Like Gertrudis Gómez de Avellaneda (Camaguey, 1814-Madrid, 1873), the great poet, essayist and journalist Gaston Baquero Díaz (Banes, Holguin, 1918 – Madrid, 1997) moved between Cuba and Spain, where he went in March 1959, when the revolution toppled the social pyramid to which his talent had elevated him, despite poverty and racial prejudice. Unlike Madam Gertrudis, who triumphed in Spain and was then became known on the island, Gaston was a goldsmith of letters and a character in the press at the time he abandoned the tropics. For him, Spain was the great stage, the ultimate creative landing stage.

Gastón Baquero belonged to the Origins generation, centered around José Lezama Lima, Eliseo Diego, Fina García Marruz, Cintio Vitier, Gaztelu and other writers of memorable work, united by their creative diversity and art as an essential reason.He began its intense cultural activity in the thirties, despite graduating as an agronomist and sugar chemist. He wrote poems, articles, essays and translated authors from English and French, such as T. E. Eliot, P. Valery, H. Aldmgton and G. Santayana. His first poems and writings have appeared in Havana newspapers and magazines: Social, Verbum, Baraguá, Grafos, Espuela de Plata, Revista Cubana, Orbe, Clavileño, Poeta, América and the celebrated Origins. From 1945 he worked as Chief Editor of the Journal of the Navy, where he wrote the sections “Panorama” and “Compass Needle.”

The poems “Park” and “Dead Girl” announce his adolescent precocity, but the significance of Baquero begins with the poignant Words Written in the Sand for an Innocent (1942), although he had published decenas such as “Federico García Lorca” “Sonnets of Death“, “Song“, “Adam in Paradise” and others included by Cintio Vitier in Ten Cuban Poets (1948), which include “Prelude to a Mask,” “The Knight, the Devil and Death” and “Testament of the Fish,” well-regarded by the critics. And evoking this luminous stage, María Zambrano said, “that the sumptuous richness of life, the delusions of the substance are first that the void …” Hence, he highlighted in the intuitive and precocious poet the “sumptuous sensuality” of his poems.

Before these anthology texts Baquero released Poems of Another Time (1937-1944), including “Sing the Lark at Heaven’s Door“, “Cassandra” and some which were not reissued; they remain bright and airy creations, which will diminish with his entry into professional journalism and public activities.

Gaston Baquero’s Spanish stage, marked by the industrious scriptural silence and some intellectual ostracism despite working at the Institute of Hispanic Culture and for Radio Exterior of Spain, he was prolific in journalism and literature. This period corresponds Poems Written in Spain (1960), Memorial of a Witness (1966), Spells and Investments (1984), Invisible Poems (1991), Autoanthology (1992), and the essays Hispanic Writers of Today (1961), The Development of Marxism in Latin America (1966), Dario, Cernuda and Other Poetic Themes (1969), Indians, Blacks and Whites in the Cauldron of America (1991), Approaching Dulce Maria Loynaz (1993), The Inexhaustible Source (1995) and two volumes of his poems and essays prepared by Alfonso Ortega Carmona and Alfredo Pérez Alencart and edited by the Hispanic Foundation.

His vast work is barely known in Cuba, where his name was removed from the publishing world for extra-literary reasons, until 1999 when Efraín Rodríguez Santana, who received a scholarship in Hispanic studies and gained the confidence of the author in Madrid, published the anthology Gastón Baquero The Sonorous Homeland of Fruit, which contains much of his verse, a Bibliography and an Appendix on his life and work, with texts by Eugenio Florit, Emilio Ballagas, Lezama Lima, Cintio Vitier, Fina García Marruz, Eliseo Diego , Francisco Brines, Jose Kozer, Pius E. Serrano, Felipe Lázaro and others.

The postmortem tribute brought young artists back to the great lyricist, described by Lezama Lima as a sonorous poet “with an incorruptible vocation,” living in “the house of poetry.” Other members of the Origins group shed light on the poet from Banes. To Cintio Vitier, “the mulatto with the face of an African prince,” was a “stunning island behind the fog”, who “oscillates between life and imagination, between emotion and invention, between poetry and the person.”

Critics and supporters of Gaston Baquero carved out the universal coordinates of his poems and literary reviews, which reflect his philosophical and aesthetic principles, marked by eloquence, conjurers of death, Catholicism as a vocation, fantasy and culture, and the premise of the poem as a legitimate character of poetic creation.

As Gaston noted that one should have the courage, at the end of the road, to keep two or three poems representative of the intention he had to write, I will say which I would choose as his fabulous legacy. For the reader, I am sure that the transcendent journey, the rescue of the city, and the poetic play with history, will encourage you to go in pursuit of his verses. My choices are these:

* Words Written in the Sand for the Innocent.

