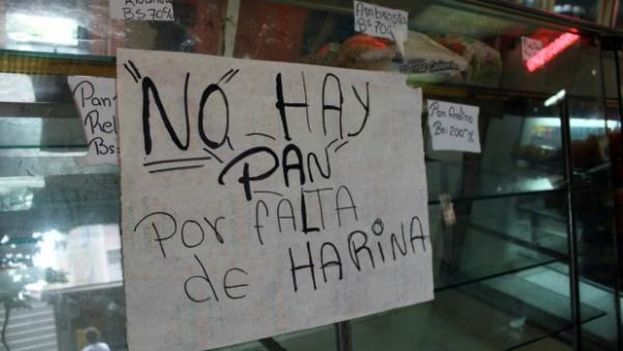

![]() 14ymedio, Rolando Polea, Caracas, 15 September 2016 — It’s 6:00 am on June 28, I drive slowly along the Panamerican highway, my view lost before the long line of people in shelters between the fog, the drizzle and hunger. Pressing up against each other as if for warmth. Almost a mile separates the last person in line from the entrance to the supermarket. It is the same image as the previous day. Everyone is waiting for the store to open so they can buy any regulated product that arrives, no one knows what, nor do they know how many they will be able to buy, much less if any product will show up at all.

14ymedio, Rolando Polea, Caracas, 15 September 2016 — It’s 6:00 am on June 28, I drive slowly along the Panamerican highway, my view lost before the long line of people in shelters between the fog, the drizzle and hunger. Pressing up against each other as if for warmth. Almost a mile separates the last person in line from the entrance to the supermarket. It is the same image as the previous day. Everyone is waiting for the store to open so they can buy any regulated product that arrives, no one knows what, nor do they know how many they will be able to buy, much less if any product will show up at all.

And the agents of Venezuela’s “Bolivarian” National Guard have arrived, dressed in their usual olive-green uniforms and some Robocop protectors, who with rifles, helmets and shields, monitor the line. continue reading

I step in front of the closed door of the supermarket, flanked by the big truck of the anti-riot troops, only to notice that on the other side, extending for about 700 yards, is another line made up of the elderly. Many young people among them, these are the “liner-uppers,” family members, grandchildren, children and people who hold other people’s places.

It’s hard to get rid of that metallic taste left by the “shedding” of dignity.

Suddenly my mind, which strives to focus on the road and the radio to forget the tastelessness, is dejected by a call to the radio station, a complaint, from a lady who speaks, more words, less words, warning about the irresponsible favoritism of the officials charged with the sale and control of regulated products, allowing certain categories of public officials – like firefighters, doctors or security agents – to go ahead of the other public employees, a situation that doesn’t seem fair.

Almost immediately a “public official” calls the radio station, specifically a firefighter, to call the lady’s attention to the fact that his work saving lives and the long shifts make it impossible “to stand in line for 10 hours” to buy the regulate products of the basic market basket, and he demands that the woman complaining have some “understanding and civility.”

In the space of hardly a breath, the newscaster takes another call in which a “public employee” takes the firefighter to task, insisting he recognize that the difference between “officials” and “public employees” is governed by an internal scale in the government structures, but that eventually “everyone has the same right”…

The diatribe ends with the silence of the newscaster, and then a brief, “There you have a complaint for the authorities to consider,” followed by music, just music. What more can be added.

I think that in the midst of this whole string of unhappy complaints it’s worth remembering the public employees who, while a firefighter, police office or even a Bolivarian National Guard, work long and arduous shifts, whether saving us or repressing others, they simply, for the most part, “suck lives.”

Amid the government inefficiencies, there are some few employees or officials whose mystique and honesty are shrunk in the morass of corruption and bureaucracy. My acknowledgement, congratulations and honor to those heroes who survive that oasis in a desert of the convinced.

How far did the class struggle go… destroying the historical materialism of Marx and the classes in the productivist terms of Max Weber, the founding fathers of modern sociology, they should be appalled, the war of the proletariat.

What was heard had to have deep roots in the thinking of modern Venezuela, the misery of the totalitarian state, in which, after the ruin and disappearance of virtually all private initiative, is all that’s left standing.

Its inefficiency has plunged the country with the largest oil reserves in the world, one whose oil industry was considered one of the most efficient in the world, into a war economy, and achieved an equalization of misery, using the control of hunger and terror as weapons of social dominance.

While launching international campaigns to sell the wonderful utopia of “21st Century Socialism,” we Venezuelans die of poverty and famine.

At last, I have arrived at my job. The everyday job, the one that pays taxes, creates employment and whose productivity is seen in the results. The effort of private initiative, the only kind not stopped after the presidential decree, a decree that reduced the working hours of public employees to a half day, from 7:30 AM to 1:00 PM starting in late February this year, in order to address the energy disaster caused (for the second time) by the El Niño phenomenon, for which they never made provisions.

