The Cuban LGBTI community is celebrating this June 28, Gay Pride Day, inside. There will be nbo public march or rainbow flags on the facades of the institutions. With the unmet demands for marriage and adoption and the memories of the repression of May 11 still fresh, there is hardly anything to celebrate 50 years after the Stonewall riots that gave rise to the commemoration of this day all over the world.

René and Richard’s party will be attended by the latter’s parents and the sisters of both. René’s parents do not accept the union because they belong to one of the evangelical communities that most strongly opposed the inclusion in the Constitution of Article 68, which laid the foundations for equal marriage. “They almost have rejected me as a son and even if I could legally get married right now, nothing is going to change their reaction,” he laments. continue reading

In the neighborhood where they live and earn their living with a small hairdressing and massage business, many neighbors have accepted the situation but others do not speak to them, says Richard. “Although these are no longer like the times when there was even more rejection, we can not say that everything is a bed of roses. Sometimes someone insults me when I walk down the street and do not even think about walking hand in hand.”

Although Richard and René declare themselves “far removed from all the political wrangling” and do not engage in public LGBTI activism, they consider that from their place in society they are helping to move the wall of intolerance and rejection. “People have to understand that we are human beings and that we have the right to choose who we love,” one of them clarifies.

They have little confidence that the approval of a new Family Code, scheduled to happen in two years, contemplates the legalization of equal marriage and will give them full rights. Right now, if one of them has some mishap and dies, the other will not be able to get a widower’s pension and would not have the power to decide whether to bury or cremate his partner, should his family decides otherwise.

“Behind closed doors we are a couple like everyone else within the law, but as soon as we leave this house we are two people without any relationship before the law that rules the country,” René complains. “It’s like playing hide and seek, denying what everyone knows happens anyway,” he adds.

Yania, who asked that her name be changed for this report, drives a taxi leased from the State and has been with Leticia for seven years. Both are taking care of the latter’s son, the fruit of a previous relationship where abuse prevailed more than love. “We are two moms, although most of the neighbors think that I am her cousin and that I live with her to help her with the child, but they also gossip a lot about that,” she says.

Spending more than 14 hours a day behind the wheel, Yania supports her family while Leticia takes care of the child and domestic chores. At school, the taxi driver is called “Jeancarlos’s aunt” and the boy says “mama” only to his mother. He calls the other woman by a diminutive of her name. Both dream of being able to give him a little brother now that the family’s economic situation is better, thanks to the sale of a family home.

“We know we have no chance of being able to adopt a baby,” laments Yania. In the same block where she lives, a teenager from a family with problems of violence got pregnant and had proposed that they keep the baby. “But we do not want to do anything illegal, because tomorrow she will change her mind and we will not have any rights.”

In Cuba, the adoption of children by heterosexual couples is already complicated in itself. “If there are barely children available for adoption for heterosexual couples, who is going to open the possibility to homosexuals,” says an Education worker.

However, some have found ways to satisfy their desires for parenthood despite legal obstacles. “I grew up with two wonderful men and since I was little I knew they were a couple,” Liuba Herrera tells 14ymedio. Now a young college student, she was cared for from the time she was very small by two neighbors who lived next door to her house. “My biological mother was an alcoholic and ended up dying of cirrhosis of the liver.”

Carlos and Emmanuel, her two parents, took care of everything. “I had a childhood in which I did not lack anything, including love,” says Herrera. “At my school, some people made fun of me and made jokes in bad taste, but in the end they ended up accepting that I had two dads.” Now, their greatest dream is to become grandparents. “But they’ll have to wait because I’m still working toward graduation,” she says.

Today’s date, chosen in honor of the Stonewall riots (1969), has been extremely uncomfortable for the Plaza of the Revolution for decades, partly because the phenomenon originated in the United States in one of the moments of greatest rivalry between both governments. That aversion reached the point that the National Center for Sex Education (Cenesex), directed by Mariela Castro, opted to move the celebrations to the Day Against Homophobia, on May 17.

This year everything points to a stagnation for the LGBTI community in the struggle to conquer its rights. Ultimately, the article that would have opened the door to equal marriage was not included in the new Constitution, then came the cancellation of the conga celebration organized by the Cenesex and later the police violently arrested several activists who organized a march along the Paseo del Prado in Havana.

Despite having few reasons for the party, there are those who resist seeing this Friday as any other day, but little can be done in a country where free association does not exist and where many have preferred to live together as a couple, celebrating the day behind closed doors or raising a neighbor’s child because they can not adopt a baby.

“The ruling party has never taken the streets or celebrated this date. It has only been celebrated by the independent community, an example of that was the Gay Pride El Paseo that began in 2011,” gnacio Estrada tells 14ymedio. Estrada is, now a resident in Miami, was one of the organizers of that demonstration.

