The Cuban revolution is a historic event. One cannot deny this fact. Its roots hail from this very country. It did not arrive as an import from the Kremlin. However, after perpetrating itself, in certain periods, it imitated the style found in Moscow.

The July 26th movement, headed by a young lawyer called Fidel Castro Ruz, the son of a Spanish soldier who fought in Cuba to stifle the independence movements of 1895, was not created in the disciplined ranks of the local communist party.

At first, he was a follower of Eduardo Chibas, a politician in the Orthodox Party, honorable, and honest. Castro was not a military or political genius. He was a Cuban who was, like many others, offended by the coup of Fulgencio Batista — a former shorthand sergeant who in the ’30’s was involved in the island’s politics and later in the ’40’s was president.

Fulgencio was from the same area as Fidel. Both were born in the province that is now known as Holguin, 800 kilometers from Havana. One was from Banes, and the other from Biran. After the hostility of 1952, Batista became the second dictator, after Gerardo Machado, to plague Cuba during the first 50 years of independence and republicanism.

What happened next we already know. A nearly suicidal assault on a military barracks in Santiago de Cuba (strongly criticized by the hierarchy of the national communist party, as they dubbed it a mini-bourgeois “putsch”); the guerrilla in the mountains, and the triumphant entrance of Castro and his rebel army to the Eastern city on January 1st, 1959.

At the moment, nothing indicated that Fidel Castro was a communist. You could tell Raul was, however. As well as his friend, the Argentine doctor Che Guevara. According to the guerrilla leader, his intention was to create a democratic government that would benefit all Cubans.

While in power, the revolution started radicalizing itself. Sometimes, in response to aggressive politics from Washington, and other times to consolidate its leadership. After two years of them declaring that it would be a “revolution greener than the palm trees”, we found out that it was more of an ideological red.

He started molding a Marxist country, designed similar to the vassal systems of Eastern Europe. Scholars of this subject nearly go mad and have written tons of articles trying to find out if Castro was always an all out communist or if he just used Marxism to rise to unlimited power.

I’m one of those who think the latter. Castro became an ally of Russia in order to keep himself at the head of the government. Fidel is Fidel. People with egos like his don’t follow a single ideology. They consider themselves to be above all those insignificances of thought.

He is an outstanding student of Machiavelli. His heroes are conquerors of the likes of Alexander the Great, Julius Cesar, and Napoleon. I’m one of those who believe that deep inside, Castro thinks that Cuba was too small for him. He wanted more. He would have wanted to be the leader of a world power. For the best, or for the worst, Fidel Castro was an important statesman of the XX century.

He was at the verge of provoking a nuclear massacre, and in addition, he had the carelessness to ask Khrushchev to fire the first atomic missile. Afterwards, he supported guerrilla movements throughout the entire planet.

One day, in the history books of the world, it will be written that a small, poor, and backwards country carried out military adventures in Angola and Ethiopia, nearly 10 thousand kilometers from its own coasts, moving over 300 thousand soldiers during 15 years of interventions in African civil wars.

Castro always loved conducting the theatre of military operations. In the decade of the ’80’s, from a mansion in the neighborhood of Nuevo Vedado, he frequently moved soldiers and tanks on a gigantic scale. He barked orders to his generals who sat in comfortable chairs in Havana.

He knew, inside out, the exact quantity of candies, chocolates, ice cream, and cans of sweets that the troops consumed. The One and Only Commander was never happier!

The old guerrilla fighter feels nostalgia over his command in La Plata and his marches through the Pico Turquino, in the Sierra Maestra mountains. Now, in the 21st century, while he waits for God to take him, his delirium has not ceased in the least bit.

All of his reflections have to do with international themes. What he’d give to be Obama, Ahmadinejad, Mahmud Abbas, Ehud Olmert, or Kim Jong II. He sees himself provoking and winning wars.

Only bureaucrats and functionaries can lead an economy or a state budget in an orderly way. The laws and the respect of norms of a party or institution are put in place so that common managers can fulfill them. Not for Fidel Castro.

Those banalities are handed over to his brother, Raul. The general is a practical guy. His dream is simple. That people be guaranteed their beans. And that the Cuban revolution last 100 years. It only lacks the second half.

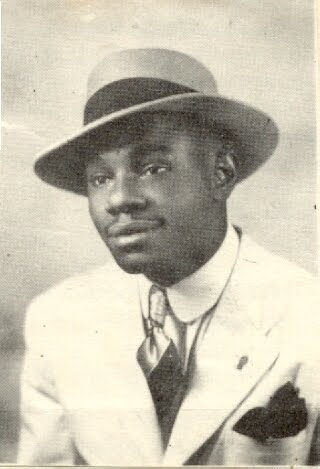

Photo: Grey Villet

Translated by Raul G.

December 31 2010

Eliseo, 39, is considered a public benefactor. A guy who is always welcome. For a decade, this Cuban American has been a ‘mule’. He resides in Miami and makes some fifteen trips to the island every year. Sometimes more. Right now, from his mobile phone, he calls his usual driver to pick him up at the entrance to the Jose Marti International Airport, south of Havana. He loads a bunch of bags and briefcases. He will be in Havana for one day. His mission is to unload the 150 pounds of food, medicine, electronics, clothing, shoes and toys, among other things, in a house that he trusts, where later they will take charge of delivering them to their destinations.

Eliseo, 39, is considered a public benefactor. A guy who is always welcome. For a decade, this Cuban American has been a ‘mule’. He resides in Miami and makes some fifteen trips to the island every year. Sometimes more. Right now, from his mobile phone, he calls his usual driver to pick him up at the entrance to the Jose Marti International Airport, south of Havana. He loads a bunch of bags and briefcases. He will be in Havana for one day. His mission is to unload the 150 pounds of food, medicine, electronics, clothing, shoes and toys, among other things, in a house that he trusts, where later they will take charge of delivering them to their destinations.