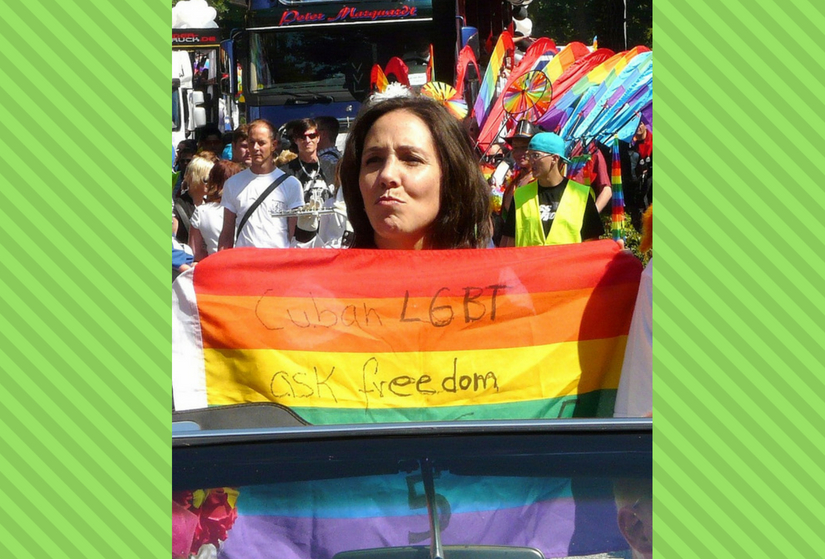

Tremenda Nota, Maykel González Vivero, 6 May 2020 — Mariela Castro Espín caused another controversy on Tuesday when, in deference to social distancing, she opened online the annual day against homophobia and transphobia organized since 2008 by the National Center for Sex Education (Cenesex).

During the transmission she made in the company of lawyer Manuel Vázquez Seijido and journalist Francisco Rodríguez Cruz, the LGBTI deputy, official and activist, took the opportunity to describe those who carry out activism outside of state institutions in Cuba as “tchotchkes” and “trivial ticks”.

In the tradition of the Cuban revolution, those who speak without official protection are disqualified for damages at the drop of a hat. For the militant anti-Castro regime, from the opposite bank, anyone who speaks from within the institutions is also disqualified.

continue reading

To avoid playing that game when dealing with Mariela Castro and for showing her how she deserves to be shown, it must be said that she has promoted LGBTI rights in all the instances she was able to exert influence and that she has fought for them in the Cuban parliament, away from any debate. She has earned the standing she has among international organizations promoting this agenda.

The legal, educational and health advisory services offered by Cenesex decisively favor the aspirations for the gay, lesbian and trans community in a country that has had more homophobic and transphobic policies than other western nation, particularly after the Cuban revolution.

For the LGBTI community, the work of that institution and the spaces for discussion it has fostered were a revolution. From afar and from other perspectives they have been described as “pink washing”. Here, Mariela has been perceived, day after day, by that charismatic leadership that she exercises in the tone of a “gay-like” woman, like an all-powerful fairy godmother.

Mariela’s name is a talisman for gay men arrested at rendezvous sites or for transgender women rejected when applying for a job. She is a “boss” who inspires her own scale of devotion similar to that which most Cubans bestowed on Fidel Castro.

That kind of cult is not healthy for the functioning of institutions, but it is accepted in Cuba and people justify it, without a doubt for lack of other experiences in political participation. I don’t know how she sees herself or if she questions that model during those times when she turns most revolutionary.

It may interest you: Nine controversial phrases by Mariela Castro

Cenesex and Mariela Castro did not contribute anything to LGBTI activism in terms of parallelism, transparency and coherence, a few of the conditions that the increasingly growing and ambitious movement demands.

The fact that a heterosexual and cisgender* person, not queer, nut or transvestite, is the best-known and authoritative activist in the country reveals the inconsistency on which official activism stands.

Mariela Castro also tends to present herself as an uncritical heir to a social project that excluded sexual dissent. When she has had to take sides, as happened in 2018, when Cuban politicians deleted the article on equal marriage and agreed to submit it for consultation within two years, she aligned herself with the official position and asked her followers to do the same, though doing so would be a betrayal of their beliefs.

There is a moment that seals the fate of Mariela Castro as an activist and leaves the official Mariela intact. That dilemma in which he lived for years was resolved on May 11th, 2019, the day that hundreds of LGBTI people and their allies marched through Havana to protest the cancellation of one of the street initiatives that Mariela herself promoted for a decade.

She had to speak on television and her official voice came out. She then stated, with her activist voice already discarded and without providing evidence, that the independent march was not legitimate, that it was paid for by the enemies of the government and that it does not deserve to appear, unlike what those who called it “the Cuban Stonewall” think, in the LGBTI memory of the island and the world.

Her attitude towards May 11th, the only one an official could have, eliminated Mariela’s prestige as an activist. The violent images that are engraved in everyone’s memory were the government’s response to LGBTI citizens.

Some of the “trivial ticks” alluded to yesterday had to go into exile after May 11th. Others remain in Cuba and strive to work independently despite the legal limits imposed by the government itself when it prevents them from legally associating and managing funds, as Cenesex does.

The metaphor of the “trivial ticks” brings to mind Mariela’s other controversial phrases with that same popular flavor and is very precise in this case. Out-of-control activists are “bugs that bite”. The deputy, intoxicated as she is from disobedient activism, wants to use an insecticide. May 11th ended with arrests. The plague is treated by spraying it.

Yesterday Mariela attributed a lack of “political culture” to independent LGBTI activism, but it should be read only as a lack of adherence to the authoritarian social project of the Communist Party of Cuba. These activists include liberals and supporters of US sanctions, but also anarchists, libertarian communists, and anti-capitalists.

It may interest you: Regulated: Mariela Castro and her family will not be able to travel to the United States

Mariela gives the traditional response that the political class used in Cuba to describe the conservative opposition, as if it had no other to give and would have been left without adequate words for the “Elvispreslians”, as Fidel used to say.

What does Mariela Castro have to say to those of us who disapprove of US interference in Cuban affairs and also reject the authoritarian style of the Cuban government?

This anachronistic response, this misunderstanding, as if her previous blunders and insulting metaphors were few, is more expensive than the silence before the “tchotchkes” that already marched through Havana, against tradition, without the White House and without the Revolution Square.

*cisgender: Latin-derived prefix “cis” meaning “on the same side,” also used as “cissexual,” refers to alignment of one’s gender identity and sex assigned at birth.

Maykel González Vivero: LGBTI journalist and activist. He had a blog while he was allowed, under the alias of El Nictálope, because he has always bragged of having good eyesight, like a nocturnal animal. He misses radio and the insomnia that helped him to write then. Now he writes when and where he can, collaborating with several Cuban and foreign media.

________________

A note from Translating Cuba: “It may interest you”… that this is our first translation from Tremenda Nota, an independent publication from Cuba, and we are hoping to do more!