirt — accumulated for decades — was covered by a colorful and ephemeral tapestry.

Then came the “human cleansing.” The first signs of one more stage set being erected comes via our cellphones. Calls are lost into nothingness, text messages don’t reach their destinations, nervous busy signals respond to attempts to communicate with an activist. Then comes the second phase, the physical. The corners of certain streets teem with supposed couples who don’t talk, men in checked shirts nervously touching their concealed earphones, neighbors set to guard the doors of those from whom, yesterday, they asked to borrow a little salt. The whole society is full of whispers, watchful and fear-filled eyes, a huge dose of fear. The city is tense, trembling, on alert: the CELAC Summit has started.

The last phase brings detentions, threats and home arrests. Meanwhile, on TV the official announcers smile, comment on the press conferences and carry their cameras to the stairs of dozens of airplanes. There are red carpets, polished floors, tree ferns in the Palace of the Revolution, toasts, family photos, traffic diversions, police every ten yards, bodyguards, accredited press, talk of openings, people threatened, dungeons filled, friends whose whereabouts are unknown. Not even the Ñico López refinery is allowed to let its dirty smoke leave the chimney. The retouched postcard is ready… but it lacks life.

Then, then everything happens. Every president and every foreign minister returns to their country. The humidity and grime push through the fine layer of paint on the facades. The neighbors who participated in the operation return to their boredom, and the officials of #OperaciónLimpieza — Operation Cleansing — are rewarded with all-inclusive hotels. The plants installed for the openings dry up for lack of water. Everything returns to normal or to the absolute lack of normality that characterizes Cuban life.

The fake moment has ended. Goodby to the Second CELAC Summit.

28 January 2014

What’s-his-name? / Yoani Sanchez

A crowd was waiting outside the mansion in Vedado with a statue of Abraham Lincoln in the garden. The language school opened its doors to new registrations and in the days that followed tested the attitudes of those interested. Everyone waited nervously, thinking that they would be evaluated on a pronunciation here… a mastery of vocabulary there. To our surprise, the main questions weren’t about language, but rather alluded to politics. By mid-morning a young woman who had been rejected warned us, “They’re asking the name of the first secretary of the Cuban Communist Party (PCC) in Havana.” We stood there mouths agape, who would know that?

A crowd was waiting outside the mansion in Vedado with a statue of Abraham Lincoln in the garden. The language school opened its doors to new registrations and in the days that followed tested the attitudes of those interested. Everyone waited nervously, thinking that they would be evaluated on a pronunciation here… a mastery of vocabulary there. To our surprise, the main questions weren’t about language, but rather alluded to politics. By mid-morning a young woman who had been rejected warned us, “They’re asking the name of the first secretary of the Cuban Communist Party (PCC) in Havana.” We stood there mouths agape, who would know that?

A few decades ago the leaders of the so-called “political and mass organizations” were figures known throughout the country. Whether through their excessive presence in the official media, long tenure in their jobs, or simply because of personality, their faces were easily identifiable, even to kids in elementary school. We relentlessly heard talk of the secretary of the Young Communist Union, saw on every newscast who was leading the PCC in a province, or overdosed on declarations from some president of the Federation of University Students. There they were, clearly recognizable. Some even came to have nicknames, along with numerous jokes about their quirks and inefficiencies.

This morning on national television they mentioned Carlos Rafael Miranda, national coordinator for the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDR). And it started me thinking about how blurred these positions have come to be, posts that before seemed to have so much power to decide the fate of so many. People now unknown leading institutions that every day fall deeper into indifference, are more forgotten. Leaders whose led can no longer remember their exact names and surnames. Figures who came too late to stand in the flashes of the camera, to be included in the analyses of the Cubanologists, or — at least — to be the targets of some joke. Mere shadows of a system where charisma is increasingly scarce.

