The elderly are the big losers in the timid economic reforms of Cuba’s General-President. Thousands who once applauded Fidel Castro’s long speeches in the Plaza of the Revolution, or fought in the civil wars in Africa, today survive however they can.

There they are. Selling newspapers, peanuts, or single cigarettes. Others have it worse. Senile dementia has overtaken them and they beg for alms or dig through the dumpsters.

But even harder is life for an old dissident. Do the names Vladimiro Roca Antunez, Martha Beatriz Roque Cabello and Felix Bonne Carcassés mean nothing today? In the 90s they were the most active opponents betting on democracy and political and economic freedoms. In the summer of 1997 they drafted a lucid document titled “The Nation Belongs to Everyone.”

For this coherent and inclusive legacy they received verbal and physical violence on the part of the regime and its secret police. And they went to jail. Seventeen years after the launch of “The Nation Belongs to Everyone,” already old and with a litany of ailments, they are barely surviving. continue reading

Vladimiro, son of the Communist leader Blas Roca, had to sell his house in Neuvo Vedado. With the money he bought a crappy apartment and with the rest he survives. He’s about to turn 72, has never received the pension that he has a right to because he flew MIGs and worked in State institute.

Fidel Castro was implacable with the first waves of dissent. In addition to jailing them, he expelled them from the dignified and well-paid jobs And refused them a check on retirement. Others were forced to live in exile.

Bonne, the only black person in the group, was a university professor and prominent intellectual. He is almost blind and between the memory loss and shortages, waits for God to take him in his house in the Rio Verde neighborhood.

Martha Beatriz, a distinguished economist, is trying to weather the storm at the front of a network of social communicators, for which she receives insults and violence from State Security.

If the autocratic state doesn’t care about historical dissidents, who should watch over them? The younger dissidents? The current opponents should find ways to help the elderly dissidents.

It is just and humane. And is not acting like the government with the hundreds of thousands of men and women who, in their youth, didn’t hesitate to offer their energies and even their lived to his Revolution, and when they get old they are abandoned to their fate, with few exceptions.

To repair the unjust reality in the ranks of the dissidents, independent journalists Jose A. Fornaris and Odelin Alfonso are trying to do something. “We are working on how to create a support fund destined to the older opponents so they will receive at least 50 convertible pesos a month. Also this fund would cover a stipend for colleagues who are incapacitated by accident or illness,” said Fornaris, head of an association of free Cuban journalists.

For his part, Alfonso thinks that a kind of pension fund, “Every journalist who publishes his works and is paid, will voluntarily donate a portion. It’s sad how older dissidents are living.”

Implementing the project would allow dozens of opponents in their seventies to squeak by with dignity. Tania Diaz Castro, poet and journalist, was in the front lines in the hard years of the 1980s, when few dared to dissent against Castroism.

Their names should not be forgotten. Ricardo Bofill, Reinaldo Bragado, Rolando Cartaya and Marta Frayde, among others, gave birth to a party in favor of human rights.

Díaz Castro, a member of that party, never imagined that many years later Cuba would remain a totalitarian country. She lives in Santa Fe, to the west of Havana, surrounded by books and dogs. She survives writing reports for digital sites and with the dollars her children are able to send her from abroad.

And she is not the worst off. A few blocks from her home lives Manuel Gutierrez, in the opposition since the 1980s and founder of a dissident party. Now over 70, he earns a living working the land and tending goats.

He lives in a miserable hut of tiles and rough cement. But he does not complain. “That’s what happened to me. Worse off than me are the less known dissidents. It was my choice, to stay in Cuba and fight for change,” he said, trying to hide the tremor in his hands, due to unaddressed Alzheimer’s.

The current dissidence cannot and must not forget the past. When the current dissidents were afraid and silently accepted the regime’s public verbal lynchings of those brave opponents, they were speaking for all Cubans.

Now, we dissidents and independent journalists who don’t yet have grey hair, should concern ourselves with those who came before and opened the way for us. If the present is less repressive on the island, it’s precisely because of the old dissidents.

Iván García

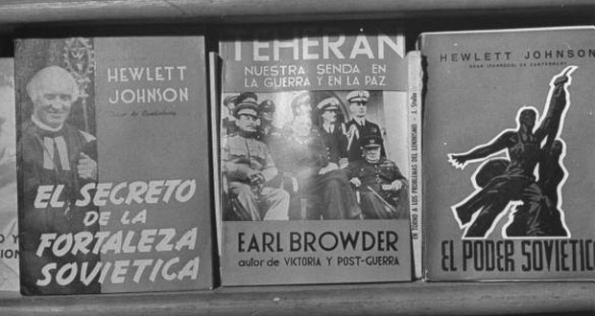

Photo: Gladys Linares Blanco, 72, a teacher by profession, is a prominent opponent who thanks to her conversion to an independent journalist, can more or less survive in Havana, where she lives. Another who survives thanks to his collaborations in digital media is the lawyer Rene Gomez Manzano, a former colleague of Felix Bonne Carcasses, Martha Beatriz Roque and Vladimiro Roca Antunez in the Working Group of the Internal Dissidence, the four writers of The Nation Belongs to Everyone. Unlike Gladys, René has been invited to events in the US and Spain, among other countries. The photo was taken from a Cuban Una cubana fuera de serie.

5 November 2014