* Testament of the Fish.

* Brandenburg 1526

October 11, 2010

Jesus is Catholic by inheritance though he rarely goes to church; he knows the Bible, the rituals, the saints and collects stories and stamps and likes to gossip about the legends of St. Lazarus, the Virgin of Charity, the Virgin of Regla and other venerated Cuban saints.

Jesus is Catholic by inheritance though he rarely goes to church; he knows the Bible, the rituals, the saints and collects stories and stamps and likes to gossip about the legends of St. Lazarus, the Virgin of Charity, the Virgin of Regla and other venerated Cuban saints.

Since the last week of December, the Cuban news media turned the propaganda time chart on the 52nd anniversary of the Revolution, whose reviled founders stayed in power and in the disgust of the population, submerged in silence and the routine of a half-century of slogans and promises.

Since the last week of December, the Cuban news media turned the propaganda time chart on the 52nd anniversary of the Revolution, whose reviled founders stayed in power and in the disgust of the population, submerged in silence and the routine of a half-century of slogans and promises. To assault the barracks in the eastern zone of the country, the participants bought arms, practiced marksmanship in various places around Havana and crossed the island, besides risking the lives of people who were enjoying the Carnival in Santiago de Cuba, killing dozens of soldiers and exposing their own men. The failure complemented the adventure, but it is worth asking: What would have happened if they had taken it? If the idea was to climb the mountains, why didn’t they just do that?

To assault the barracks in the eastern zone of the country, the participants bought arms, practiced marksmanship in various places around Havana and crossed the island, besides risking the lives of people who were enjoying the Carnival in Santiago de Cuba, killing dozens of soldiers and exposing their own men. The failure complemented the adventure, but it is worth asking: What would have happened if they had taken it? If the idea was to climb the mountains, why didn’t they just do that? While the international press spreads the case of the American contractor Alan Gross, held prisoner on the island for supposed espionage, and lodged a year ago in a special room of a Havana military hospital, another US citizen survives in a wheelchair in the Combinado del Este prison in Havana. He is Chris Walter Johnson, he was taken prisoner at the Rancho Boyeros airport in August 2009 and tried on this past 26th of December 2010.

While the international press spreads the case of the American contractor Alan Gross, held prisoner on the island for supposed espionage, and lodged a year ago in a special room of a Havana military hospital, another US citizen survives in a wheelchair in the Combinado del Este prison in Havana. He is Chris Walter Johnson, he was taken prisoner at the Rancho Boyeros airport in August 2009 and tried on this past 26th of December 2010. Perhaps Chris may not be one of those thousands of patients who invent reasons to obtain prescriptions for marijuana in California, one of the 13 states in the American Union which is betting on the legalization of this recreational drug, which produces a state of relaxation and serves to treat glaucoma, diabetes, depression, multiple sclerosis, and chemotherapy side-effects among other things; but at the same time it is contraindicated for diverse conditions such as headache, chronic bronchitis, etc., which also produce lesions in memory. God willing you recuperate outside Combinado del Este. Happy 2011, Mister Chris.

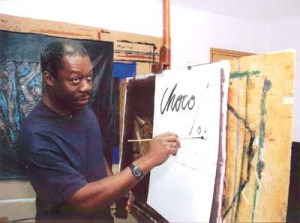

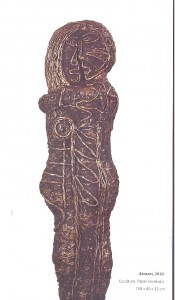

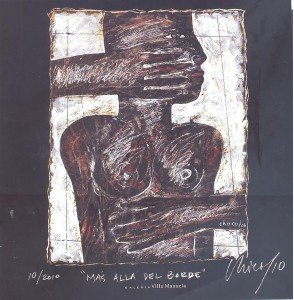

Perhaps Chris may not be one of those thousands of patients who invent reasons to obtain prescriptions for marijuana in California, one of the 13 states in the American Union which is betting on the legalization of this recreational drug, which produces a state of relaxation and serves to treat glaucoma, diabetes, depression, multiple sclerosis, and chemotherapy side-effects among other things; but at the same time it is contraindicated for diverse conditions such as headache, chronic bronchitis, etc., which also produce lesions in memory. God willing you recuperate outside Combinado del Este. Happy 2011, Mister Chris. The Villa Manuela Gallery extended until the end of November the exhibition Beyond the border, of the painter and engraver Eduardo Roca Salazar (Choco), who according to N. Echevarria, “returns to drawing and even makes a foray into three dimensionality through a set of “sculptured” figures, the inclusion of “Choir” (2010), anchored in earlier works, in which collagraphy forms a structural axis.”