25 January 2014

Kapuscinski and Walls / Yoani Sanchez

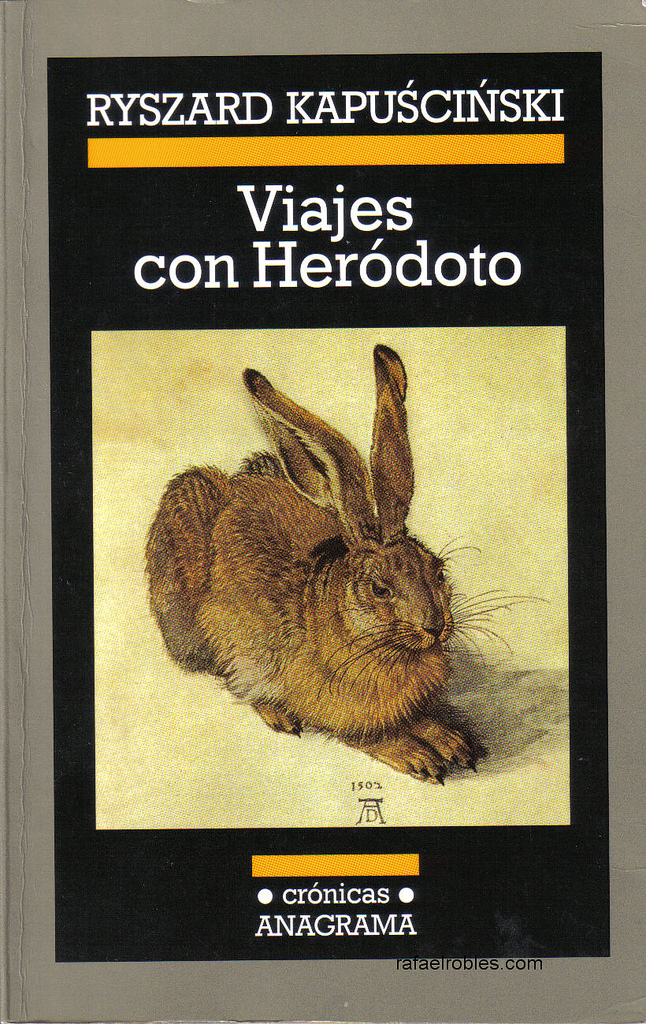

That house had a protective fence bristling with iron spikes, and the one next door had a huge gate and double locks. On the doors of certain offices signs warn, “Authorized Personnel Only,” and around the Council of State the armed guards are stationed every ten yards. Protecting themselves from others, avoiding contact, keeping strangers out, are the objectives of these physical and legal parapets. They are just like what the masterful Ryszard Kapuscinski described in his article, “Chairman Mao’s One Hundred Flowers,” during his trip to China.

In this vivid and sharp text, the Polish journalist brings us the human mania to construct obstacles to separate us from the different. The perfect example is that serpent of bricks, stones and various materials that snakes across the geography of the great Asian giant. All to defend itself — or isolate itself — from those who were left on the other side of the wall. In the Cuban case, it has been simpler, because the sea distances us from the rest of the planet. A strip of salt water that has marvelously served the political discourse of a “people under siege” and “the enemy” on the other shore. All out of fear, out of pure fear of diversity.

Kapuscinski reflected on the human and material costs of the construction–real or discursive–of walls. An exercise we could try in our own country. How much has isolation cost us? How many resources have been spent on trenches, tunnels for war, aggressive diplomatic campaigns, indoctrination in schools to foment the idea of a foreign enemy? How many lives have been destroyed, diminished or terminated because of these walls erected for the benefit of a few? “The wall serves not only to defend oneself… it allows one to control what happens within it,” reads Travels with Herodotus, and it’s painful that sixty years later it continues to be a reality in so many places.

24 January 2014

Oscar Biscet Under House Arrest

Oscar Elias Biscet Arrested

Zeal and CELAC / Yoani Sanchez

A friend called me yesterday. He was nervous. All around his house the police were engaged in an intense “cleansing.” The reason for such concern was that this retiree with no pension has an illegal satellite antenna with which he provides TV service to several families. So, when the forces of order get strict, my friend has to cut the cables, hide the dish and give up the service fees he earns for several days. A real economic disaster for him. Whenever he hears about an international summit, a meeting with invited foreigners, or some dignitary visiting from another country, he starts to fear for his business. He knows that each of these events corresponds to a police raid carried out with zeal and intransigence.

When Pope Benedict XVI visited the Island, hundreds of beggars, prostitutes and dissidents were “taken out of circulation.” The phone company, Cubacel, also did its part, cutting service to 500 users across the country. Now, the second Summit of the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) is coming our way, to be held in January in Havana. Already truckloads of flowerpots have appeared, with plants that will be watered only for the two weeks they are located along the main avenues. In some central streets scaffolding is rising, with housepainters who are coloring over the cracked and blackened walls. They are also retouching the traffic signals along the route where the guests will pass, and even the old chipped billboards are being replaced by others.

