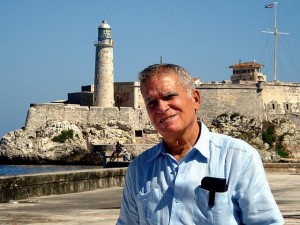

Surrounded by the books and periodicals that he treasured, he was now in the metal urn in the small apartment from which he’d left last March to seek medical treatment in Spain. For those who knew this couple it’s hard to imagine one without the other.

We went there in March and he died at the end of September. September 23. continue reading

Cubanet– Why didn’t you go earlier to improve his health?

Miriam Leiva – They wouldn’t allow him to go abroad and return. That is, we had to leave Cuba permanently. When he got out of prison in November 2004 he could have gone abraod and lived there permanently and gotten medical treatment, and he told me no, not without being able to return to Cuba, he wasn’t going anywhere.

Miriam Leiva – They wouldn’t allow him to go abroad and return. That is, we had to leave Cuba permanently. When he got out of prison in November 2004 he could have gone abraod and lived there permanently and gotten medical treatment, and he told me no, not without being able to return to Cuba, he wasn’t going anywhere.

Cubanet– What other limitations were imposed on his life on parole.

Miriam Leiva – When he was released in 2004, he comes to the house. Then they tell him he can’t return to his activities, he can’t write, he can’t speak. I alerted the foreign press that Oscar was here and they all came, everyone who wanted to, tons of correspondents accredited in Havana, and he immediately began writing and speaking.

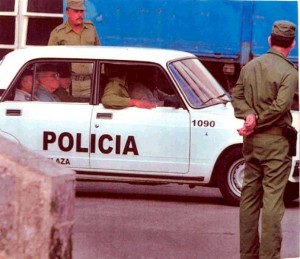

In a year and a half they called him before the Playa Municipal Court and told him he could not continue the activities he was engaged in, that he was being monitored by the neighborhood “factors” (the Party, the Young Communist League, and the Committee for the Defense of the Revolution) who would report on his behavior.

On the basis of that they gave him a document with some 11 prohibition, among that that he couldn’t leave Havana without permission, he couldn’t engage in exchanges, could not work. All this was in the document, something like 10 or 11 prohibitions. And he continued to do exactly the same things because there is a reality which he expressed in his opinions in a constructive manner and for the betterment of our country, and as he and I have always told them: prove that we are lying. Prove that we are saying something that is incorrect. They can’t prove it; we carry on.

Cubanet– And this year his health worsened?

Miriam Leiva – Last year in June he started to have a leg problem, with a lot of pain and then the problem in his liver started to get worse and he felt badly and lost weight. He was admitted to intensive care in Fajardo Hospital, which where he was always seen, and there they say that the biliary system was clogged, which seemed to have been going on for some time, and it was deteriorating.

The immediate solution was to put a prosthesis in the bile duct endoscopically, or minimally invasive. But this prosthesis lasted 2 or 3 months and had to be changed because it became contaminated by an infection in the bile processes, so they had to change it. He was admitted in December because it was going very badly and they told him they didn’t have an opening for him and he would have to wait until the beginning of January, it wasn’t the beginning it was the middle. But fine, they had an opening and the doctor he saw that time told me the problem wasn’t just an obstructed vile duct, but due to the deterioration of the bile system many of the branches of the ducts were badly damaged and that there was nothing they could do here. Perhaps abroad they would have other treatments but in Cuba there weren’t any more resources, no other possibilities.

Cubanet– And that time did they guarantee he could return?

Miriam Leiva – That was when we started to try to convince him to get treatment abroad because now, yes, if he remained in Cuba he would be dead sooner or later. And it was hard to convince him. Then he said, if they let me return I will go, and that mobilized me. I got in contact with different governments to see what the immediate possibilities were because somewhere else perhaps there was something they could do.

And the government of Spain — where they a lot of expertise in liver disease — said yes, they could offer medical care, but all the other costs would be up to us. And I didn’t ask how much the fare would be, but I said, yes, we will start the paperwork to get permission to leave and return. Here, we asked if he accepted a passport, could he return. Finally it was clear that he could return.

Cubanet– Tell us about Madrid…

Miriam Leiva – I was very afraid he wouldn’t make it to Madrid alive; but luckily he arrived. Very weak, but he got there. I got a travel helper and in the airport he went everywhere in a wheelchair. He didn’t have the strength to walk. We got there on Tuesday and on Wednesday in the morning we were at Hospital Puerta de Hierro. He went to the emergency room. They did everything, all the checks he needed to be admitted and when there was a room available, they took him there.

After some tests they changed the prosthesis. There they discovered that in addition to a diseased liver and the bile problems he had hepatitis B that hadn’t been diagnosed, and a bacterium called Clostridium. He was put in isolation because of the hepatitis. He was there for days while the hepatitis was treated and he was improved. They started a special treatment for the clostridium and he was better. But he was still feeling very very weak. He was hoping for a liver transplant, but given his age, over 70, they couldn’t do it. Besides he was very run down.

