![]() 14ymedio, Serafín Martínez, Havana, 9 March 2021 — The times when all the burners were lit in a kitchen or of simmering beans for hours are over for many Cubans. Increases in the rate of manufactured gas has redesigned culinary practices and has also put in check the families who cannot pay the new prices, in force since January.

14ymedio, Serafín Martínez, Havana, 9 March 2021 — The times when all the burners were lit in a kitchen or of simmering beans for hours are over for many Cubans. Increases in the rate of manufactured gas has redesigned culinary practices and has also put in check the families who cannot pay the new prices, in force since January.

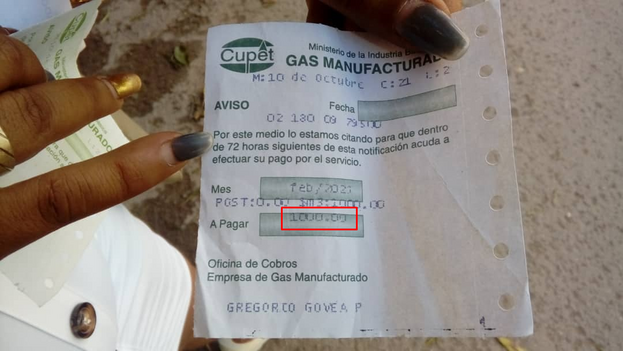

Enma Quiala Povea, 31, a single mother of three and pregnant with another, does not know how she will be able to pay the cost of the “street gas” that she supposedly consumed during the second month of this year. She just received a 1,000 pesos bill, more than 50 times what she paid last December, and she gets social aid that barely covers the purchase of basic products.

As of January 1st, 2021, and as part of the Ordering Task, the cost of manufactured gas service increased from 0.11 pesos per cubic meter to 2.50. However, the increase is part of a package of increases that also includes new costs for electricity, transportation, and products from the rationed market, which further strains people’s pockets. continue reading

Quiala, a neighbor who lives at Velázquez #514, between Guanabacoa and Melones, in Luyanó, Havana, explains to 14ymedio: “I live with my father and my children and we usually pay between 14 and 19 pesos a month for the gas bill, which is a hundred and some cubic meters per month according to the meter reading”.

Surprisingly, “this February, the gas reading according to the meter rose from the usual one hundred and some cubic meters to 400. That seems impossible, because my father is a Covid essential worker who is always mobilized and there was no additional consumption”

Surprisingly, “this February, the gas reading according to the meter rose from the usual one hundred and some cubic meters to 400. That seems impossible, because my father is a Covid essential worker who is always mobilized and there was no additional consumption,” claims the woman.

“I am aware that if I had spent it, I would have to pay for it, but I am not going to pay 1,000 pesos to allow a collector’s error. I receive 2,860 pesos from social assistance to take care of my children, which is not enough for my living expenses, and I cannot work outside my home. I can’t afford all that money in gas”.

While other rates such as electricity, the cost of contributions to the official press and liquefied gas have been ‘rectified’ after popular complaints, the price for manufactured gas that is consumed in Cuba, especially in Havana, has remained as established in the new economic adjustment policy.

“We are two adults and two children here,” Moraima Ríos, a resident of the Cerro municipality in the Cuban capital, explains to this newspaper. The youngest of her children has cerebral palsy and is bedridden, requiring continuous care, special food preparation and hygiene requiring high gas consumption.

“In this house, our income has practically not changed, because although the fees for the mechanical services my husband performs as a business owner have increased, the resources he needs for his work have increased as well, so now his earnings are practically similar to before but we pay more for everything, including gas.”

“I had to go to complain, but before doing so, I needed to pay the bill, because they told me that the case cannot be reviewed unless the bill is paid in full.”

During the month of February, the family received a bill for 1,260 pesos for the consumption of manufactured gas that month. On the street where they live in the Cerro neighborhood, most of the neighbors “got the same surprise” when they reviewed their accounts. “I had to go to complain, but before doing so, I needed to pay the bill, because they told me that the case cannot be reviewed unless the bill is paid in full.”

Since March began, Ríos barely lights the stove. “I have become afraid of the kitchen because one does not know how much the gas bill will be later,” she explains to this newspaper. “With these cold days I have had to prioritize heating the water to be able to bathe my son, but I cannot turn on the oven in the kitchen or do anything that is not basic”.

When she went to claim the February invoice, a worker from the Manufactured Gas office, managed by the state-owned Cuba-Petróleo warned Ríos that “the country is going through problems with manufactured gas and she needs to save,” so the rise in price was going to “help avoid waste”.

However, the head of domestic fuels at Cupet, Lucilo Sánchez, recently assured the national press that “there are no difficulties” for consumers of manufactured natural gas, which is processed from existing oil deposits in Cuba’s north western strip.

Cuba produces 3.5 million tons of oil per year (22 million barrels), of which 2.6 million tons (16.3 million barrels) of crude oil and approximately 1 billion cubic meters of natural gas are obtained, covering 97% of what is used to generate electricity and domestic gas consumption in Havana.

“I do not understand that one day they say that manufactured gas is guaranteed and that most of it is produced nationally, and the next day they charge us these prices,” claims Ríos. “I can understand that this happens with an imported product, such as food that is not produced in Cuba, but this is something that comes from our own soil, which is owned by the people.”

“Since the new rates for manufactured gas were established, there has been a notable increase in the influx of customers”

At the Cupet office for collections to the population at Paz Street in the municipality of Diez de Octubre, an official acknowledges the problem. “Since the new rates for manufactured gas were established, there has been a notable increase in the influx of customers,” she says.

The employee, who prefers to remain anonymous, insists that the high bills are mainly due to customer ignorance and to bad practices in the daily use of gas. “The population has not become familiar with the new tariff of the Ordinance Task of 2.50 pesos per cubic meter of manufactured gas, where there are meters installed”.

“It will take them time to adjust, but each case will be analyzed promptly. If a customer does not have money to pay, they can request the presence of an inspector to check for leaks. But in the end, you will have to pay for your consumption because the objective is to eliminate undue freebies and promote energy savings and efficiency in the population”, advises the employee.

“If I pay this money, I don’t have anything left to buy food for my children, but if I don’t pay, I run out of gas to cook the food they need. What do I do?” Moraima Ríos wonders. “While I make the claim and they check my meter, I run out of money for everyday expenses.” The solution that she has created for the moment is “to trash some of her furniture and build a wood fire in the yard”.

And she concludes: “The neighbors are already complaining about the smell of smoke, but I don’t want to use gas at those prices and with those surprises. Nor the electricity, either, which is also very expensive”.

Translated by Norma Whiting

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.