The clandestine and officially “unpresentable” Havana has been warned that it must be quiet, very quiet. The beggars are being held until the Summit is over, the pimps warned to maintain control over their girls and boys, while members of the political police visit the homes of the opposition. The illegal market is also being held in check. “Calm down, let’s have a little calm,” the police repeat in a threatening tone, without ever leaving written notification. So my friend started this morning. He is disconnecting his equipment and called me again to assure me that on the 28th and 29th he won’t even think of putting a foot in the street. “Not at all! I have no desire to sleep in a dungeon,” he told me, before hanging up the phone and locking away his antenna.

23 January 2014

“Be very quiet…” / Yoani Sanchez

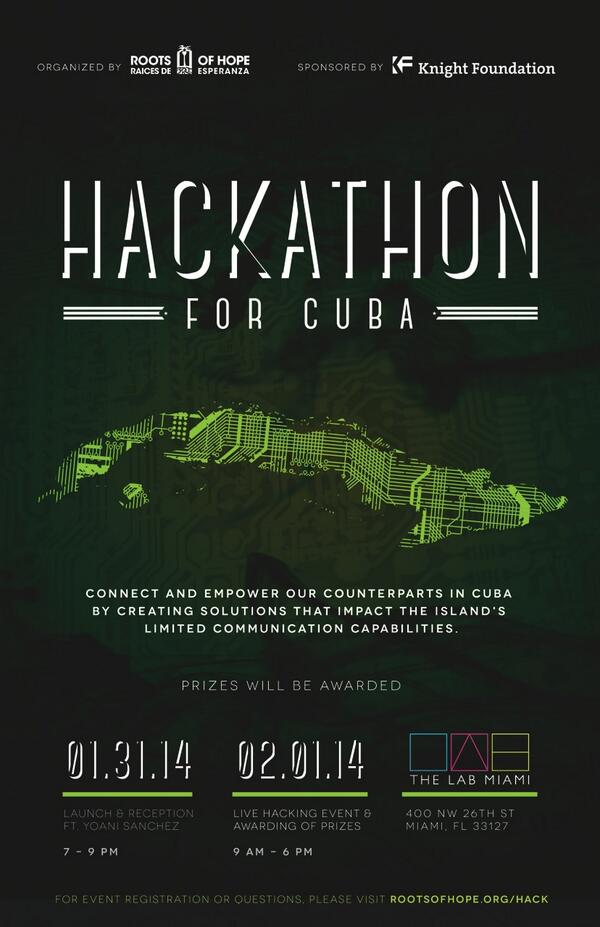

Hackathon for Cuba with Yoani Sanchez

One Year of Immigration and Travel Reform and… What Changed? / Yoani Sanchez

This time she couldn’t enter the terminal to watch him leave. A sign warns that the interior of José Martí International Airport can only be accessed by travelers, not their companions. So she said goodbye at the door. He is the second son who has left since Immigration and Travel Reform was implemented a year ago. For her, like so many Cubans, it’s been a year of goodbyes.

In the first ten months of 2013 some 184,787 people traveled outside the Island. Many of them for the first time. Although the official statements try to deny that people flee the country, more than half of all travelers hadn’t returned as of the end of November. Nor do we need the numbers. It’s enough for each of us to just look around to quantify the absences.

From the personal and family point of view each trip can transform a life. Whether escaping for good from a country where you don’t want to live, learning what exists on the other side, rediscovering relatives or simply some time away from the daily routine. The question is whether the sum of all these individual metamorphoses serves to change a nation. The answer — as with so many things in the world — can be a “yes” and a “no.” continue reading

In the case of Cuba, the departures have served, in part, as an escape valve for the dissent. The most rebellious sector of society packed its bags to leave for a short or a long time. The government took advantage of this and also of the material benefits of the journeys, which result in more remittances sent, more imported consumer goods, and more airport taxes collected. The smokestack-free travel industry.

For civil society activists who took international tours, the opportunity was extraordinary. Bringing their voices to places where, before, only officialdom was heard, has already been a good step forward. They have been able to get closer to the topics debated in the world today and this has helped them to modernize their approaches, to better define their civic role and to involve themselves in issues that transcend national frontiers.