Cubanet– In Madrid there were the two professors…

Miriam Leiva – He gave a lecture at the Hispano-Cuban Foundation, which was his last recorded lecture. He had a very high fever that day. Afterwards, when Professor Carmelo-Mesa-Laga was there, he invited us to the hotel where he was staying. By email we told him it would be a huge effort for Oscar. Then Carmelo and his wife came to see us, we had already moved to a smaller and cheaper hostel. It wasn’t bad, I can’t fault the price.

Miriam Leiva – He gave a lecture at the Hispano-Cuban Foundation, which was his last recorded lecture. He had a very high fever that day. Afterwards, when Professor Carmelo-Mesa-Laga was there, he invited us to the hotel where he was staying. By email we told him it would be a huge effort for Oscar. Then Carmelo and his wife came to see us, we had already moved to a smaller and cheaper hostel. It wasn’t bad, I can’t fault the price.

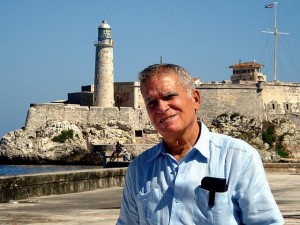

Carmelo invited us to go to his lecture at the Casa de America and another meeting at the Elcano Institute, a very prestigious Spanish institution in the area of Foreign Policy. It was nice because when Carmelo finished speaking in Casa de America, and other people were already asking questions, Oscar didn’t know that he was going to speak at Carmelo’s conference and asked a question. And before answering Carmelo said, “Oscar Espinosa Chepe, who is here.” It was very nice, he said some very nice words about Oscar and they applauded a great deak and that was a nice thing.

Miriam tells the story

Cubanet– Did his health worse in prison, in the Black Spring of 2003?

Miriam Leiva– After the search that begin in hour home at 4:30 in the afternoon and lasted until 3:00 in the morning they took Oscar to Villa Marista. A few days went by before they let me visit, maybe a week, I thought I would get a visit a week. It was a 15-minute visit with the officials in the little room and you couldn’t talk about anything other than family problems. He had already lost a lot of weight. He was sallow, a typical color when the liver is in crisis. Why? Because ot the intense interrogations in Villa Marista.

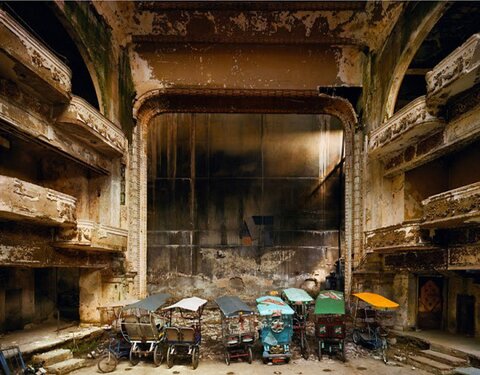

The Cuban government doesn’t torture in a way that is visible physically, but their psychological torture is suffocating and very intense. And this was what they did to Oscar. Then they simply put him in a cell with three common prisoners, and he could barely walk because it was very small, they had nothing there, no toothpaste, when he wanted something he had to bang on the metal for the jailer to come and open the bars and say “What do you want?”

The interrogators were there whenever it occurred to them, whenever they wanted, and especially when they thought he might be sleeping. So he wasn’t able tog et any rest. Oscar told me about the conversation, basically in his case, for example” how did he think, and why as he involved in this, why, it wasn’t worth it, that ultimately what was he talking about when he talked about reforms, he would give an example, “If even Vietnam and China are making changes and reforms, why can’t Cuba do it?”

The interrogator finally answered on the day of the trial, “Boy, because we’re not Chinese nor Vietnamese.” He continued to say the same things that he said here at home. The intensity of this system of interrogation and the bad food, the conditions, everything, what crowding there… he deteriorated a lot.

Because of our demands they took him to the Military Hospital. There they didn’t do any tests or anything, they told me that because he had been sent to prison he was going to prison. They sent him to the prison in Guantanamo. A journey very difficult for everyone, very hard, because they put them handcuffed in a bus, and they couldn’t talk to each other and they were left in all the prisons along the way until Guantanamo which was the last.

Cubanet– From Guantanamo he was taken….

Miriam Leiva – In Guantanamo he became very ill. I went there. Then they finally put him in the hospital of that city. It began to rain and the hospital only served emergencies, and they sent him to El Cobre Hospital, in Santiago de Cuba, that served the Boniato prison. There They wanted to do all the medical tests they thought necessary there and he said no. They told him if would have the tests they were going to take him to Boniatico, the isolation cells in Boniato. There were others of the 75 Black Spring prisoners in isolation cells there. Then I learned that he’d been sent to Boniatico.