I am part of the private effort that continues to work a full day and that doesn’t shorten the workweek to two half-days, which the parasitic government decreed at the end of April this year, with its announcement that public employees would work only on Mondays and Tuesdays.

I’m part of one of the lowest classes in “21st Century Socialism.”

The society is divided into two blocks, consisting of castes:

Those Above:

Bolibourgeois: The highest framework of political, economic and military power, privileged and amalgamated under a corrupt system in which one has to have to have “wet hands” to belong and not represent a danger to the rest. For them there is no humanitarian crisis nor shortages and they are the ones who do not understand why those below “don’t eat cake, when there is no bread.”

Businessmen survivors: Simply entrepreneurs who are committed to working in Venezuela, whose lives abroad are assured, as are their possessions and in many cases their families. However, they are still here and on them depends a large number of direct and indirect jobs and they support virtually the entire weight of the low production and taxes.

Political opposition: Formed by the union of old and new leaderships, which are determined to return the democratic spirit of the nation through constitutional means. Enemies of the status quo, traitors to the “Bolivarian” ideal, political prisoners.

Those below:

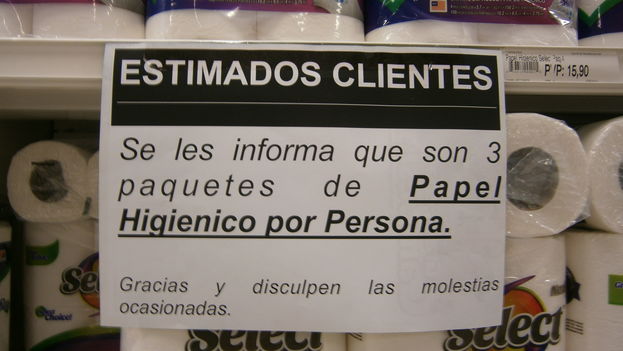

Public officials: Those whose activities cannot be cancelled. Important people in the areas of healthcare, control, repression or “protection.” They are the first to get food…

Public employees: Those employees whose activity can be cancelled without stopping the running of the country. I offer as proof, months of no activity and everything is working. They are second in line for food.

Elderly: Older adults, some pensioners, other survivors, must stand in line or they simply don’t eat.

Bachaqueros: (a word derived from bachaco, a voracious ant-like insect) A criminal class that plays on the hunger and health of its peers, new proprietors whose networks are fed by the bolibourgeois, the “connected,” the corrupt or the Local Committees of Supply and Production. I don’t know exactly where to put them because they move like mafiosos, in the shadows.

Paramilitaries and Colectivos: Criminal fiefdoms, charged with extrajudicial state security. Official paramilitaries susceptible to extermination when they try to take private initiatives. Generally, they are the best armed in the country. They gather in mega-bands with specific territories and strategic alliances.

Us: Those of us who continue to work every day, who sign, validate, provide the masses for the opposition marches, the nonconformists, those who have no time to stand in line because if we don’t work the country stops, the employees of small initiatives, small businesses and merchants, artisan producers, service-oriented microenterprises. Those of us who use the weekends to get whatever food we can find.

Others: Survivors, the needy, those who rise at midnight to get two bags of rice and two packages of flour, to feed seven or eight people, because they cannot afford produce, those who die of scarcities because they can’t get or can’t afford medicine. Those who die in a hospital for lack of a catheter. Those who stand in line with their children who no longer attend school because they can’t feed or clothe them properly. Those who go through the trash of the supermarkets looking for an onion or a tomato they can eat. Those who are angry because they feel cheated. Those tossed out of the public administration because they were denied their right to claim indemnization on penalty of losing their money forever, or who don’t have the power to work in a public institution. They were fired for signing petitions against the government or for having different political preferences, simply because being a public official or employee requires submission to the one-party government.

The Others are the growing rage of a society devoid of values. The Others are the silent society, the timebomb of a savage revolution, without ideology or principles. Because they are the ones with their education and their human condition snatched from them, the ones who fall back on their instincts, return to the jungle.

I should also mention, without downplaying their importance, those who left, escaped, found asylum, dreamers and hopers who survive, the majority, in a diaspora spread across the planet. They are the displaced, part of a refugee and nomadic humanity, so much in vogue these days.

And to think that the food and medicine that is still gotten and shared is produced by the surviving Businessmen and by Us.

I should also mention without downplaying Those, those who left, escaped, asylees, and hopeful dreamers, who survive, most in diasporas spread across the globe. They are displaced, part of a refugee and migratory humanity, so fashionable has set.

And to think, that food and medicines and still get spread, are produced and carried by survivors Company and Us.

Venezuela is more than this. We Venezuelans must be more than this. But the mass seems to prefer eating crumbs forever, rather than rising up and changing, to make a change.