For the artist Adonis Milan, currently the greatest repression is “with the trans.” An LGBTI activist, Milan resides near Fraternity Park in Havana, a traditional meeting point for the community. “They [transsexuals] do not have jobs because they are not hired anywhere, so they live on prostitution, which is the only way they can sustain themselves,” he laments.

The police frequently raid the place, says Milan. “They arrive with a truck and take them away”, something that also happens in the vicinity of the Polivalente sports hall, another meeting place for transsexuals.

“They have already fined me three times and they fine me for male prostitution despite the fact that, in this case of meeting points, sex is for pleasure and not for money,” explains the artist. “The dynamics of the police is one of contempt and humiliation, but here there is no other place, the policy they follow with this community is hatred and contempt and they often mistreat us.”

The director of the Tremenda Nota magazine, Maykel González Vivero, does not believe that the repression of May 11 in the capital can be seen as a setback in the institutional attitude towards the community. “It is a position consistent with the official discourse, which has distrusted the rebellious nature of the LGBTI movement.” Remember that “Mariela [Castro] said that the so-called LGBTI Pride, the commemoration of Stonewall, is a commercial, capitalist party.”

For the journalist, “the closest thing to a Cuban Stonewall — people refused to accept the brakes applied by the authorities — was the march last 11 May, which Mariela rejected.” According to him, the Cuban authorities canceled the conga precisely because it coincided with a symbolic date, the 50th anniversary of the incidents in the New York bar. “In any case, the official notes do not lie, a disturbance was feared, which finally happened, something like a Stonewall.”

Although it is still a long time before Carlos and Emmanuel will be abvle to walk together as a couple with a grandson, the activist Isbel Diaz Torres, of the Rainbow Project, considers that “the Cuban Government’s policies of retreat on LGBTI rights have meant the perfect opportunity for an advance in the configuration of a true LGBTIQ movement on the Island.”

A few steps forward have been achieved “with autonomy and belligerence. No right is permanent or immovable, but we are learning that those obtained without struggle or social pressure, as benevolent gifts of power, are easier to lose than those conquered after a popular clamor, civic demands, the legitimate demands of the excluded.”

Torres points out that, after all, “to the Latin and African-American trans people of Stonewall, 50 years ago, nobody gave them anything.”

________________

The 14ymedio team is committed to serious journalism that reflects the reality of deep Cuba. Thank you for joining us on this long road. We invite you to continue supporting us, but this time by becoming a member of 14ymedio. Together we can continue to transform journalism in Cuba.

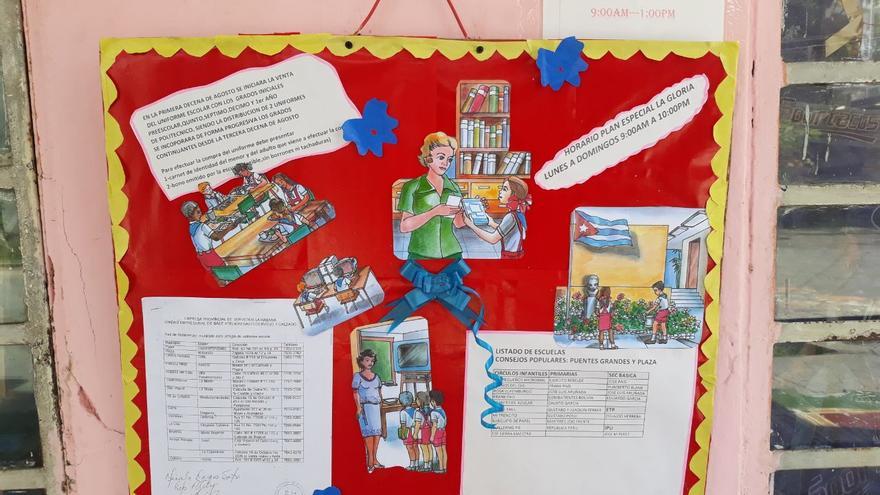

![]() 14ymedio, Luz Escobar, Havana, 26 July 2019 — Bulletin boards in schools or workplaces are often ornaments hung in a corner, loaded with historical events and photos that nobody pays attention to. However, at certain times they gain prominence and dozens of eyes gather around, such as when the date school uniforms will go on sale is posted, which sets off tensions, annoyance and hours of waiting for the families every year.

14ymedio, Luz Escobar, Havana, 26 July 2019 — Bulletin boards in schools or workplaces are often ornaments hung in a corner, loaded with historical events and photos that nobody pays attention to. However, at certain times they gain prominence and dozens of eyes gather around, such as when the date school uniforms will go on sale is posted, which sets off tensions, annoyance and hours of waiting for the families every year.