In the Havana of the ’80s, many of us young people were living without a future. Between guitar chords and conversations, at the foot of the bust of Jose Marti, at the entrance to the La Vibora Institute, we gathered at night to drink alcohol diluted with water, which cost 5 pesos a bottle from the house of a black woman, Giralda.

In the Havana of the ’80s, many of us young people were living without a future. Between guitar chords and conversations, at the foot of the bust of Jose Marti, at the entrance to the La Vibora Institute, we gathered at night to drink alcohol diluted with water, which cost 5 pesos a bottle from the house of a black woman, Giralda.

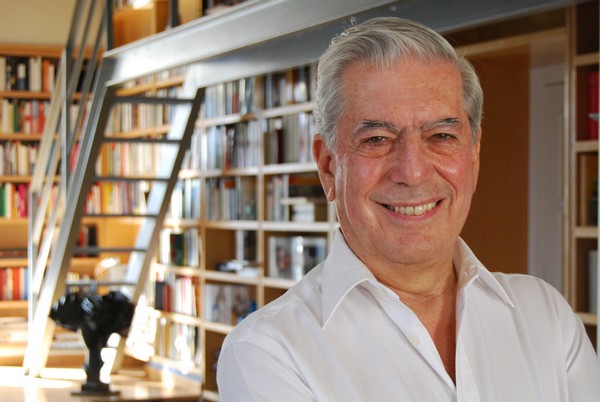

I took a blow. I don’t remember what the dissident picketing boys were protesting with a way of life that tried to turn us into Revolutionary leaders, but I borrowed a book by Mario Vargas Llosa, covered with a photo of Fidel Castro smoking a cigar and laughing like a hypocrite.

It was the City and the Dogs. At that time, so as not to attract attention, people used to cover the “banned” books with Revolutionary covers. I read it in one sitting. And now I confess I never gave it back. I was seduced by the Peruvian writer to the point that I have reread it at least ten times.

Later, when they threw me out of History class because I disagreed with the professor when he assured us that, for capitalism and the Americans, their days were numbered. I went to the school library. Hiding there, I read The Green House, published in 1965, the year I was born.

Nearly two decades later, one dark and warm night, I was going home when a police patrol, after searching me and checking my ID, with a big heavy Russian flashlight, reviewed in great detail the book I was carrying.

“Whose book is this,” asked the angry nervous officer. I thought of answering that he could see with his own eyes who the author was, but he was in a bad mood and I didn’t feel like sleeping in a cell at the police station that night.

“The author is a friend of the Revolution,” I lied. “He tells the story of an attack on Trujillo, the Dominican tyrant.” It was the Feast of the Goat. The cop looked me up and down disdainfully, and then threw open the door of his Russian Lada and told me, “Disappear mulato, the oven’s not for cupcakes.” It was March, 2003.

Eight years earlier, in 1995, I had started as an independent journalist at the Cuba Press agency. In this time I’ve had a number of inspirations. My mother, Tania Quintero, who gave me her love of journalism. Raul Rivero, poet and teacher of the craft, with his agile prose. Reinaldo Escobar, deep and analytical. Luis Cino, for his culture and mastery in Spanish. Claudia Cadelo and Laritza Diversent, two blogging lionesses.

But there are some special people who engage me to the point of delirium with the way they write.

At first, I tried to imitate them but over the years I learned that the bar had been set too high. Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Carlos Alberto Montaner are two of those. Mario Vargas Llosa is the other.

October 29, 2010

A couple of days ago I was walking with a friend to my daughter’s house and a cop car stopped us and asked for our IDs. Dog-faced like the usual Cuban police. They frisked us on the public street like common thieves. They wanted me to open an envelope with some magazines a Brazilian friend had sent me.

A couple of days ago I was walking with a friend to my daughter’s house and a cop car stopped us and asked for our IDs. Dog-faced like the usual Cuban police. They frisked us on the public street like common thieves. They wanted me to open an envelope with some magazines a Brazilian friend had sent me.

Communists or dissidents, famous or unknown, Cubans love awards and competitions. Of all kinds, national and foreign. They delight in being chosen and enjoy the glory they feel when they win.

Communists or dissidents, famous or unknown, Cubans love awards and competitions. Of all kinds, national and foreign. They delight in being chosen and enjoy the glory they feel when they win.

Forget the New Man Che Guevara dreamed of one day. We said goodbye long ago to that guy dressed in a uniform twelve hours a day and on the weekends we would prefer to read realistic Russian works like Volokolamsk Highway and How The Steel Was Tempered, before having a beer and listening to the geniuses from Liverpool. That New Man never put down roots in Cuba.

Forget the New Man Che Guevara dreamed of one day. We said goodbye long ago to that guy dressed in a uniform twelve hours a day and on the weekends we would prefer to read realistic Russian works like Volokolamsk Highway and How The Steel Was Tempered, before having a beer and listening to the geniuses from Liverpool. That New Man never put down roots in Cuba.