The Villa Manuela Gallery extended until the end of November the exhibition Beyond the border, of the painter and engraver Eduardo Roca Salazar (Choco), who according to N. Echevarria, “returns to drawing and even makes a foray into three dimensionality through a set of “sculptured” figures, the inclusion of “Choir” (2010), anchored in earlier works, in which collagraphy forms a structural axis.”

An education system that instills loyalty to the leader, forces children to take an absurd oath and excludes from universities those who do not support their revolutionary pedigree, is like a barricade against intelligence, creativity and individual development.

An education system that instills loyalty to the leader, forces children to take an absurd oath and excludes from universities those who do not support their revolutionary pedigree, is like a barricade against intelligence, creativity and individual development. On Sunday morning November 21 you could hardly walk down Galiano Street in Central Havana, as expectation reigned in front of the American Theatre, home of musical and comedic performances, now converted into a Coliseum of muscles by the Cuban Association of Bodybuilding, which held its gala Challenge of Champions, broadcast on the sports channel of national television, something unusual since athletes who cultivate the aesthetic of the body are not yet officially recognized.

On Sunday morning November 21 you could hardly walk down Galiano Street in Central Havana, as expectation reigned in front of the American Theatre, home of musical and comedic performances, now converted into a Coliseum of muscles by the Cuban Association of Bodybuilding, which held its gala Challenge of Champions, broadcast on the sports channel of national television, something unusual since athletes who cultivate the aesthetic of the body are not yet officially recognized. The Journal of the International Festival of New Latin American Cinema is already out with its XXXII edition with previews the festival scheduled from December 2-12. Playing in the main theaters of Havana, home since 1978 to one of the most comprehensive festivals of images and sound on the continent; it includes the U.S. and Canada with co-productions, representative samples, conferences and the section “Latinos in the USA,” to which this year is added the Homage of the National Film Board of Canada, which is showing 47 works at the festival including animated, fiction, and documentary films.

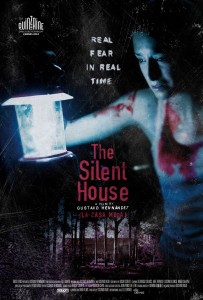

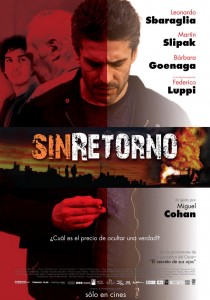

The Journal of the International Festival of New Latin American Cinema is already out with its XXXII edition with previews the festival scheduled from December 2-12. Playing in the main theaters of Havana, home since 1978 to one of the most comprehensive festivals of images and sound on the continent; it includes the U.S. and Canada with co-productions, representative samples, conferences and the section “Latinos in the USA,” to which this year is added the Homage of the National Film Board of Canada, which is showing 47 works at the festival including animated, fiction, and documentary films. Twenty-three first-run films are competing, led by Brazil and Mexico (4), followed by Argentina (3), Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba and Uruguay, each with two works. Generating the most interest are the entries from Argentina: The Intern, No Return and Puzzles; Five Favelas from Brazil; Of Love and Other Demons (Costa Rica) and Fierce Molinas and Affinities (Cuba), the second directed by actors Jorge Perugorria and Vladimir Cruz; and The Mute House, by Uruguayan filmmaker Gustavo Hernández, based on real events.

Twenty-three first-run films are competing, led by Brazil and Mexico (4), followed by Argentina (3), Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba and Uruguay, each with two works. Generating the most interest are the entries from Argentina: The Intern, No Return and Puzzles; Five Favelas from Brazil; Of Love and Other Demons (Costa Rica) and Fierce Molinas and Affinities (Cuba), the second directed by actors Jorge Perugorria and Vladimir Cruz; and The Mute House, by Uruguayan filmmaker Gustavo Hernández, based on real events. The Congress of the Cuban Communist Party, reorganized in 1965, and recognized in the Socialist Constitution of 1976 as “the highest leading force of society and the state,” continued to political orthodoxy outlined by Lenin, founder of the former Soviet Union, to which we tied ourselves for three decades. At the disappearance of this resources and guidance, the island ship was left to the mercy of the winds. The five-year cycle was interrupted; since 1990 the congress has been held or cancelled according to the convenience of the Castro brothers, party secretaries-in-chief.

