![]() 14ymedio, Caridad Cruz/Mario Penton, Cienfuegos/Miami, 17 April 2017 – teaching children cursive writing and educating them is much more than a job for Adrian, an elementary school teacher in Ciego de Avila. His threadbare pants stained with chalk dust make clear that he is not one of those most favored by the economic changes on the island, even with the recent 200 Cuban peso (about $8 US) raise in his monthly salary, which he received for teaching 27 third graders, more than the state class size norms.

14ymedio, Caridad Cruz/Mario Penton, Cienfuegos/Miami, 17 April 2017 – teaching children cursive writing and educating them is much more than a job for Adrian, an elementary school teacher in Ciego de Avila. His threadbare pants stained with chalk dust make clear that he is not one of those most favored by the economic changes on the island, even with the recent 200 Cuban peso (about $8 US) raise in his monthly salary, which he received for teaching 27 third graders, more than the state class size norms.

In January, Ministry of Education Resolution 31 decreed a selective salary increase of between 200 and 250 Cuban pesos for those teachers who have more students in their classrooms than the norms set for primary education. In the case of junior high and high schools, the teachers who teach more than one subject also receive a cash incentive.

“Money is not the main thing in life, rather it is fulfillment, and that is what my profession gives me,” says this 29-year-old “emergent” teacher, who graduated in the years in which the chronic absence of teachers made Fidel Castro launch his Battle of Ideas and graduate thousands of young people as teachers with just eight months of training.

At that time the hook used by the Government was exemption from compulsory military service and the possibility of getting a university degree in humanities without passing the qualifying exams.

Most of the young people who started the project left after the first years of work in one of the lowest paid professions in the country.

The damages to the quality of education caused by the lack of preparation of these emerging teachers remain to be measured, although with the arrival of Raúl Castro to the power in 2006, that program, like the other programs of the Battle of Ideas fell by the wayside.

“In January they raised the salary, but they do not want to call it a salary increase because it only affects those who have more than 25 children in the classroom, but at least it’s something,” he says.

At the beginning of the century, Cuba decided to limit class size to 20 students, but the chronic shortage of teachers and the exodus of professionals to other better paid work prevented this plan from being maintained.

“For years I did the same job and they did not pay me extra,” Adrian laments. “The workers union’s only purpose is to march on the first of May of the plaza. They never demand anything.”

Adrian has a salary of 570 pesos, about 23 dollars. He lives with his mother, a retired teacher of 68, and he is the family’s main support. His salary “is not enough,” he confesses, so he secretly sells treats among the students at recess.

“If it was not for that, I could not make ends meet,” he says. “After all, nobody can live on their salary in Cuba.”

The average salary of education professionals has hardly increased in recent years. In 2013 it was 512 pesos, two years later, 537 pesos

Teachers are not allowed to engage in business activities in schools, but many principals turn a blind eye to avoid losing the few experienced teachers they have left.

“They say that in some provinces, like Matanzas, the state sells food products to teachers at subsidized prices (above and beyond what is in the rationing system). If they did that, at least I would not have to sell candy,” he adds.

The average salary of education professionals has hardly increased in recent years. In 2013 it was 512 Cuban pesos, two years later, in 2015, official data confirm that the average wage is 537 pesos, the equivalent of about 21 Cuban convertible pesos (CUC) per month.

The current real wage, after deducting accumulated inflation, is equivalent to only 28% of the 1989 purchasing power, according to calculations by economist Carmelo Mesa-Lago.

Adrian’s mother, Elisa, recalls the years when she began as a “Makarenko” teacher (a collectivist method created by the Russian pedagogue of the same name) in the ’60s and says that the difficulties now are nothing compared to what her generation experienced.

“We earned 87 pesos a month and to be a teacher you had to climb Pico Turquino (the highest mountain in Cuba) and teach in very different places. There is nothing like teaching, it is teaching a person to fly. It’s the best profession in the world. If I were born again I would be a teacher again,” she says.

