There is a question I’ve formulated on more than on occasion, and that I have recently revived. It goes more or less like this: “If I, who detests with every particle of my being the North Korean dynasty, for example, suddenly gathered my intentions and provoked an attack that killed dozens of North Korean civilians, would this effort be enough to call myself, from now on and proudly, an anti-Kim fighter?”

There is a question I’ve formulated on more than on occasion, and that I have recently revived. It goes more or less like this: “If I, who detests with every particle of my being the North Korean dynasty, for example, suddenly gathered my intentions and provoked an attack that killed dozens of North Korean civilians, would this effort be enough to call myself, from now on and proudly, an anti-Kim fighter?”

And if, for example, my firecracker in Pyongyang causes collateral damage and sacrifices a European tourist, then can I call myself anti-dynastic, a fighter against Kim-the-father or Kim-the-son, and be treated like a hero, even though I haven’t touched a single petal on the iron dictatorship, which continues on its course without the least disturbance?

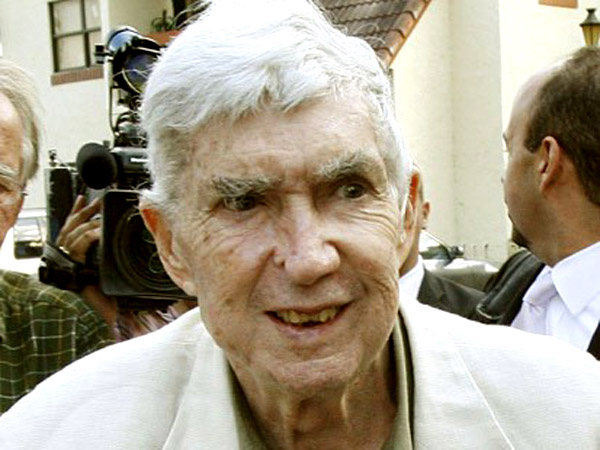

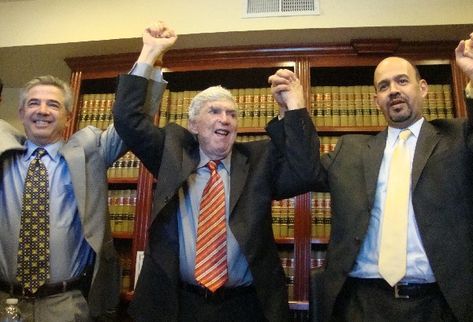

It’s something that’s returned to my mind now that Luis Posada Carriles is in the news again. For some, a hilarious story. For me, bitter news: I do not like his immediate and complete acquittal, I don’t like it at all, and I say this with the verticality of one who is not trained in the art of silencing what I think.

I have two reasons for not celebrating even one iota of this news. The first is: I don’t like this character. I could never sympathize with those who have death in their background, and who brag about it. Whatever its cause might be. And especially: whoever has the death of innocents in his background, poor unfortunates who were in the wrong hotel, or the wrong airplane, the day Luis Posada and friends decided to realize their “anti-Castroism” sui generis.

As a teenager I remember the long Cuban television broadcast dedicated to the bombings of 1997, the trial of Raul Ernesto Cruz Leon, the despondent face of an old Italian whose son, Fabio Di Celmo, was hit by a piece of glass that inevitably cut his jugular in the Copacabana Hotel.

And, since my untainted adolescence, I keep the memory of those days fresh: in the midst of devastating famine, in the midst of dissatisfaction and disgust for a country drowning in nothingness, a silence of anger and pain reigned everywhere.

The bombings of Havana hotels, the death of an innocent tourist, not only failed to topple the regime of Fidel Castro, not only did not precipitate the collapse of the Cuban Revolution, but rather it caused the opposite effect: in those hallucinatory days the Cuban people (even those who opposed the government publicly or privately), closed ranks with the establishment and approved almost anything they did.

The reason is very simple: Cuban society was hurt, its nerves were electrified. And where protection is sought in these cases, as always, is in the State. Let the Americans say otherwise: the country never vibrated with a greater sense of patriotism, never had a greater affinity with an administration, just as with Bush-the-son after losing three thousand and some lives in two New York towers.