During all this time, however, they have refused to let the former prisoners of the Black Spring travel outside the country. Also the number of exiles blocked from entering Cuba has maintained an upward trend. Lamentably, after the huge headlines announcing Decree-Law 302, those dramas did not find sufficient coverage in the international press or organizations.

A good part of the population still can’t afford a passport. For all these Cubans, the Immigration and Travel Reform takes place only in the lives of others, on television screens, or in the pages of newspapers. Coincidentally, this is the same sector that still has not been able to contract for a mobile phone, stay in a hotel, or even peek into the markets for houses and cars.

So 2013 was a mix of suitcases, goodbyes, returns, names added to phone directories, sighs, long lines outside the consulates, reunions, listings of homes for sale to pay for airplane tickets… A year for leaving and a year for staying.

13 January 2014

The Ten Most Popular Android Apps in Cuba / Yoani Sanchez

There’s a green robot with antennae everywhere you look. In the mobile phone repairers’ ads, on certain nice T-shirts, and even staring at us from the windshields of some cars.

There’s a green robot with antennae everywhere you look. In the mobile phone repairers’ ads, on certain nice T-shirts, and even staring at us from the windshields of some cars.

Not only does the Android app show up in many places in Cuba, the Google operating system has also grown in popularity over the last year. The creature based on Linux lives in a good share of the smartphones entering the country, legally or illegally.

If we take a look at what’s inside these Smartphones, we note the prevalence of applications that work off-line. Local users prefer those that work without access to the Internet, to ease the limitations of living on the “Island of the disconnected.”

There is a great demand for maps throughout the country, encyclopedias with images, translators into various languages, role-play games and tools for everyday life.

After inquiring among several users and cellphone repairers, I can offer a list of the ten most popular Android applications in Cuba.

WikiDroyd: A version of the well-known interactive encyclopedia Wikipedia, which includes not only the texts but the images. It works without an Internet connection, although it must be downloaded to the phone’s database. If you just ask the technician, it will include the version most used in Spanish with almost two gigabytes of data. continue reading

EtecsaDroyd: A pirated copy of the telephone directory from the Cuban phone company ETECSA. It has the complete name, identity card number, and even the home address of each subscriber. Although this information should be protected and not for public use, every year it’s leaked and ends up on the computers and phones of thousands of people. One more example of the many prohibited things that so many Cubans do.

WiFi Hacker: A tool for hacking WiFi networks and getting free access to the web. It may seem somewhat useless in a country where there are few wireless connections to the Internet… but you never know.

Revolico: An unauthorized version of the ad site Revolico.com. With a simple interface, this app lets you download the ads for buying and selling things in different categories. It has spread rapidly, given the growing illegal or alternative market versus the extremely expensive and poorly stocked State markets.

Go SMS Pro: A magnificent messaging utility to send SMS and MMS text messages. Much better than the native Android application for this use. Clear background, multiple themes to change the graphic interface, spell-checker and even a nice pop-up configuration that alerts you to new messages coming in.

ASTRO File manager: Lets you manage the files on a cellphone or tablet. For those who like to search in folders or directories, this applications helps with that task. Delete, copy, rename and find files, all with just a few clicks.

Photo Studio: Crop a photo, apply a nice color filter to it, or simply retouch it, it’s never been so easy. You have the option of taking a high-definition photo and reducing it to a size you can send by text MMS (Multimedia Messaging System), which in Cuban only accepts images of about 300 kilobytes.

OfficeSuite Pro: For those who take their office with them everywhere this is a magnificent tool to write, make notes and jot down ideas that come to mind in the most amazing places. It allows you also to create and read files in Excel, PowerPoint and Adobe Reader.

Linterna (Flashlight): In dark theaters where there are no ushers or on unlit stairs, this simple flashlight will save you from tripping. With features like this we see that a phone can also work in a very simple but essential way.

OsmAnd: This is one of a series of very valuable applications that offer offline maps. Others include OruxMaps, City Maps 2Go, MapDroyd and Soviet Military Pro. Although GPS satellite service is not available, a pretty good geo-locating function works through triangulating off cellphone towers. It includes really detailed street maps of the principal Cuban streets, but in rural areas the road descriptions are not as accurate. In a country with badly signed roads and streets… this tool is almost a miracle.

10 January 2014