Cubanet – What happened in Boniatico ?

Miriam Leiva – They dragged him off again to Santiago, with a doctor, from our family, and the prison director told me there weren’t any doctors, that I couldn’t talk to the doctors. I said, “Look, the only thing I have to do in my life is take care of Oscar Espinosa Chepe, and to I can stay here in the prison where I won’t bother you, but I will be there.”

Miriam Leiva – They dragged him off again to Santiago, with a doctor, from our family, and the prison director told me there weren’t any doctors, that I couldn’t talk to the doctors. I said, “Look, the only thing I have to do in my life is take care of Oscar Espinosa Chepe, and to I can stay here in the prison where I won’t bother you, but I will be there.”

Then an official from the Ministry of the Interior appeared and called him aside. This man never spoke the whole time, he simply sat there and when something in the conversation interested him he called an official from outside and told him what he had to do. Three doctors appeared, the head doctor and two others. We explained the whole situation, the doctor explained about Oscar. They went to see Oscar who was obviously very sick and they took him back to the prison part of the El Cobre hospital. They didn’t give him newspapers or anything, they put him in total isolation. They didn’t tell him we were there, that we came three times a day; his mother in the morning, his sister at noon and I at night. They completely isolated him.

Cubanet -From Boniatico to Habana…

Miriam Leiva — One day I learned that the afternoon before Oscar had been taken very ill about 3:00 in the afternoon and at the 11:00 PM they put him a plane for Havana and he was in the C.J. Finlay Military Hospital. This was in August 2003. I asked for a medical report. They said, “Yes, we will give it to you,” and they were going to do that when I met with a doctor in September, what they gave me was a piece of paper that didn’t say anything substantial. It was a tiny little medical history with less than I knew, much less. They didn’t tell my how Oscar was at that time, nor why he was there. You know they don’t give you medical information because they don’t want to. In March of the following year they gave me some information after a great deal of insistence on my part and also under pressure from the international community.

The psychological torture of Oscar Espinosa Chepe was intense, permanent, very malicious, everything. When the inmates were in the hospital they had one visit a week. Oscar had one visit a month and we never knew when it would be. It didn’t matter that I didn’t know, but he was the prisoner and he didn’t know. You know when Oscar found out? When they opened the cell. In this place the cells are rooms, it’s an old house with some little rooms. And he was with common prisoners, he knew Coco Fariñas was there for a time but he didn’t hear him, never saw him.

The prisoners had a right to television, but they never let Oscar see television. When he came from Santiago they took away everything, absolutely everything. They left him in Villa Marist and I I had to go to Villa Marista to find him. They even took his bible. The letters, photos, everything, everything, they took away everything.

On the first visit I showed up with a Bible and said, “Can’t Oscar have this here,” and so he had the Bible. He couldn’t have anything having to do with his life, with economics, with Cuba, with anything. They wanted to erase that man’s mind. They wouldn’t even give him the Granma newspaper. The only time they showed him television, they opened the curtain they had put across the bars of the cell and showed him the television from there — it was when the former foreign minister, Felipe Perez Roque said on TV that Oscar was lying about his illness.

Cubanet – Miriam, you were experiencing the punishment imposed by the regime on Oscar; but you continued writing…

Miriam Leiva – Yes, of course, I was writing more than ever. I didn’t stop. Then I was coordinating with the wives of the 75 Black Spring prisoners and we started a strong movement for their release.

Cubanet– Were you afraid at any point?

Miriam Leiva – Look, I’m going to tell you one thing: fear is felt for a moment sometimes, in certain situations. What happens is that you overcome the fear and it doesn’t overcome you. When it gets too much it gets on your nerves and you have to go or overcome it at home. And, well, all human beings are afraid… I think I’ve been very afraid at certain times, but it’s seconds and it passes and I continue on. You understand? The problem is overcoming the fear.

Do you know where I got my greatest strength? I can’t turn away from an injustice, they want to impose on me, they want to blackmail me, they want me to say things that aren’t true. And in addition, they are injuring a person who has done nothing wrong.

Cubanet – And now, what are the personal plans of Miriam Leiva?

Miriam Leiva – I will continue writing and expressing my opinion. My fundamental commitment was to bring Oscar’s ashes. It too two months to resolve the death certificate and to undergo my own medical check up, but I didn’t want to prolong it because I wanted to bring the ashes as soon as possible.

Lilianne Ruíz

26 December 2013, Cubanet

![]() 14ymedio, Havana, 2 August 2015 – This afternoon, after Sunday’s march of the Ladies in White on Fifth Avenue in Miramar, Havana, 40 members of this organization and about 15 activists were arrested.

14ymedio, Havana, 2 August 2015 – This afternoon, after Sunday’s march of the Ladies in White on Fifth Avenue in Miramar, Havana, 40 members of this organization and about 15 activists were arrested.