![]() 14ymedio, Marcelo Hernández, Havana, 5 April 2018 — The official had a concerned look on his face upon seeing the two bags of salt that Laura Acuña was carrying in her suitcase on a flight from Bogota to Havana. “It was hard to explain to him why I was transporting two kilos of salt to an island,” recalls Acuña, a Cuban woman now living in Colombia, who was bringing it home to her mother.

14ymedio, Marcelo Hernández, Havana, 5 April 2018 — The official had a concerned look on his face upon seeing the two bags of salt that Laura Acuña was carrying in her suitcase on a flight from Bogota to Havana. “It was hard to explain to him why I was transporting two kilos of salt to an island,” recalls Acuña, a Cuban woman now living in Colombia, who was bringing it home to her mother.

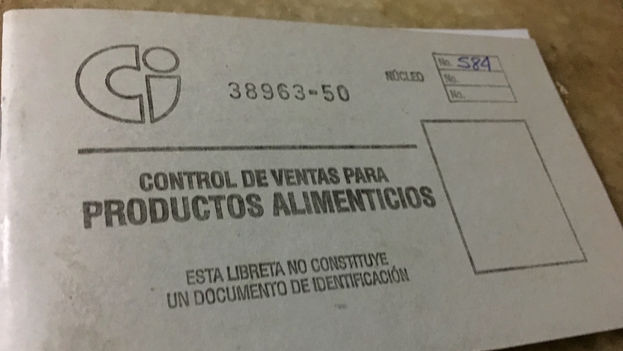

Since late last year it has been difficult to buy salt with Cuban pesos both in stores selling rationed goods as well those where products are not rationed. It is still available in hard currency stores but at a much higher price. continue reading

The black market is still an option but even informal retail networks have begun to see shortages. The situation has gotten worse with each passing week as shipments to government warehouses, where most of the merchandise is diverted to the illegal trade, fail to arrive.

Salt production has fallen in recent years according to the Statistical Annual of Cuba, published by the National Bureau of Statistics. Extraction of unrefined salt fell from a little more than 280,000 tons in 2011 to 248,000 in 2016. The official reasons for the decline have been weather-related problems and “technical obsolescence” within the industry.

The production of refined granulated salt, the kind used by consumers, has also fallen, from 93,700 tons in 2012 to 76,100 tons in 2016, according to the annual report.

Even with this fall in production, the industry should theoretically still be able to supply salt to the entire population. According to authorities, Cubans consume an average of ten grams of salt per day (twice the amount recommended by the World Health Organization), which translates into 40,800 tons per year. However, this 35,300-ton surplus somehow does not make it into stores.

“Every day people ask if I have salt but none has come into this store since January,” says Leandra, an employee of a small market on Havana’s Monte Street that distributes basic items. “We still have a little left but it’s quite damp. Other than that, it’s all gone.”

Of the island’s six salt processing plants, five are in operation and all are located in the central and eastern region of the country. Last September, Hurricane Irma seriously affected at least three of them, paralyzing production and leading to countless tons of lost production.

The director of Geominsal Business Group, Fabio Raimundo Paz, explained to the official press that the production areas that suffered the greatest damages were those of Puerto Padre in Las Tunas province, Santa Lucia in Camagüey and Bidos, located in the municipality of Martí in Matanzas.

All the salt that was still in drying beds and in so-called crystallizers was lost, while 5% of the product in storage and ready for distribution was damaged, according to the official. Weeks passed before the impact of these losses were felt on consumers’ dining tables.

Despite the fact that competent authorities have for months made assurances that “product availability” has been returned to normal levels and that the one-kilo bags “guaranteed” by the rationing system are being distributed, supplies of the condiment have become scarce.

Recently the local press Sancti Spíritus sounded the alarm, noting that since October, deliveries of salt to private sector stores — about fifty tons per month according to the weekly newpaper El Escambray — had been interrupted. Now “only those orders intended for basic rationing and certain of areas of public consumption have been delivered,” it added.

“Normally we don’t see much turnover of this product here,” an employee at a store in Plaza de Carlos III, the city’s main hard currency shopping center, explains to 14ymedio. “The people who buy this product here are almost always foreigners who are visiting the city or owners of privately owned restaurants,” he adds.

The employee has noticed a rise in demand for bags of salt, which go for 1.50 convertible pesos (twenty-five times more than the subsidized price of rationed salt). “They started buying it in large quantities and now we’re out of it,” he says. “Until recently the problem was toilet paper; now it’s salt’s turn.”

The response on the Ministry of Domestic Commerce’s hotline are terse. “We are waiting for additional supplies to arrive,” without any indication when that might be. In the manufacturing plants themselves complaints focus on a lack of organization and difficulties in getting the merchandise to the point of sale.

We are not tackling any number of problems, especially the issue of rail transport,” says an employee at El Real, a salt producer in Camagüey, who prefers to remain anonymous. The plant, which opened in 1919, has an annual production target of 20,000 tons. “Although the salt beds are well stocked, we lost part of the roof of the storage facility in the hurricane,” he adds.

“We are now in a race against time because, when the rainy season begins, which is normally in May, we have to halt almost all production,” adds the employee “When there is a lot of rain, the brine becomes contaminated with fresh water and dust,” he points out.

In the hotel and tourism sectors, the problem also creates a greater demand for food supplies, which creates additional stresses for some employees. “Until recently we were giving customers tiny doses of domestically produced salt,” says one of the waiters at the Hotel England, which faces Central Park.

“When we put out salt shakers, we had to keep an eye on them because people would empty them. We also have to add grains of rice to the shakers because it’s very humid,” he adds. “Before, we had to be careful that customers did not take the silverware or the glasses, but now we also have to watch out for the salt.”

_______________________

The 14ymedio team is committed to serious journalism that reflects the reality of deep Cuba. Thank you for joining us on this long road. We invite you to continue supporting us, but this time by becoming a member of 14ymedio. Together we can continue to transform journalism in Cuba.