![]() 14ymedio, Luz Escobar, Havana, 5 September 2017 — The young touchscreen generation looks at them with curiosity and the new rich keep their distance, but there are Cubans for whom public telephones continue to be an important way of communicating in the face of the high prices of the mobile service.

14ymedio, Luz Escobar, Havana, 5 September 2017 — The young touchscreen generation looks at them with curiosity and the new rich keep their distance, but there are Cubans for whom public telephones continue to be an important way of communicating in the face of the high prices of the mobile service.

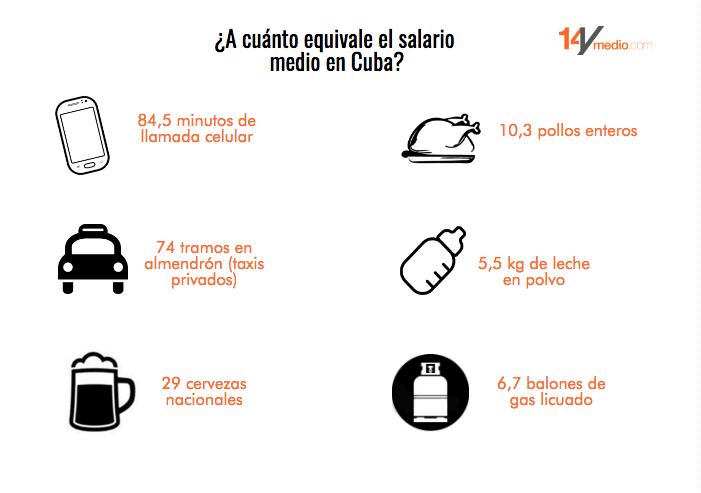

Making local calls from public phones is much easier on citizens’ pockets than using a cellphone. On the public phones, callers only have to pay 0.3 Cuban pesos (CUP) per minute during the day and 0.2 CUP per night (1.0 CUP = 4¢ US). For longer distance calls, such as between Havana and Santiago de Cuba, the price is set at 1.0 CUP during the day, 0.5 CUP at night, and after eleven PM it only costs 0.1, meaning a ten minute call can be made for the equivalent of just 4¢ USD. continue reading

In countries like France or England public telephones are on the verge of extinction, given the advance of cellular networks. In Spain, despite being a very deficient service and with an 84% decrease in available phones in the last 15 years (from 55,000 to 18,000 nationwide), the service is still required by law and the company with the concession was forced to renew its contract in 2017, when a public tender received no takers. As in Spain, the Cuban government is committed to maintaining, through the Telecommunications Company of Cuba (Etecsa), a service that is used by lower income citizens.

At the end of last year, the country operated 59,818 public phones, including 8,588 coin operated phones. For this year, the state communications monopoly plans to install 500 new public phones, of which 45 are intended especially for people with disabilities.

At the end of 2015, the country had only 1,333,034 fixed lines – in a country with over 11 million people – of which 996,063 served the residential sector, according to data from the Statistical Yearbook published by the National Office of Statistics and Information (ONEI). The installation of phone lines in homes has grown very slowly in recent years and between 2010 and 2015 just over 185,000 lines were added throughout the country.

Along with the poor quality of bread and the transportation problems, the problems with public phone service dominate the criticisms most heard on the streets and raised in the local People’s Power Accountability Meetings, where people can sound off to their elected officials. Deterioration, vandalism and the scarcity of phones in heavily populated areas are the subject of complaints.

Raquel Stone, a commercial specialist for ETECSA’s Public Telephone Services Division, told the official media that every year the company must repair thousands of public phones rendered unusable due to vandalism. The most common damage is having the handset pulled out.

Repairing the equipment represents an expense of 1,000 Cuban convertible pesos (CUC, 1 CUC = roughly 1 USD) for each coin-operated device, and between 330 and 400 CUC for each device that operates only with prepaid cards.

“The publics,” as they are popularly called, are in high demand not only among those who cannot afford a cell phone, but also among those who carry a cellphone so they can be reached, but make most outgoing calls from the devices located in the streets.

