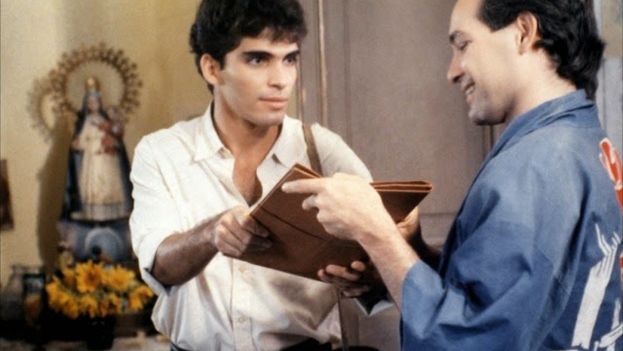

![]() 14ymedio, Luz Escobar, Havana, 2 April 2017 — Not even the most unconditional followers of Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, known as ‘Titón’, have seen the movie Strawberry and Chocolate as many times as Alberto Maceo. This Cuban with the mischievous smile worked as a projectionist at Havana’s Acapulco cinema when the film was on the marquee for a year. The movie left in indelible mark on his memory, which he still hasn’t been able, nor does he want to, get out of his mind.

14ymedio, Luz Escobar, Havana, 2 April 2017 — Not even the most unconditional followers of Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, known as ‘Titón’, have seen the movie Strawberry and Chocolate as many times as Alberto Maceo. This Cuban with the mischievous smile worked as a projectionist at Havana’s Acapulco cinema when the film was on the marquee for a year. The movie left in indelible mark on his memory, which he still hasn’t been able, nor does he want to, get out of his mind.

From Germany, where he currently lives, Maceo, ‘Albertico’ to his friends, learned last week that the only Cuban film that managed to sneak into the Oscar competition is going to be restored. The Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry (ICAIC) announced that it was a “very complex process,” despite the fact that the film is less than a quarter of a century old. continue reading

The news of the restoration unleashed a wave of nostalgia in the émigré. In 1993, when the story of Diego and David was released, Albertico was a teenager who no longer fit in his high school desk. Not only had he reached a physical height that made him stand out above his clasmates, but his restlessness pushed him into the theater. He played his first role in Pinocchio, while the movies allowed him to make a living.

It started as a lucky break to work as a projectionist in a difficult time when Cuban film production had plummeted and the projection rooms smelled of mold and sweat. In the midst of the Special Period, the young man began in a profession about which he recalls, “if you learn it well and focus on the details” you become aware that “what you have in your hands is a work of art.”

But enthusiasm wasn’t enough. Those were hard times, times when hunger and lack of sleep were not good allies in the projection booth. Albertico developed tricks so as not to fall asleep, from listening to music to reading a book, but few of them worked. He discovered that just talking with the other projectionists helped him manage to keep his eyes open while on the screen Titon’s movie played for the umpteenth time.

There were no lack of failures. One day when he was alone, sleep overcame him, and despite the cries of “done!” and “cut!” he only woke up when scrolling in front of the viewers’ eyes were “all those letters and numbers and marks at the end of the roll” that no one is ever supposed to see “in a good projection.”

“The only thing that really made our lives happy was the Film Festival every December,” he says now. It meant an oasis in the monotony of repetitive programming. “The bad thing was when the festival ended and the program was once again Strawberry and Chocolate ” he quips.

He came to know the film so well that a student asked him for a transcript of all the speeches of the characters and Albertico just needed to take a little breath to start repeating them one by one.

One day the young projectionist was transferred to the Riviera cinema, on 23rd street. He thought in this way he might save himself from watching the same movie every day, but his happiness was short lived. The National Film Distributor decided to schedule Strawberry and Chocolate at his new workplace as well. Albertico again had Titón’s famous work in his hands “like that brick Diego doesn’t know what to do with,” he jokes.

Among his most persistent memories is the music composed by José María Vitier for the film, although he remembers it in a rather peculiar way. “The material was pecked and scratched” so there were some notes of the credits that were missing. He got used to listening to it like that. Now, when he hears it in perfect quality his mind “always omits those notes.”

In those interminable replays trapped in an endless loop, from which he could not escape, he analyzed the movements of the actors, learned to know when they blinked, each one of their breaths and their pauses.” “Every frame” was recorded in his head.

Albertico began to detect those details which nobody noticed. “What does that actor do, out of focus there in the background? What happens to the strawberry in Diego’s spoon in the first scene in Coppelia?” He also began to notice those “microphones or cables that are accidentally seen in some scenes.”

“They are details that no one sees because Strawberry and Chocolate is a work of art that takes you along the paths of the forest,” he reflects.

“The funny thing is that in a year of screening, the film never failed to have an audience,” he recalls. “Those who had nothing else to do, who hadn’t seen it before, who came to smoke a joint, or the couple who would sit in the last row of the theater to eat each other alive,” and also those who “with Marilyn Solaya naked or a few seconds of sex on the screen, came to masturbate.”

He also recalls how the filmstrip fell apart in his hands because the material was in “very bad shape” and the projectionist comments that “in some cases you could see the gaps on the screen.”

Some time ago, Albertico bought a copy of Strawberry and Chocolate on DVD in a German market. Whenever he watches it on his TV he imagines the sounds of the roll in the projector. Although on the screen of his television the scenes shine, his eyes are enchanted to see the scars of that picture he had in his hands so many times.