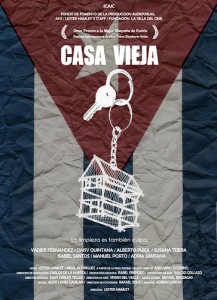

The fictional long-feature film Old House (Casa Vieja) has returned to the cinemas and to Screen #2 of La Infanta, where it can be enjoyed from 13-26 January by those who did not have the pleasure of watching it during the last Havana Film Festival, whose jury awarded it a Special Mention and the Popular Award, which lifted its maker’s Lester Hamlet’s ego; he expressed to Cacilia Crespo, journalist for The Film and Video Programme, that the re-writing of the play by Abelardo Estorino gave him the chance to speak from his essence and nationalism, to “narrate, from a human standpoint, a new conflict; to seek, to find, to suggest.”

The fictional long-feature film Old House (Casa Vieja) has returned to the cinemas and to Screen #2 of La Infanta, where it can be enjoyed from 13-26 January by those who did not have the pleasure of watching it during the last Havana Film Festival, whose jury awarded it a Special Mention and the Popular Award, which lifted its maker’s Lester Hamlet’s ego; he expressed to Cacilia Crespo, journalist for The Film and Video Programme, that the re-writing of the play by Abelardo Estorino gave him the chance to speak from his essence and nationalism, to “narrate, from a human standpoint, a new conflict; to seek, to find, to suggest.”

According to the filmmaker, his first work has found its natural niche within the present national film world, because it “speaks from the history of history and tells naked truths, undresses its fears with courage, and already participates in a conscious process of thousands of viewers who have welcomed it in their lives.” He adds that it is “a Cuban film made from patriotic pride.”

This defense is allowed but one needs not to exaggerate. Old House does not tackle any new conflict nor does it suggest anything extraordinary, even if it deals with enduring motivations of aesthetic resonance—cohabiting, sexuality and the existential trances of a family stuck in time—from a human angle. The family is stuck in the 90’s, but with a 60’s resonance in a run-down house where the patriarch is dying, an event that forces the youngest of his sons—a successful yet shy gay man who, without intending to, unties certain taboos and miseries sheltered by male chauvinism and social intolerance—to return home.

The melodramatic atmosphere of the household is one rooted in family values and traditions. A revolutionary past and the respect for established order—referenced by cyclones, armies, mobilizations and labor, as symbolized by the oldest son—palpitates within the home. The actor who plays this role is aging Alberto Pujol, whose character is a married man with children who works as the chauffeur for a town politician, and who despises the irreverent street-sweeper (Isabel Santos) who implores the recently arrived son to assist a young girl from the community who has been offered a scholarship abroad but has been denied an exit permit.

The rest of the film revolves around reminiscences of the mother (Adria Santana) and her other children (played by Yadier Fernández and Daysi Quintana), the brother of the dying man (Manuel Porto), some exterior shots of the coastal town, and funerary and burial scenes where some government secretary directs the acts and is interrupted by the main character, who hates hypocrisy.

The rest of the film revolves around reminiscences of the mother (Adria Santana) and her other children (played by Yadier Fernández and Daysi Quintana), the brother of the dying man (Manuel Porto), some exterior shots of the coastal town, and funerary and burial scenes where some government secretary directs the acts and is interrupted by the main character, who hates hypocrisy.

The contradictions in Old House are reduced to the distancing of the prodigal son—shy, cultured and mundane—from family masks and from the immobility of the townspeople, which is why, prior to his return to Spain, he tells his mother he only loves “living things that change.”

That’s where the “naked truths” and the “patriotic pride” end. There is nothing transcendental, neither in the acting performance of characters—limited by spaces and dialogs that were written for a different medium—nor in the geriatric atmosphere of stillness, poverty and lack of expectations. Perhaps the clue to the film needs to be looked for in the recreation of misery, the love frustrations of the marrying sister and in the untimely and honest street-sweeper played by Isabel Santos.

That’s where the “naked truths” and the “patriotic pride” end. There is nothing transcendental, neither in the acting performance of characters—limited by spaces and dialogs that were written for a different medium—nor in the geriatric atmosphere of stillness, poverty and lack of expectations. Perhaps the clue to the film needs to be looked for in the recreation of misery, the love frustrations of the marrying sister and in the untimely and honest street-sweeper played by Isabel Santos.

The reception of a work of art does not always confirm its worth or its contemporary character. Maybe hundreds of people witnessed their own secrets revealed by the characters of Old House, but the film seemed, to me, ambiguous and poor. The topic of the stigma of the homosexual in the family, the return of migrants who come back with a different perception, and the patriotic myth is well-digested bread in the island’s film milieu.

January 26 2011