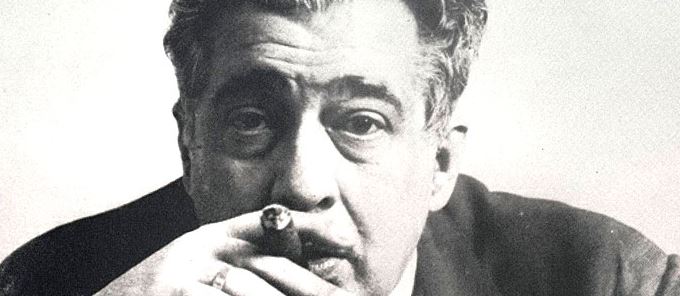

Luis Felipe Rojas, 9 August 2016 — He was the son of a colonel in the army, but was born to be the literary father to several generations. José Lezama Lima departed this life on 9 August 1976, and left a vast canon of work in which he wanted to embrace literary criticism, poetry, and narrative (stories and novels). The fat Lezama Lima continues to spell trouble for the Cuban government, because the much-vaunted post mortem promotion does not fit with the ostracism in which he was obliged to live the last ten years of his life.

With his novel Paradise and his posthumous book of poems Fragments to his Idol, he left tracks in both genres. The giants Julio Cortázar and Octavio Paz prologued (and possibly prolonged) both works and in each explanatory text they set out their admiration for the writer who had created a different subsoil.

Every type of literature has to be started by someone, a bricklayer who contributes to building the wall of the “great literary house.” Cuba had them in Villaverde and Martí, in Casal and La Avellaneda (Gertrudis Gómez de Avellaneda y Arteaga, 19th century Cuban-born writer). Lezama was a kind of restorer of that wall, on which we recline today to read a country. The Cuban narrative canon is made up of three fundamental novels: Carpentier, The Kingdom of this World, Cabrera Infante Three Trapped Tigers, and Lezama, with Paradise.

His poetic work is jumbled and inscrutable, based on insinuations and taking obscure liberties with good sense. Nevertheless it is in Fragmentos a su imán where Lezama seems to have taken a break from all his running about, and pushing to unsuspected limits the force of his literary searching.

The secrecy which he boasted of, including the evil they accused him of on many occasions, was left behind in Fragmentos …: “I am reducing, / I am a point which disappears and returns / I remain whole in the alcove. / / I make myself invisible / and on the other side I get back my body / swimming on a beach, / surrounded by graduates with snowy banners, /by mathematicians and ball players / describing a mamey ice cream.” (El Pabellón del Vacío).

He died alone, behind the backs of groups of intellectuals who attacked him when the Castro epic was started up as a new and highly polished epoch of an ancien regime, and decided to eliminate the bourgeois vestiges of the Republic. 1959 was the funeral of Lezema and of a literate republic. What came in the ’70’s was the opening and closing of the grave into which had fallen the intellectuals who had gone into obligatory exile or had stuck themselves in Cuba, never again to leave, as happened to Lezama; although the false recognition of the ’80’s had dazzled some and served for others to wash the vile hands of the censor.

Lezama raised himself with his own work, evaporated in the gossip of the island, which at that time was acclaimed as socialist and just, in order to make itself important and internationally recognised. His absence for years from national bookshops and the stupid limited space that Cuban universities now dedicate to him is an example of an official stoning.

To silence him is unforgivable. To lift him up as a false cultural policy is no more than throwing mud at his gravediggers. Long life, maestro.