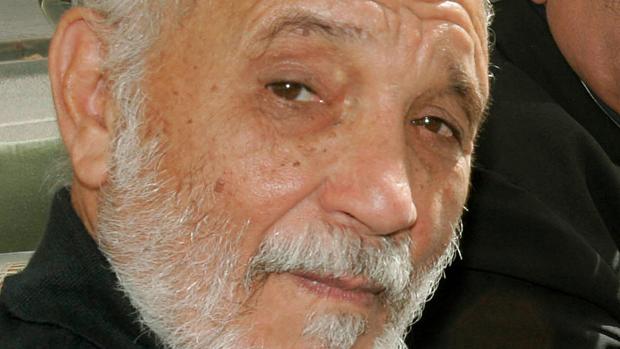

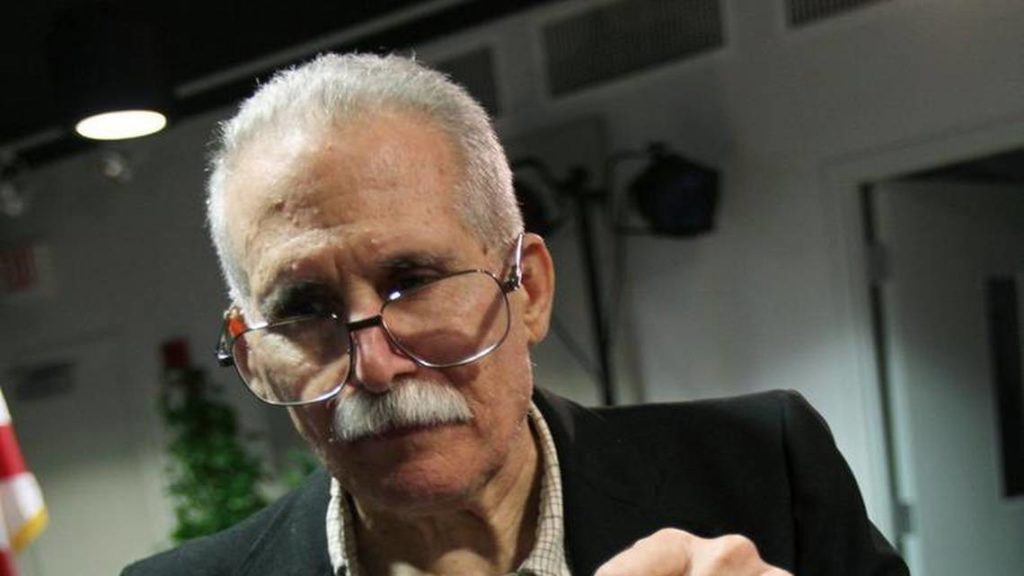

Cubanet, Luis Cino, Havana, 15 July 2019 — Despite my great admiration for him, I never thought I would write about Ricardo Bofill, who died this past 11 July. I thought that such a task would fall to, and be done much better by, those who knew him and were at his side during the hard years when the struggle for human rights in Cuba was begun. But I feel that there are things that should be said, and I don’t want to choke them back.

Cubanet, Luis Cino, Havana, 15 July 2019 — Despite my great admiration for him, I never thought I would write about Ricardo Bofill, who died this past 11 July. I thought that such a task would fall to, and be done much better by, those who knew him and were at his side during the hard years when the struggle for human rights in Cuba was begun. But I feel that there are things that should be said, and I don’t want to choke them back.

We in the opposition should take a lesson from Ricardo Bofill. In many respects, we should look to him as a role model.

With the creation in 1976 of the Cuban Committee for Human Rights while he was imprisoned at Combinado del Este, and later of the Pro Human Rights Party in 1988, Bofill was among the first to show that what up to that point had been unthinkable was actually possible: to deal with the Castro regime through peaceful means. Bofill and those who dared to follow him – Tania Díaz Castro, Reinaldo Bragado, Rolando Cartaya, Adolfo Rivero Caro, and others – who, for their recklessness were called crazy, proved that it could be done. Had it not been for them, the current pro-democracy opposition and independent journalism would not exist on the Island. continue reading

Thanks to Bofill and his partners, the world, which up to then had not listened – indeed had refused to listen – realized that in Cuba ruled a dictatorship that violated the most elementary human rights.

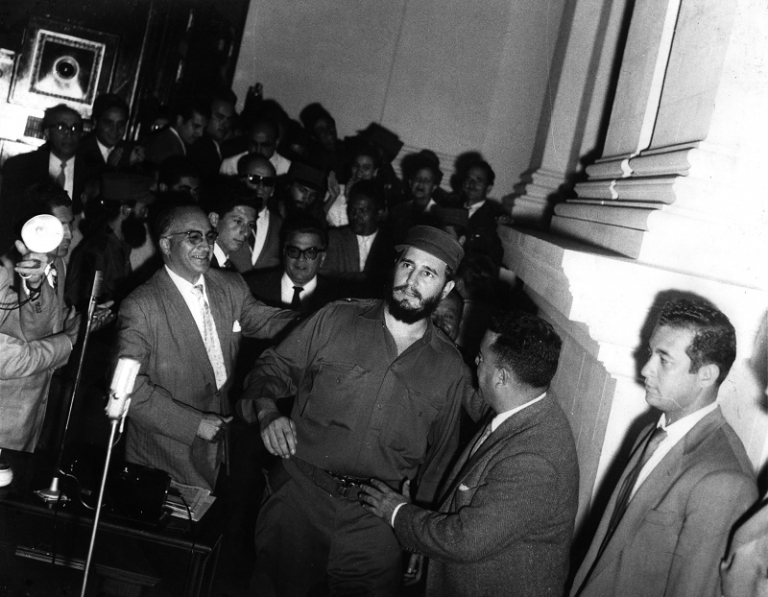

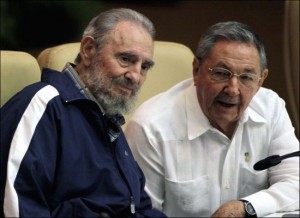

Said dictatorship, upon feeling challenged by Bofill, tried to crush him but was unsuccessful, despite devoting its most vile energies to the task. Imprisonment was not enough. Personal attacks by Fidel Castro (who denounced him as though to write against the Revolution were a terrible crime) were not enough. Neither were threats, character assassination, insults, Granma newspaper dubbing him “The Fraud,” – nor state-run television that reran to exhaustion that video edited by State Security which, to discredit him, cut and spliced it to take his words out of context so that Bofill would appear to be saying, “living off of this [dissent], man, living off of this…”

It was all counterproductive for the regime. The world understood what was going on and would never again view the Castro regime the same way.

That Bofill did not end his days in the regime’s dungeons was thanks to international pressure, particularly from the government of France.

In 1988, Bofill was able to travel to Germany. The regime forced him into exile upon not allowing him to return to his country.

They say that Bofill lived his last years in poor health, in poverty, in a humble house in a sketchy Miami neighborhood. Luckily, he was not without the company of Yolanda, his wife, ever faithful and unwavering.

Bofill, modest as he was (too much so), never sought honors or starring roles – and he had every right to do so. Certain dissidents who chase after recognition and renown even to the point of ruining the best project should learn from him and follow his example. I refer to those who refuse to sign a document if their signature is not at the top or if they disagree with even one comma, who think that they are always right and arrogantly view as enemies any who are not in total agreement with them.

We ought to be grateful to Bofill for the struggle that he initiated – but above all, for the example of virtue and dignity that he leaves to us. Hopefully, we will learn from it.

Translated by: Alicia Barraqué Ellison