But in 1976 I had not yet been born. I could not experience, as in 1997, the national horror. And it wasn’t just any kind of horror: it had to have been much worse than the one I did know. Between an Italian, a young man for whom he mourned, but, at the end of the day, a foreigner, and seventy-three Cubans, some of them teenagers, there is no comparison in pragmatic terms. I’ve seen the painful television accounts, but I have no life experience of it.

And still, I know perfectly well that any people who lose so many innocents, massacred by fanatics, irrational people who in their delirious warmongering are not capable of differentiating between a fighter jet and an airplanes filled with a beardless fencing team; I don’t have to have lived those days to know that Luis Posada and Orlando Bosch, not only are by their own confessions responsible for this crime (enough of tricks and rhetoric: have they confessed or not? Do we or do we not know that it was them?) They are, also, responsible for ensuring that a society in mourning gave more respect and power to a dictator who, in the future, would have more justifications, more scapegoats, to engage in his business of hijacking the national freedom.

But I have a second reason to find this news of Posada’s total acquittal bitter: the ugly scenario it presents to those who believe that the reconstruction of unity, of our history as a country torn apart, must start with a coming together between exiles and the Cubans over there.

How to convince those on the island, as a part of this second, that many of the stories offered on the Roundtable TV show, in the newspaper Granma, about the exiles of Miami, are nothing more that clever manipulations to further widen the breach that separates Cubans from here and from there? How to convince, for example, a Cuban of my generation, who grew up hearing the title os “Mafia terrorist of Miami,” that this demonization, that encompasses millions of exiled people, is only applicable to an ever-shrinking handful?

A single example: whenever I say publicly, here, that one of the strongest fears held by Cubans on the Island today is that, if there is a reconciliation between the two parties, the former owners will come and reclaim their old properties, dislodging people, displacing schools and clinics, many look at me with a smile of incredulity.

The truth is: I don’t know of a single octogenarian who left his home in Cuba, at the triumph of the Revolution, who still wishes to recover it. Not only because after so much time everyone has forgotten these losses — though not their resentment against the perpetrators — but because they know well the conditions in which they would find these old properties would require them to dynamite them and start from scratch.

But let no one doubt: is this one of the arguments most repeated by the regime. And what is its purpose? Well, very simple: to divide. To widen the gap between the two sides. To continue to stimulate the conflict and divert attention from a vital issue: the Cuban exile has nothing against Cuba, against Cubans, against that country that they love as few natives in the world love their countries. Cuban exiles, especially the historic generation, what they have declared war against is the government of the Castros, who know this very well.

But how do I explain this to my friends, as a solution to the strategic error so favored by the establishment, if suddenly a nation of eleven million people discovers that the alleged anti-Castro fighters do not kill tyrants but fencers in short pants?

How does one explain to the millions of Cuban television viewers that this beautiful march in support of the Ladies in White organized by two worthy siblings, true pride of our land, when the Roundtable simply put Luis Posada Carriles in the picture with them, neutralizing with a single image the message of peace and solidarity emanating from that initiative of the Estefans?

What Castro, member of the Castro family, friend of Castro or henchman of Castro, did those recalcitrant fighters kill with their attacks and their planes? I only know of one. One victim who feeds their egos. A solo victim to justify the title of heroes, if such a thing could be justifies, for example, as with those who shot the dictator Trujillo, in an act of death that would save so many lives.

But no. These gentleman who are honored and freed of any guilt, have only damaged one faction of this story: those who determine nothing. Big favor they have done to the cause of freedom.

I accept neither stories no half-measures: When, on April 8, the El Paso jury determined, in just three hours, that Luis Posada Carriles was innocent of everything, the strip of sea between Cubans of both sides grew thicker. And that, for those who have faith in a future where most exiles will not die without being able to visit the house where they were born, and where we will erase from our consciences — as the Germans have done — this shameful past of distance and pain, is a motive for indignation.

And, in my case, reason enough to write.

April 14 2011