The Congress of the Cuban Communist Party, reorganized in 1965, and recognized in the Socialist Constitution of 1976 as “the highest leading force of society and the state,” continued to political orthodoxy outlined by Lenin, founder of the former Soviet Union, to which we tied ourselves for three decades. At the disappearance of this resources and guidance, the island ship was left to the mercy of the winds. The five-year cycle was interrupted; since 1990 the congress has been held or cancelled according to the convenience of the Castro brothers, party secretaries-in-chief. Jose Maria Heredia (Santiago de Cuba 12/31/1803 – and Mexico 07/05/1839) is the first paradigm of Cuban poetry, despite being the son of a colonial official and living most of his short life outside the island, the center of his certainties, frustrations and hopes.

Jose Maria Heredia (Santiago de Cuba 12/31/1803 – and Mexico 07/05/1839) is the first paradigm of Cuban poetry, despite being the son of a colonial official and living most of his short life outside the island, the center of his certainties, frustrations and hopes. As a journalist for The Iris, The Conservative and other Mexican periodicals, he castigated the American colonists who demanded the annexation of territory to the United States, calling them “insolent usurpers” and “foreign vagabonds.” In his article Rumors of Invasion, which appeared on April 22, 1826, he called on his colleagues to “exchange the pen for the sword” against Fernando VII in order to liberate Mexico and other American nations from Spanish colonialism.

As a journalist for The Iris, The Conservative and other Mexican periodicals, he castigated the American colonists who demanded the annexation of territory to the United States, calling them “insolent usurpers” and “foreign vagabonds.” In his article Rumors of Invasion, which appeared on April 22, 1826, he called on his colleagues to “exchange the pen for the sword” against Fernando VII in order to liberate Mexico and other American nations from Spanish colonialism. This “air of light” shines in several of his compositions, almost always external and focused on the island drama, when freedom was envisioned only by pioneers such as himself and Father Feliz Varela.

This “air of light” shines in several of his compositions, almost always external and focused on the island drama, when freedom was envisioned only by pioneers such as himself and Father Feliz Varela. The Havana Ballet Festival, held from October 28 to November 7, and dedicated the Alicia Alonso’s 90th birthday, had moments of greatness with figures and groups from the island, North America and Europe, but it overemphasized the legend of the Prima Ballerina Assoluta, which distorts the situation of the National Ballet, marked by the exodus of its best dancers and choreographers, and by the aesthetic of classicism which distinguishes and limits its creative delivery.

The Havana Ballet Festival, held from October 28 to November 7, and dedicated the Alicia Alonso’s 90th birthday, had moments of greatness with figures and groups from the island, North America and Europe, but it overemphasized the legend of the Prima Ballerina Assoluta, which distorts the situation of the National Ballet, marked by the exodus of its best dancers and choreographers, and by the aesthetic of classicism which distinguishes and limits its creative delivery. To avoid offending Alonsova’s fans, I will refer to the honors received by the Diva during the 22nd International Ballet Festival of Havana, which drew companies from 18 nations, including: American Ballet Theater, the Royal Ballet of London and the English National Ballet, the ballets of the Operas of Berlin and Munich, the National Dance Company of Spain, the Malandain Biarritz Ballet, the Teresa Carreño Ballet Theater, Stars of New York City Ballet, and guest dancers such as Maruxa Salas and Vladimir Vasiliev, who gave Alicia the Galina Ulanova Foundation Prize of Russia.

To avoid offending Alonsova’s fans, I will refer to the honors received by the Diva during the 22nd International Ballet Festival of Havana, which drew companies from 18 nations, including: American Ballet Theater, the Royal Ballet of London and the English National Ballet, the ballets of the Operas of Berlin and Munich, the National Dance Company of Spain, the Malandain Biarritz Ballet, the Teresa Carreño Ballet Theater, Stars of New York City Ballet, and guest dancers such as Maruxa Salas and Vladimir Vasiliev, who gave Alicia the Galina Ulanova Foundation Prize of Russia. The Cinematheque and the Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry showed the films: Alice In Wonderland, made in 1962 by Pastor Vega; the short Spiral, by Miriam Talavera (1990), and Alicia, the Eternal Dancer, by Manuel Iglesias (1996); The Origins Gallery of the Great Theater of Havana, meanwhile, home to the Ballet and the Opera, presented the film Sleeping Beauty, with choreographic adaptation by the former ballerina.

The Cinematheque and the Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry showed the films: Alice In Wonderland, made in 1962 by Pastor Vega; the short Spiral, by Miriam Talavera (1990), and Alicia, the Eternal Dancer, by Manuel Iglesias (1996); The Origins Gallery of the Great Theater of Havana, meanwhile, home to the Ballet and the Opera, presented the film Sleeping Beauty, with choreographic adaptation by the former ballerina. Most passers-by hurrying between

Most passers-by hurrying between