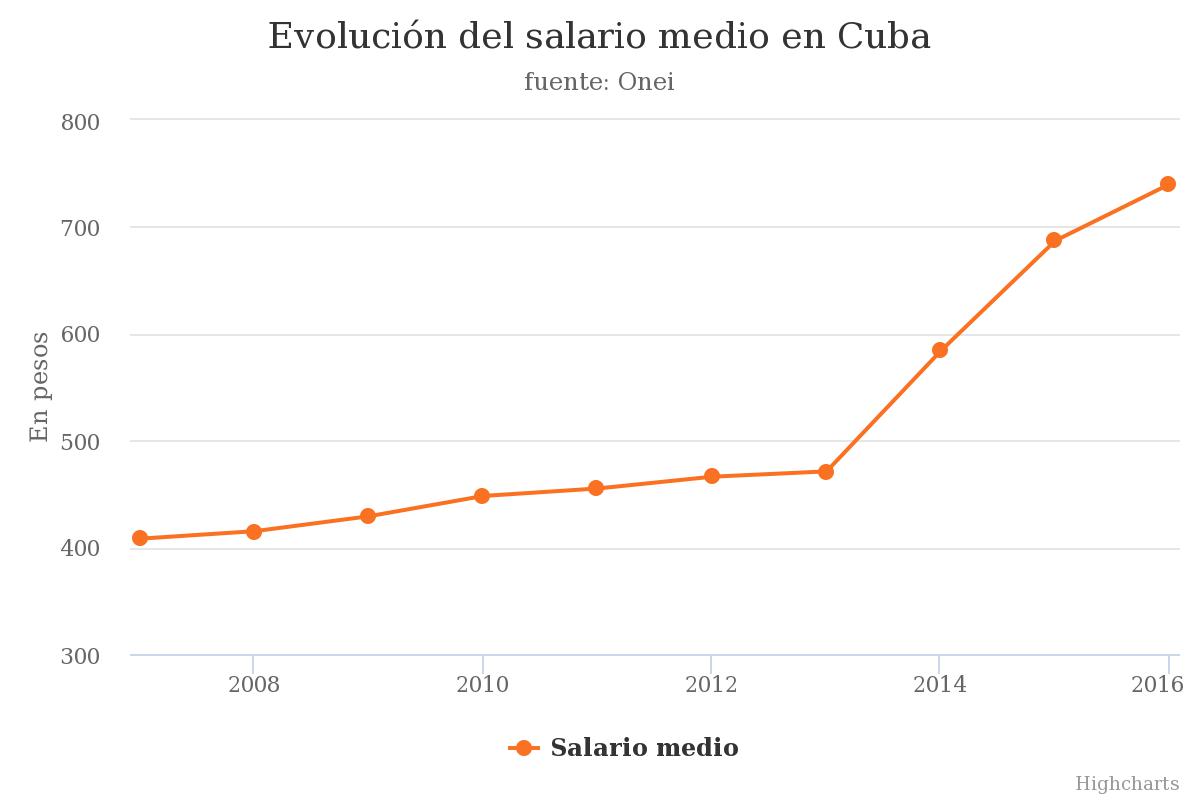

“If I call you and hang up on the second ring, it means I’m going to see you, but if I call you and let it ring, I can’t go,” a teenage girl shouts from the sidewalk to her friend who had just gotten on the bus. “But don’t pick up because I have almost nothing left on my cell,” she adds. The 0.35 CUC it costs for each minute of a cellphone call represents approximately half the daily salary of a professional.

In spite of these rates, in July of this year the number of active cellphone lines in the country reached 4,313,000. The growth experienced since Cubans were first authorized to contract for the service, in 2008, still places Cuba at the tail end of Latin American countries.

Only 35.5% of the Cuban population has access to cellular service, in contrast to nations such as Panama, where usage surpasses the number of inhabitants and is at the top of the region, with a 172% penetration rate for cellphone service. In Guatemala the rate is 115% and in Puerto Rico 88%.

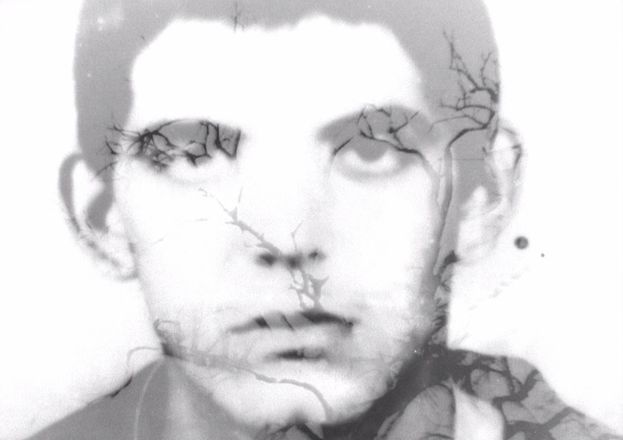

Aníbal Lorenzo, a 32-year-old pedicab driver who has been living in Havana for two months, is one of millions of Cubans who can not even dream of a cell phone. To maintain communication with his family in Guantánamo, he purchased a prepaid card that he uses on the public network. The worker laments that coin-operated phones almost never work.

“I have searched all the phones that are on Amistad Street,” he says while testing several unsuccessful phones. A few feet away, a young woman picks up a headset and hears the ringing tone, but before she starts to talk, she takes out a handkerchief from her purse and cleans the area near her mouth. “They are always dirty and stink,” she complains.

The telecommunications company has installed some public telephones in funeral homes, hospitals and pharmacies. The caller must dial 1-69-69 and charge the amount to the recipient of the call. The option is little known yet, but it can get one out of a bind.

“They stole my purse on the bus and a man told me that in a nearby Emergency Room there was a telephone that had that service,” says Rosaura, a young architect who before that incident not “touched a public phone for more than five years.” Now, she recognizes that in certain situations you have to go back to the old fashioned way.

In the last decade, attempts have been made internationally to offer new uses from public phone booths. In Spain for example, in addition to accepting payment by credit card, some have enabled the possibility of sending emails and SMS to mobile phones. Despite this, it has not been possible to avoid a fall off of 84% in this service in just 15 years.

In France phone booths have become public libraries in some localities, while in London the legendary red wooden cubicles are leased to small business owners who have turned them into small businesses, such as craft shops or tiny florists.

In the imposing building on the corner of Águila and Dragones streets, the ETECSA headquarters is located in a property that belonged to the American company AT&T more than five decades ago, when it was nationalized. In one of its rooms, a museum preserves several models of the first public telephones that were installed in the Island.

“All this is active thanks to a group of retirees who maintain the equipment,” says María del Carmen, one of the local workers. “In telecommunications schools, only new technology is taught now,” and these pensioners are “the only ones who have mastered these devices.”

A few yards from María del Carmen, a young woman receives a call on her cell phone while waiting to pay her telephone bill. She responds hurriedly and with short phrases. “Hang on, I’ll call you from an public phone,” she says as she looks around at the nearest devices.