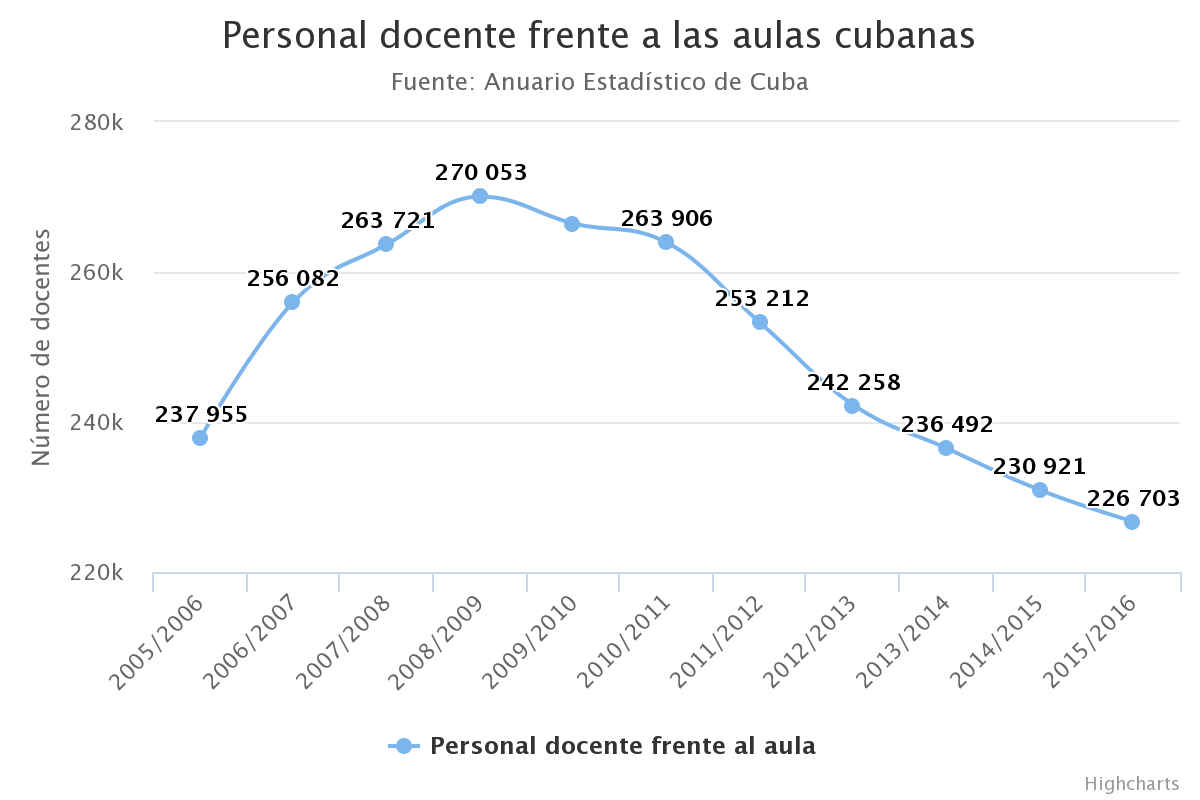

In the past academic year 2015-2016, there were 4,218 fewer teachers compared to the previous year. The trend has been accentuated since the 2008-2009 academic year in which official statistics begin to reflect the massive hemorrhaging of educators.

“Despite the salary of teachers and the conditions in which they perform their work, many remain in their posts. A driver in the city earns in one week what an education professional earns in a month,” says Elisa.

She receives a pension of 230 Cuban pesos a month, about 9 CUC. In the afternoons she has a small group of six children that she tutors for the price of 2 CUC per month each.

“I do it to help my son. We have to pay for the refrigerator, and life has become very expensive: a liter of oil costs almost a quarter of my retirement, and don’t even talk about the price of milk. Luckily I have an ulcer and they give me a ration of milk,” says the teacher.

Every afternoon Adrian collects the 27 notebooks of his students to review them carefully and correct the spelling mistakes. Jhonatán, “a javaito (Afro-Cuban) who escaped the devil,” helps him to carry them home.

“That nine-year-old boy’s mother was arrested because he was a jinetera (a prostitute). He lives with his father who is an alcoholic and who often beats him. The only signs of affection he receives are in school,” says Elisa.

“Being a teacher is not profitable but it teaches you to love,” the retired teacher says with emotion. “Sometimes Adriancito even buys the boy shoes because he has nothing to wear to school.”